a positive experience of success

making meaning

For twenty-five years I helped run a theater company. Our last performance was in May 2022. Since then, I’ve been cleaning out our storage unit and our offices and sorting through paperwork, dealing with residual finances, figuring out what to do with two decades’ worth of props and costumes and lighting equipment. It’s astonishing what you can find yourself in possession of, after twenty-five years of making theater. Swords. Steering wheels. A spectrum of police and court paraphernalia, testifying to the prominence in our society of criminal justice as an inspiration for drama.

And memorabilia: posters, cards, programs, photographs. As well as odder forms of memorabilia. The receipt from our first expense (priority mail postage to send articles of incorporation to the New York Secretary of State). The enrollment forms for some of my favorite kids. A note from a donor. All of it adding a layer of nostalgia to the physical labor - a layer of grief, really.

And I’ve been figuring out what to do with two decades’ worth of memories. Making theater always felt like writing in the sand; we would do a show, it would take over our lives for a month, we would strike immediately after the last performance. At the end of the night there was a bare stage and I wouldn’t be sure if any of that happened. So what do you have left then, other than photographs and posters and swords and a cardboard dragon? How do you grieve the loss of something that was so ephemeral to begin with?

I have heard that the final stage of grieving is “making meaning.” So I’m writing about some of what I learned in the last twenty-five years, as one attempt to make meaning out of all of it.

To start with, a moment that continued to frustrate me for years after it happened. Which seems overly negative, but another stage of grief is anger, of course, and the book says that the stages don’t happen in a good orderly fashion; sometimes they all come at once. And for that, a poet I once interviewed, Robert Hass, told me that all art comes from a place of resistance. I’m not sure if that’s true, but surely some art does. So here we go.

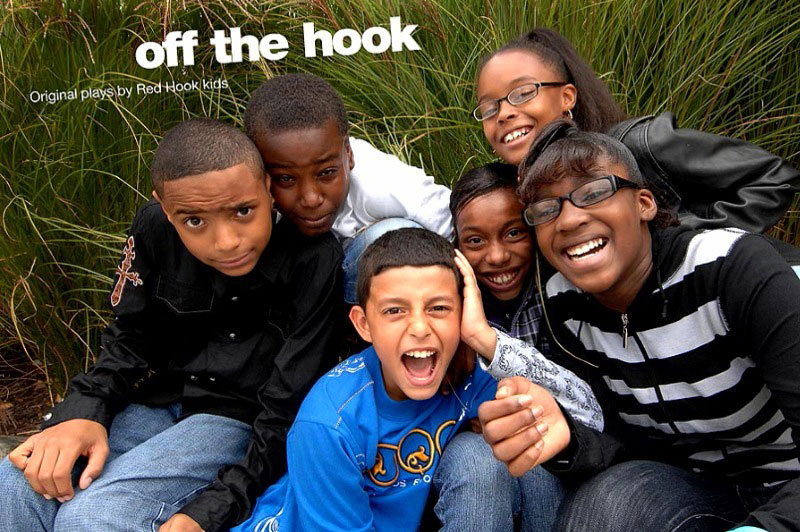

It was an evening one May, and we were preparing for the performances that culminated the cycle our “Off the Hook” program.

Off the Hook was a playwriting program for middle-school age young people. They would learn some basic techniques of playwriting in a weekly class, and then we took them on a playwriting field trip, and then we would produce their plays. It was, for better and worse, the cornerstone of our company. This particular spring, we had five kids who had written plays, which meant we had five separate companies rehearsing and needing costumes and props and sound effects and demanding time on the stage, all at the same time.

This was pretty normal in our seat-of-the-pants world. Off the Hook was ever and always a fiasco, until it wasn’t. Usually wasn’t happened on opening night. There was just too much to do, there were never enough people, there was never enough money; we were depending on volunteer actors and college students and underpaid tech people who might or might not be reliable; we were doing it in end-of-the-world Red Hook, where the B61 bus might take you twenty minutes or might take you an hour. It would be dress rehearsal, and an actor would be saying, “Where do I enter?” and the director would say “Upstage left” and I would say “We’ll have a door there tomorrow night.”

