an honest mess (part 1 of 2)

When we were producing a show, I naturally wanted everything to be perfect. That’s not a bad desire. It comes from the right place. Part of it comes from the right place, anyway. Part of it comes from ego - look at what we did - and part of it comes from fear - don't laugh at us; don't walk away disappointed. But enough of it comes from a genuine desire to do one's best work, and to enable the audience to be immersed in the action of the play, the emotion of the play, and not be distracted by a door that won't close(1) or an unfocused light. Or, less technically-oriented, by someone forgetting their lines, or someone remembering a line that doesn't ring true, or a giant hole in the plot. Or a story that doesn't hang together at all, six giant holes in search of a plot.

The notion of the “well-made play” began in France in the 19th Century, when a playwright with the absurdly apt name Eugène Scribe started cranking out plays like McDonald's produces Happy Meals; he wrote, or at any rate oversaw the creation of, five hundred plays in his lifetime. There were basic principles to it, although it isn’t clear Scribe himself ever articulated them - he was too busy churning out plots to write critical theory. Mostly, his plays were entertaining, moved apace, and wrapped everything up with a bow. Wikipedia quotes a critic:

Everything is done with the greatest economy. Every character is essential to the action, every speech develops it. There is no time for verbal wit, no matter how clever, or for philosophical musing, no matter how enlightening.

I mean, if that’s what you want. And that is what people wanted, at least in 19th-Century France, and the well-made play became the way theater was done for quite a while. I’m not going to go too much deeper into theater history here, partly because I don't know it despite 25 years running a theater company, but mostly because that's not the point. Suffice it to say that the WMP, even though it became less popular and eventually the thing that later playwrights wrote in opposition to, still echoes through the entertainments we watch today.

In truth, though, that's only partly due to Monsieur Scribe and the accidents of history. We as people have, I think, an instinctive sense of story: of how a story begins and ends; of what parts are important to include and what’s better left out; of not being distracted by unnecessary characters and unrelated events and plot elements that end up going nowhere. We want, to use the good old, pseudo-Aristotelian term, a sense of unity.(2)

