an honest mess (part 2 of 2)

Second part of my exploration of how we got comfortable with plays that left us uncomfortable. Part 1 is here.

Want-Conflict-Change.

Want: Let’s see if we can get kids to write plays that aren’t so trite.

Conflict: This is what we've always done, we’re used to it.

We tested out the change with a different program. Pink had been doing work with a Theater of the Oppressed group in New York City called TOPLab, led by the formidable Marie-Claire Picher. Theater of the Oppressed encompasses many forms, but probably foremost among them is “Forum Theater,” in which participants create short dramas that end with unresolved conflicts, or sometimes with unsatisfactory resolutions. An abuser continues abusing, for example. A bully, rather than becoming friends with the kid he’s picking on (or being smashed by a boulder), keeps getting away with it because the other kids are afraid of him and the teachers keep saying, “I can’t do anything if I didn’t see it.”

Forum Theater allows the play to remain unresolved - in fact, encourages it - and then asks members of the audience to find a moment when they can intervene to fix things. Almost invariably, the audience member’s solution either doesn’t work, or involves some kind of magical thinking (not a boulder, maybe, but an antagonist suddenly discovering empathy). And when that happens, the presenter leading the effort to resolve the play - called a “Joker” - asks, “Did that work?” Or, “Does that really happen?”

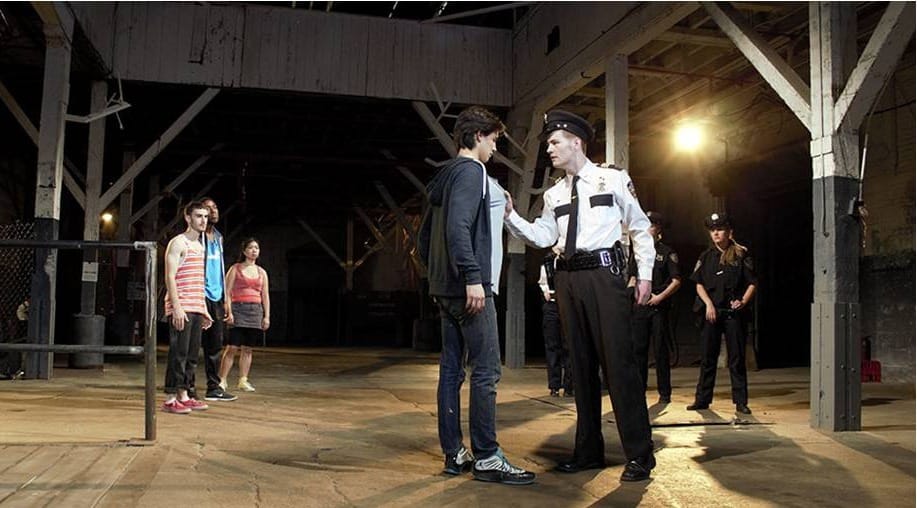

We started creating Forum Theater workshops with older teens and adults - three-day sprints from warm-up activities to presenting a performance. The process didn’t allow much time to think, let alone refine a script or hone a performance. Scenery consisted of the cheapest wooden chairs they sell at Ikea(9); lighting was the mercury vapor lamps in the gym at the local elementary school.

The point of the plays was to be messy. The point of the plays - this wasn’t necessarily an instruction, but it’s the way Forum Theater works - was to leave lots of holes where an audience member could say, “Here’s a moment when someone could have done something different.” The well-made play is written to present a kind of inevitability, like, “yes, that’s the perfect response; yes, that’s exactly what would have happened next.” Our Forum Theater plays - all Forum Theater plays, if done right - leave plenty of spaces for an audience member to say, “That could have gone differently.” The main character could have acted differently. Or someone not directly involved in the conflict could have intervened.

We did these workshops, as I mentioned, with teens and adults, mostly with the performances directed at teens an adults. (Occasionally a young child would decide to fix things.)

Once when we got more comfortable with the form, Pink decided to try it with the kids. We had usually done some number of Boal exercises into our Off the Hook workshops, but now we were going full bore. The warm-up exercises changed. The preliminary writing tasks, to get the kids thinking like playwrights, evolved. And when it came time to write the actual plays that we would produce, rather than starting with an interesting character or two, the prompt for the kids became, “What’s a problem you see in your community?”