Occasionally, wasn’t happened on closing night. The aforementioned cardboard dragon made its one and only appearance in the second and final show of a kid’s play that Pink, our artistic director, had seen and decided needed a boost. She was right, the effect was magnificent, and among other things proved the ability of an audience to choose to believe. More on that some other time.

Anyhow, that was just the way we worked, because there wasn’t any other way, and because after a few years we got used to it and even liked it. We had actors and directors who knew how to roll with it - even thought it was a blast, like when they used to throw together a show in college. And we had some who couldn’t wait to tell us not to invite them back.

This particular spring, the one I mentioned above, we had a program director who I’ll call June. June was that theater person who could do everything you might need: direct a show, build set, sew costumes, write a song, find a weird prop, run lights, run concessions. After working as a teaching artist in city schools for fifteen years, June had seen and done it all.

What June was not was someone who wanted to roll with it the way we were used to doing after eighteen years of producing Off the Hook. That’s not a fault: it’s a style of working, and it can be a good one. If you’re teaching in the New York City schools, insisting on order is almost certainly the only way to keep disorder from devouring you. And even for a theater company like ours, it helped to have a person like that around to keep the trains running on time, or at least to make sure they aren’t heading toward each other on the same track.

In the context of the Falconworks Theater Company, however, it did lead to some culture clashes. Even that is not a fault. Years earlier we were doing a program called the Police-Teen Theater Project - another topic for another time - and I would meet regularly with a counterpart from the Red Hook Community Justice Center to work out the principles and logistics of the workshops. The Justice Center is a lot of things, but at its heart is a court, and courts like order - “order in the court” is literally something bailiffs say.

My counterpart Amy and I would disagree for two hours at a time, and then somehow - all of the credit goes to Amy - we would get to Yes, and I would realize that where we ended up was way better than what I had wanted going in. It led me to coin perhaps the corniest of the many corny aphorisms I coined while making theater, “Tension in the sail moves the boat forward.”

But however tidy a phrase you want use, that tension strains the various parts of the enterprise where they meet. In the face of June striving to achieve order, that spring’s production was a festival of disorder. We didn’t have costumes sorted before dress rehearsal. I was going home at night and jigsawing fake WWI rifles out of plywood. Our supposed technical director was a flake who would show up an hour late, or not at all, or would look at our antiquated lighting board with its analog dimmers and be mystified by his inability to program the thing, and further mystified by my explanation that you used all ten fingers, and a couple toes if you needed to, and played the thing like Van Cliburn going after Tchaikovsky’s First.

(You can be many things in the theater, but you can’t be a flake. This is something I’m not sure non-theater people get about the craft. You can have almost any number of personalities in any number of roles, but whatever role you’re in, you’d damn well better show up on time and ready to work.)

To summarize: an atmosphere of general chaos encompassing any number of instances of specific chaos. And June was going through it, and it one hundred percent did not help that I was not. She would find me and tell me about the problem du minute, and I would listen and say, “Huh. OK. We’ll work it out.” And go back to whatever problem du minute anterieur I had been working on.

The key to surviving all this was not to hold those problems too close. You keep a punch list, and when one of the kids’ directors comes to you and says, “We need a sound effect of a spaceship crash landing through a stained-glass window into a cathedral during evensong,” you write it down and say, “We’ll work on that.” And then you prioritize said punch list, and for some items you go back later and say, “We can’t do that, but -”

And that’s show biz.

One night after rehearsal we were leaving the performance space, a little stage in an art gallery. June was holding on to the problems of the day for dear life. I was gently trying to coax them out of her grasp. I wasn’t succeeding. I suspect, from her perspective, I was the one who wasn’t getting it: I wasn’t seeing that we were speeding toward opening night with no brakes and no steering wheel.

As we walked from the stage to our cars, I offered June encouragement, of the usual sort: you’re doing great work, the plays are awesome, everything is going to be fine. She had none of it. Possibly, the “you’re doing great work” bit may have enraged her a little, in that I suspect she knew she was doing great work; the problem was not her, but the obstacles our basket case of a theater company was throwing in her way. Anyway, it was pretty clear that “everything is going to be fine” wasn’t landing.