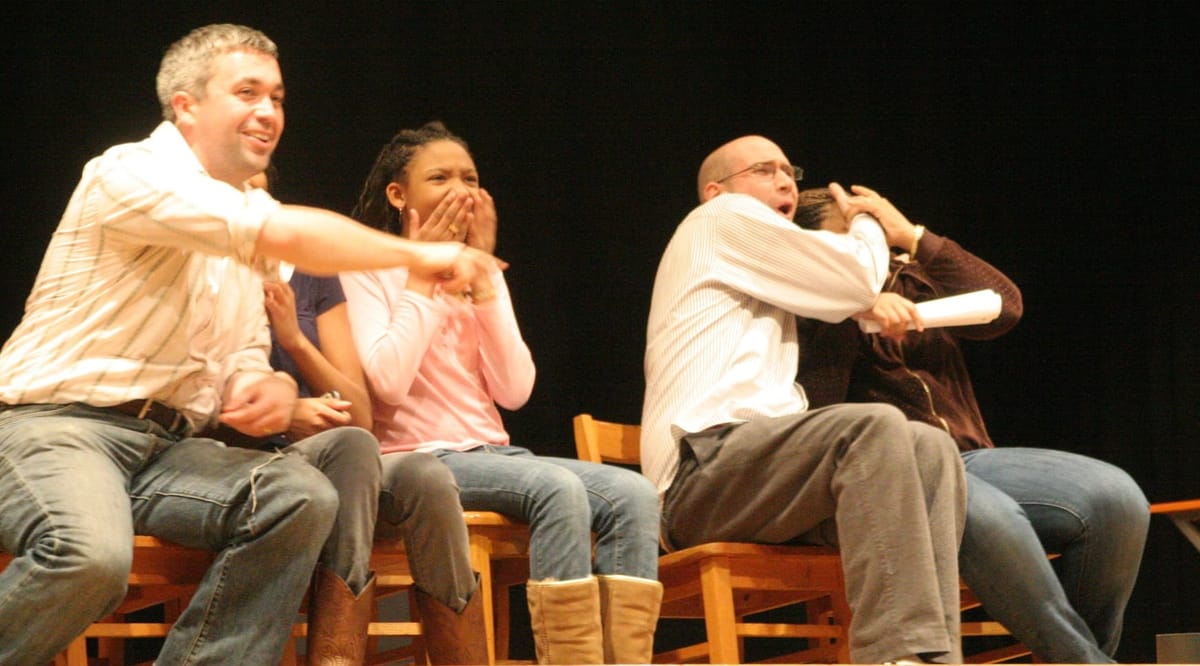

This was not the main focus of our program when we started writing plays with kids in Red Hook. Not that I can recall, anyway. We usually started by working on characters - who is the main character in your play? What is their name, their occupation (a job, school, taking care of family), their greatest dream, their deepest fear, their most important being (mom, child, dog, invisible friend). And what is a secret they have? We would work up a few characters like that, and then get to work at writing.

All this stuff is straight out of the process laid out by Daniel Judah Sklar, by the way, who wrote the book on Playmaking. We tended to be a little more loose when it came to plotting than Sklar suggested, though. For the most part, our approach was: Let two characters talk and see what happens.

Because, you know, life is like that.

The downside was that this tended to result in kids writing themselves into an infinite number of corners. In the more inventive plays, a crime caper would go totally off the rails, and the kidnappers would find themselves in Florida without a plan. A young person would write about two best friends having a fight, which almost invariably mirrored some kind of conflict they were having in their own life, and be totally at sea when it came to resolving it - not knowing how to resolve the real-life fight, of course.

We did have that internalized sense of unity, though, and - again, at least at the outset - we wanted the resolution of the play to be driven by the characters themselves, to emerge out of the elements of the plot.

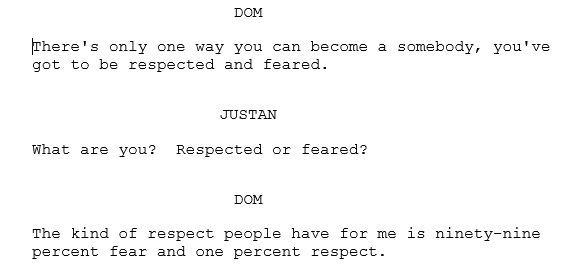

After all, it’s easy to end a play if you just want to end it. A young man named Misha had written one of those gangster dramas - a snowboarder needed to borrow money to finance his X-Games dream, and turned to a mobster named Dom for a loan. Don't worry about how you’re going to pay it back, Dom told him: “You just drink your blue slushy.” Naturally the snowboarder couldn’t come up with the scratch, and Dom wanted payback of some other kind. And playwright Misha found himself just stuck.

“Maybe the kid wins the lottery,” Misha said.

Jolie, who was teaching the Off the Hook workshops at the time, wasn’t having it.

“Maybe Dom falls off a cliff.”

No.

“Maybe there's a car crash and -”

“No! What happens has to tell us something about the characters, it has to be related to who they are!” Jolie insisted

It’s frustrating to write yourself into a box. “When in doubt, have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand,” was Raymond Chandler's advice for such situations.(3) (Chandler didn’t usually have the gunman ice everyone and then turn the weapon on himself, the way Misha might have been tempted to do.) You're kind of faced with two possibilities when you find yourself in that authorial bind. One is the disheartening realization that you have to go back and tear up what you've written and try again - tear up work that you enjoyed, that you committed to emotionally - and that, most importantly, you already did. Nobody wants to have to repaint the whole floor to wipe out their footprints.

The other possibility is that you just have to do the hard work and figure out what you really want to say.

In Off the Hook, we employed the principle of want-conflict-change. This also comes straight from Sklar and Playmaking. A character - maybe a teenager - has a greatest dream, like going to Hollywood to become a movie star. Another character - maybe that teenager’s mom - has a greatest fear, like the possibility that their child will go off into the world and never see her again. Naturally, that puts them in conflict, and although you can mine the conflict for plenty of drama and humor, eventually something has to trigger a change. Somebody has to give: maybe somebody wins and someone else is sad, or maybe they work their way to a solution and resolve a deeper conflict along the way. Basic stuff, but rooting it in the “want” is tremendously clarifying for a young playwright.

This isn’t a made-up scenario, by the way; dozens of kids wrote a version of this conflict. In some ways it’s in the nature of being an adolescent, and in other ways it's our old friend Joseph Campbell coming for another visit. More than that, though: As I’ve mentioned before, we worked across the street from a housing project where the majority of our young participants lived. Some of them were the children of immigrants; others were the third generation living in that same apartment. Sometimes I would look at them, look at parents thrilled at what their children had achieved, see all the hopes and dreams that they had for their kids’ success, and think: to be the fullest expression of themselves, this young person is going to have to leave their family behind.

I guess that’s true for all of us. At moments, it was particularly poignant watching families walking back across Richards Street to their homes.

In Misha’s case, his snowboarder Justan wanted fame and fortune. And Dom wanted ... well, you might say Dom wanted his money back, but at one point, after Justan went off a cliff and broke his leg - a change, in the playmaking sense - that became impossible. So then what Dom wanted was to protect his reputation as a crime boss.

And so Misha found himself facing the temptation to crank up the deus ex machina to pull him out of the box he’d trapped himself in. That’s almost always the wrong choice, no matter how much it thrilled Euripides’ audiences; no matter how much Dallas needed Patrick Ewing back in his role as Bobby. But especially, it’s the wrong choice for a teenage playwright facing a legitimate conflict that he has created, and usually not out of whole cloth.

Because, look: Not often does a kid finds himself in arrears to a mafia boss for ten large. But every young person has found themselves wanting something they can’t have, and even worse, having tried to cut a corner to get the thing they can’t have, and having to face the consequences of cutting that corner. It’s rare that the problem is solved by lucky numbers on a lottery ticket or a boulder landing at the right spot. The process of writing yourself out of that corner, of figuring out how to solve this problem that you created for your characters, provides good and necessary practice for finding a way out of a disagreement or a dilemma - without chasing miracles or involving the cop ex patrol car. The kinds of resolutions Euripides wrote don't show the way to personal growth.

Augusto Boal, the developer of Theater of the Oppressed, wrote that “Maybe the theater in itself is not revolutionary, but these theatrical forms are without a doubt a rehearsal of revolution.” Were we trying to rehearse actual revolution in Red Hook? In the end, yes, although I’m not sure we were quite there by the time Misha was writing his play.(4) At all times we were, however - if it’s not stretching the term - practicing for a kind of personal revolution, the revolution of the self, of the young person trying to learn how to grow into their own adulthood, to figure out how to navigate the hostile worlds of school and home and the interior voices saying, “You don’t know what you’re doing.”

If Boal’s theatrical forms are a rehearsal for revolution, then equally the more common theatrical forms rehearse life as it is. Not just the tired old well-made play. Any form of drama - any form of art, for that matter - that doesn’t question in some fundamental way the way we live, reinforces the way we live. I gave you my definition of art in a footnote a while back: A work (a performance, a piece of writing, a piece of music, visual art, an experience, etc.) in which the audience participates in constructing meaning.(5) With that in mind, here’s Hammett's definition of pop culture: any form of art that expresses what people already believe to be true.(6)

The happy endings that you tend to see in television sitcoms and dramedies, and that kids tended to imitate when they wrote plays in Off the Hook, nearly always bring us back to: If you just do this one thing, if you just make this one change (remember: “want-conflict-change”), then everything is going to be OK again, and the world can go on. Maybe not as it was; maybe everybody learned something in the process. But that one little change, more than likely, will lead to a resolution between two people that fails to address - fails even to consider, to recognize - the conflict has come about because these characters live in a world or society or institution or family that doesn’t respect their full humanity.