When I got home, I sent June a note:

I also want to say that there is one thing that matters in this, and that is that five young people have a positive experience of success. We all want to put on the best show we can, we want lights and costumes and sound to be right, we want the actors to remember their lines and not knock over the furniture. But in the end those things don’t matter; no one will remember if someone misses an entrance. What matters is that Jennifer, Erica, Stephan, Eddie, and Alexandra have a positive experience of success. Keep your focus on them and let the other stuff work itself out. We’ll figure out how to do lights, even if it’s lights up / lights down. We’ll figure out sound, even if it’s kids banging on tubs to make the sound of explosions. What matters is that five young people are going to take a bow at the end and come up taller, knowing what they have accomplished.

I freely confess to having stolen the “come up taller” line from Willie Reale, and I have zero shame about that. I thought it conveyed exactly what I needed to say.

The entirety of the message, however, was not exactly what June needed to hear. She replied:

Thank you for this...of course the kids feeling empowered is the whole point. I am very much trying to concentrate on that…. I can assure you that I will do everything in my power to have all of this be as much of a success as it can….

Since then, I have reflected on this exchange at length. What I came to realize was that June and I carried somewhat different definitions of “success” at that moment. With the benefit of hindsight - I think this is part of the grieving process, although I’m not sure which part - that’s a point of tension that we should have worked out on Day 1, as opposed to tech rehearsal. Maybe it’s an issue that should have been dealt with during a job interview. Or maybe it’s in the nature of a theater company - of any company, of any joint endeavor - that when a new person starts in a role, you say what you need to say, you go along to get along, and figure it’ll all work out somehow. By “you” I mean both parties, employer and employee, and I’ve been and done that in both positions. Sometimes it works out famously, and sometimes less.

Anyway, at that late stage I wasn’t thinking about the “how” of us finding ourselves with philosophical questions, and how we might have avoided that scenario. I was worried about getting a show up, I was worried about holding everything together, as a producer does. And for, in reality, the first time, I was pondering my pat phrase.

A positive experience of success.

I think it’s another phrase that got lifted from Willie Reale or his brainchild, the 52nd Street Project. I’m perfectly happy to have stolen from them. I’m less happy that stealing the phrase meant I didn’t have to do the heavier lifting of thinking about why it needed to be phrased that way.

A positive experience of success.

In truth, I had probably just thought the phrase was redundant, but flowed trippingly on the tongue. Aren’t all experiences of success positive by definition? To say I had assumed there was no such thing as a negative experience of success would suggest that I had ever put those words together in my head. With June’s response, suddenly that question was before me:

I can assure you that I will do everything in my power to have all of this be as much of a success as it can …

“As much of a success” for who? For you? me? the audience? How do you quantify success, in the way “as much” implies. Butts in seats? The number of curtain calls? The volume of applause?

Foundation people love asking the question “how do you measure success?” - it’s a standard question on every grant application. Trying to answer that led to one of the bigger fights I had with our artistic director Pink. There’s another post to come, to be titled “That’s not a Measurement,” which will address my evolving appreciation of what ought to be measured and what ought not.

That’s for another time, though. For now - or rather, for the day before our production - the question was, what constitutes “success”? And for whom?

The first place where June and I weren’t aligned was that in my heart I was never pursuing actual “success,” whatever that might have been.

(I will pause here to note that in the course of writing this post, I’ve realized how much I have thought of myself as not “me” but “us,” the company, the organization. And in truth, at that moment, I was the throughline and the steward of the company’s philosophy and values and traditions; I’d been producing Off the Hook shows for about fifteen years. Equally true, however, it was my interpretation of the philosophy, etc., that I was bringing to the theater that week. So I’ve revised some of the pronouns involved, and for the others you can do your own revising as it may make sense.)

Anyway, we - I - was never pursuing actual “success.” We - the company - were pursuing an experience of success, which existed not in the quality of the production or, mostly, in the way the audience responded, but in the minds and hearts of the young people who had written and were performing their plays.