In a typical, early Off the Hook play, two friends might have a fight over something - an overheard diss, or a jealous retaliation. They stop talking to each other. Finally one of them sees the light and amends the error of their ways, and the two can return to going to the ice cream store and acting silly.

Or you can see Scrooge, enlightened by the vision of Tiny Tim, who did not die, spreading his wealth throughout the town, buying fat gooses for all and of a sudden treating his employees with respect.

Or if your taste runs to epics, here is the hero, with all his thousand faces, returning from his journey victorious.(7)

And that, as often as not, is a lie.

We like those lies. I like those lies. There’s no end of unhappy endings in the world - you don’t even have to look for them; they will come right up to your door. Why demand unhappiness in your entertainments?(8)

I am not saying you have to. I'm only half-heartedly saying you need to be aware of the lies when they're told. I am saying that, in the course of making theater in our wonderfully complicated, often-divided, greatly under-resourced community of Red Hook, creating that sort of theater was not even a band-aid, but a harmful distraction - a form of malpractice.

It came upon us gradually, I think. Or gradually and then suddenly. There was a genre of Off the Hook works we came to call the "Let’s Be Friends” play. Two kids in school in conflict with each other: a jock and a nerd, or competitors in the talent show, or a bully and a victim. Or all of those at once. The conflict comes to a head; something happens; there's a resolution; happily ever after. As far as we know, at least - as far as the world of the play exists.

That was fine for a while - it was fun for a while. After the twentieth of these little plays that you've produced, it begins to get a bit dull. Now, I will say, one of the biggest risks in any kind of work, but especially any sort of educational work, is that you’ll get bored and end up giving up on something that’s effective just because you as the teacher/mentor/director are tired of it. However, it’s worth asking, why am I tired of this? Is it because I’ve done it too many times and it’s somebody else’s turn? Is it because capitalism has pushed me into a necessary but soul-sucking role, and I just want to break things in some way? Or is it because there’s actually something that I could do better?

I don’t think we would have kept plugging away at Off the Hook for 18 years producing “Let’s Be Friends” over and over again, even if offset by the occasional thunderbolt of a play that a young playwright would unexpectedly turn out. Not the main thing, but a necessary thing: I don’t know if our audiences would have kept coming out for 18 years of “Let’s Be Friends.” In the life of our little theater company, it was becoming a conflict (internal conflicts count, too!) and we needed to make a change.

I don’t know when it happened, or what inspired me to come up with the corny little phrase. Probably some kid had written a play that was a jumbled heap. It would happen sometimes. They would write themselves into a corner like Misha did, or tackle a more mundane but equally insoluble situation. A kid growing up in a housing project apartment confronting poverty or one of its discontents. The playwright conjures a dream. The playwright doesn’t need to be told of the obstacles between her and her dream; she’s keenly aware of them, she probably has parents and teachers reminding her of them. Want and conflict exist; if a solution - a real solution, a plausible solution, not a man with a briefcase full of money solution - if a plausible solution existed, writing the denouement would be a piece of cake.

Somewhere along the way, we started realizing that these plays, the tough ones, the ones that were just strange or surreal, or posed an intractable problem and left the solution unsatisfying - somewhere along the way, we realized we liked them better. They were the ones that made us pay attention. They resonated. They made us keep thinking, “we could have done this better.” They were the ones, most importantly, where the kids grew more, and where the audiences had to think a little more.

They weren’t “well made.” They were messy. And suddenly one day I said to Pink, An honest mess is better than a tidy lie.

(I will pause to note, that is as tidy a little sentence as has ever been written. Just a word of caution to you and me.)

Now: Lie is an unfair word when it comes to a kid’s play. It implies intent, and almost never did a young person intend to deceive by writing a happy ending - a neat ending of any kind. Not even in those Let’s Be Friends plays. First and foremost, they usually just wanted an ending - your typical Off the Hook participant was your typical fifth or sixth grader, and getting done might mean getting to run outside sooner.