I suppose it’s possible to achieve a kind of fraudulent experience of success - to believe you’ve achieved something when, in reality, what you believe you accomplished was in spite of lackluster effort, or thanks to the interventions of others. To have been born on third base, as the saying goes, and believe that you hit a triple. So there’s integrity in insisting that the success has to be authentic, that the plays actually had to be entertaining, polished, good - and not just in the minds of their creators. Indeed, a large segment of society fights the battle against this kind of fraudulent success, against the notion of a “participation trophy.” Maybe those folks have just taken up residence in my head, but I sometimes recoil against that idea, too.

But I don’t think that’s what we were working toward. To get to that bow at the end of their Off the Hook show, a young person had to grind through a lot of things. Weekly afterschool writing classes, when their friends were playing basketball or video games or watching whatever the internet algorithms were pushing. A host of exercises that depended on cooperation with other young people and adults. Working all day at a writing retreat (again, without basketball, Playstation, YouTube) in an unfamiliar place.

Handing off their work to a group of adults, including a director who was going to start making choices about what they meant and actors who were going to do weird and unexpected things. Learning how to stand their ground against that group of adults, how to work with them as a peer, and how to insist on their agency as an artist. Memorizing lines. And most critically, standing in front of a large group of strangers and owning all of it.

That ain’t “participation.” I am comfortable saying the kids’ experience of success was not fraudulent.

Apart from that, there’s the question Was this success worth it? And this is where that other word, the one that until that moment had seemed redundant, noses its way in: a positive experience of success. Because it is also possible, as I realized when we returned to the theater the day after my email exchange with June, and I started paying a different sort of attention to the rehearsal process, to have a negative experience of success - even a negative experience of authentic success.

At Falconworks we practiced a form of theater called “Theater of the Oppressed.” You can read a lot about it elsewhere, and I’m not going to try to say too much here, except to summarize one of its principles as - this will simplified to the point of being partly wrong - insisting on the agency and self-determination of every individual, including every actor in the company. I mean, yes, theater is collaborative and depends on cooperation; it helps greatly to be with people who show up on time and ready to work. But in T.O., everybody gets a voice and respect.

I think June hadn’t practiced that tradition the way that we had at Falconworks. She wasn’t unfamiliar with it; I recall discussing it during our interviews. But it hadn’t become part of her soul in quite the way it had for the rest of us who had been embracing it, or trying to, for at least a decade, or even the way it had for our core company members who might have been vaguely bored by it but knew how we worked and accepted it. I think the muscle memory June had developed tended to take her to a different place.

As I watched her work, following our email exchange, I recognized some instincts I had, and that I constantly struggled against - especially, a desire for our work and everyone involved in it to live up to some set of expectations.

Very little in life will lead to disappointment and frustration more certainly than insisting that children must live up to some predetermined set of expectations. I guess, sure, you can make them learn times tables or German conjugations or the form of the five-paragraph essay.

And, of course, Falconworks Theater Company brought a set of standards to the table. We wanted to do “good” work. At the same time, having expectations ran antithetical to our the principles. We lived forever in that tension; our work, over the long haul, for each of us as a company member, was learning to be more comfortable living in that tension. Allowing it to move the boat forward.

So we had expectations about the way people would engage with the process. You show up on time, ready to work. You treat people with respect. You say “yes” to ideas and see if they fly. And, sure, ideally you remember your lines and speak loud enough for people in the seats to hear you.

On the other hand, we did our best not to have expectations about what would come out of that process. “Some day,” Pink used to say, “a kid is going to write a play that’s one word long. And we’re going to produce it.” Any number of the kids’ efforts we produced failed to conform to the precepts of the well-made play. (In fact, the deeper we dove into Theater of the Oppressed, the less that became any sort of standard for us; if anything, the plays with messy and incomplete conclusions proved more interesting than the neat packages.)

As a matter of stagecraft, we did have moments when kids - or adults - forgot their lines. The number of sound effects that missed their cues probably outnumbered those that were timely. Our budget for scenery was forty cents. We ran shows with a complement of around twelve lights, which when fully engaged threatened to overload the stage’s circuit breakers at any moment.

In any endeavor, one begins with aspirations. And then one runs headlong into reality. The limits of our skills. The amount of time available. The tools at our disposal. We come into it with ideas about what good art is - good anything, but let’s stick with art for now - and constantly compromise between the good and the possible. Add to that that we were working in theater, which is meant to be collaborative - so now we’re compromising between our vision of the good and someone else’s vision, as well as the dimensions of their own possible - the limits of their own imagination and understanding of the world. Add to that that we were working with children.