Apart from that, all their training from all that pop culture had been, “This is how a story ends.” Maybe the hero prevails, maybe the antagonist has his way, but ends are tied up. So, “lie” is the wrong word, at least when it comes to the kids’ efforts.

But “lie” not unfair when it comes to a second-tier rom-com. Nor was it unfair to us, producing these children’s plays, if we tied too pretty a bow on them. I cannot shake the memory of a fairly bog-standard school-bully-vs-nice-kid play, where I was conscripted as an actor. At the end the school’s authorities were finally engaged, some coercive measure was taken, and the bully was asked to agree. The language was the language of resolution, but the truth of it was like nothing so much as Act IV of The Merchant of Venice, when Shylock has the Christians’ “mercy” forced upon him:

DUKE

He shall do this, or else I do recant

The pardon that I late pronouncèd here.

PORTIA, as Balthazar

Art thou contented, Jew? What dost thou say?

SHYLOCK

I am content.

And - I missed it. I played it as if, yes, that’s how reconciliation comes about, through brute strength. I guess it achieved the play’s unity, maybe even the playwright’s intent, but if there was any truth in that moment, it was in the blatancy of the falsehood.

The truth lives in the phrase “but what about.” It’s uncomfortable to leave the theater thinking, “but what about....” Leaving matters unresolved feels strange, at least a little bit revolutionary. It takes practice to become used to it as a viewer. It takes practice to give it welcome on your stage.

You want to rehearse for revolution? You go back to Augusto Boal.

If you were forwarded this email or found us through a web link, please consider subscribing to Notes for Nobody but Myself. And if you're already a subscriber, I hope you'll consider supporting my work.

(1) Doors onstage don't use conventional door latches, you know. Pink was once in a show directed by the wonderful Walter Dallas, where every time an actor entered through an upstage door they would fumble with the latch or or have to make an elaborate effort to make sure the door would stay shut. And every time, the damn thing would swing open again in the middle of the scene. Finally, Walter told the set designer, "Make. The door. Want. To close."

(2) The so-called classical unities are:

- Unity of action: A tragedy should have one principal action.

- Unity of time: The action in a tragedy should occur over a period of no more than 24 hours.

- Unity of place: A tragedy should exist in a single physical location.

It is safe to say these were a foreign concept to young people raised on television and movies.

(3) From "The Simple Art of Murder," which appeared in The Saturday Review of Literature in April 1950. For what it's worth, he wasn't claiming that made for good writing, he was saying that was the writing they did when he was churning out pulp.

You can find that essay in the collection Trouble Is My Business. Confusingly, Chandler had previously written a different essay also called "The Simple Art of Murder" - come on, Ray! - that appeared in The Atlantic Monthly six years earlier. The "man with a gun in his hand" line doesn't appear there, but he did write in that essay, "The English may not always be the best writers in the world, but they are incomparably the best dull writers." Make of that what you will.

(4) Also, I should note, if I haven't already, that I'm a lousy revolutionary; I'm always thinking about the people who will be hurt in the process. Then again, one of our friends who is considerably more anti-capitalist than I am, or at least more learned about anti-capitalism, would say "You will never hear me use the rhetoric of revolution" for that very reason.

(5) If you don't remember, it's because it was in a footnote. Read the footnotes, people!

(6) Probably stolen from somewhere; I've had it in my head so long I couldn't possibly tell you where I got it. Also, it deserves to be said that people believe a lot of different things to be true, and so pop culture for one looks degenerate to another. Which sort of makes the definition fall apart, so don't dwell on this too long, please.

(7) Campbell just won't leave us alone. Or maybe I've found a hammer, and the entirety of narrative art looks like a nail.

(8) There are, I suppose, some people who will tell you that that is the difference between entertainment and art. Stay away from them. They'll want you to believe that art isn't fun, that you shouldn't laugh while looking at a Vermeer, or feel joy that Mimi and her friends in that garret lived their lives authentically.