It would be so easy, in these circumstances, just to insist on our own vision, our own way of doing things, because we think we know better. Or to take, or to give, shortcuts - Stand here. Say the line this way. Can we add a scene that explains this? - that bypass the artistic process. Worse, they short-circuit the developmental process - on the way to experiencing success, we encounter a lot of small (or large) failures, a lot of moments of discovering that we can’t do things the way we imagined, so we simply have to find a different way.

And worse still, those shortcuts abandon the very core of collaboration. They say to a child, I do not value your voice, your talent, your vision as much as mine. And so we either teach a child not to value their own voice, or we show them how not to respect others’. Fixing things - making a show be “as much of a success as it can” - implies a hierarchical way of approaching thinking and working and creating, in which some expert’s (some grown-up’s) vision and interests and knowledge and skills were the correct ones.

Finally, taking shortcuts to produce “good” theater undervalues imagination.

This is how schools operate. They drill times tables and conjugations; they force students into “success.” Undoubtedly, in part, my reaction to that modus operandi led me to abandon my own teaching career while it was still in the womb. From one perspective, schools need to work this way; one teacher can’t say “yes” to each of twenty-five students five times a day. But that was everything we were trying to deprogram.

And so, where I used the word “compromise” above - “compromise between the good and the possible”; “compromising between our vision of the good and someone else’s vision” - I was playing a trick on you. The very problem arises when we think of it as compromising. The very solution is to understand the artistic process - any process - from beginning to end, as embracing all of it, all of the limitations that each of us bring into creating art and centering the struggle to create, itself, as a thing of beauty and truth.

The negative experience of success subordinates all of these struggles, all the learning that comes out of them, to a finished product. The positive experience of success welcomes them as friends and allies.

As much time as I spent grappling with the implications of these questions, during eighteen years of producing children’s theater I only partly wrote any sort of analysis of them, the way I am doing now. We lived them more than articulating them. It gradually made its way into our muscle and bones. Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.

I am just trying this out right now; it might be entirely wrong. To test it I would need to go back and relive those eighteen years, asking myself if this is true. I think that would be a fool’s errand. I’m going to choose to believe I’m on to something:

Enlightenment occurs at that moment of “coming up taller” occurs when kids find themselves onstage with peers, those of their own age and those who are more experienced, and know: “I did this, and then we did this. I wrote a play, about things that were important to me, or interesting to me, or funny to me, and other people took it seriously and did their best to bring it to life.” Nobody told the kid the right way to do it - we just kind of invited them to go at it.

And that play didn’t achieve everything the kid wanted it to, because none of us can make a thing that is everything we want it to be, and the company’s effort to bring it to life didn’t achieve everything the kid envisioned, because all of us are flawed, and because forty cents and cardboard props and a lighting director who can’t find the B-61 bus. And both in spite of and because of those flaws, the audience rose at the end and said “we value you and your work. We value you and your aspirations and your imagination.”

That, I think is the enlightenment of the before and after. And it’s not a light shining on you from above somewhere, from some metaphorical set of twelve instruments, but it somehow comes from both within and without - as someone once said, quick, and powerful, and sharper than any two-edged sword. And, as someone else once said, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces, as if it were a scimitar, and feel its sweet edge dividing you through the heart and marrow.

That, I think, is what a positive experience of success is.

I started writing this post thinking I knew what I wanted to say. Whatever extent it may seem complete is an illusion. As I used to say after the final ovation, “Fooled ’em again.”

The hard part about getting it at least partly right has constantly been trying to put aside thinking of this post as a piece of writing - the product - rather than a piece of thinking - the process. I’ve been trying to get the ideas right the first time, in finished form, instead of practicing discovery and being comfortable with messiness.

Another of our partners, Ian, constantly used to repeat, “Process is product.” At first I struggled to understand what that even meant. Then I struggled to believe it. It makes a kind of sense to me now, if only because I wouldn’t have gotten here myself without making myself sit and write every morning, and without other people saying “what you should do is sit and write every morning,” and helping me do that.

Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.