This was, I should note, a bit counter to the principles laid out in Daniel Judah Sklar’s Playmaking. Sklar takes the probably wise approach of beginning with characters, and really digging into their inner lives before worrying about the story:

Good writers listen to their characters. You have to let them act - do things. That's what will make your work come alive: your characters listening to each other, reacting to each other. If you plan too much ahead, you'll be pushing them around. And they'll be puppets, not characters.(10)

Kids, having seen too many cartoons and sitcoms - adults too - will have a tendency to pull out cardboard character #37 - “The Bully,” or “The Mean Principal,” or “The Nosy Neighbor.” We ran into that, and part of the challenge of our Off the Hook workshops became making sure, having assembled these skeletal figures, the young playwrights put some flesh and blood around them. We weren’t always successful at that, I suppose, but equally we weren’t always successful at that while following the Playmaking principles to the letter.

But to get back to the point, when the prompt is “What’s a problem in your community,” there tends not to be a simple solution, because if there were a simple solution, the problem would have gone away. And the change - our change, Falconworks’ change - was that we started embracing, even encouraging, plays where kids wrote themselves into a corner.

Not just kids, either. After we had established ourselves in Red Hook, we started doing “mainstage” productions. We mounted a Shakespeare production one spring - our own take on it, which was a good take, true to the spirit of the work and unpacking some of its implications in the modern world. It told a story about two young people from different sides of town who fall in love. In their effort to be together without their families’ intervention, both end up dying. You know this one.

Not so different from some of the kids’ plays (although they tended not to resolve in double-suicides). A tragedy to be sure, it says so right there in the title, but in the end the lovers’ sacrifice leads to the two families reconciliation: “a glooming peace,” perhaps, but a peace nonetheless. And for that, we can believe, if we choose to, that Romeo and Juliet live together in eternity.

In the wrong hands it can feel tidy. The Prince alerts us, “Some shall be pardoned, and some punishèd,” and sweeps an awful lot away with those words. (Just who gets the pardons, Prince? You’re gonna let Friar Lawrence and his herb-dealing take the fall for this one, right?) (11)

In our hands - Pink’s hands - we weren’t quite so bold as to untidy Shakespeare’s ending completely, but we succeeded in making the young lovers’ deaths, and the chain of events that led to them, resonate enough that one audience member reflected afterward, “Where are the grownups in this play?” It’s easy enough to say the two houses shouldn’t have been holding on to that ancient grudge. What are they about while their kids are fighting in the streets, biting thumbs at each other, or running off to the Friar to be married? What was the Friar thinking? Where has the Duke been, surely aware of the ongoing enmity between Montagues and Capulets, but not actually intervening until people are dead in the streets?

Enough mess there to enable us to stand up the (wonderful and powerful!) love story of R&J as, as well, a trenchant and angry indictment of society. To make it worth presenting in a community where police roamed the streets looking for brown kids to harass.

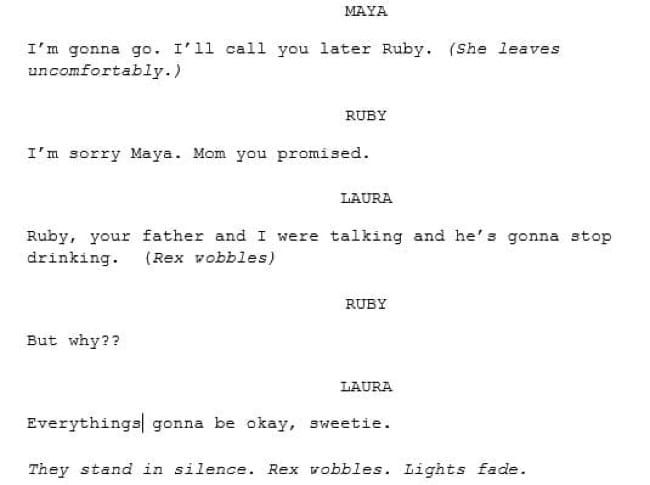

So the spirit of Forum Theater, of Theater of the Oppressed, began to infuse all of our work. Back in Off the Hook, we were no longer insisting the kids had to come up with a didn't necessarily insist that the kids found a resolution. So where a previous family drama had ended with a jaunty little song that included the lines

I'm happy we’re together and I love you so much

I’m through with the boozing and abusing’s no crutch

a later playwright named Abi ended her play differently.

Less tidy, certainly. Less immediately cheerful - but also more truthful and, maybe, better suited to finding solutions to real problems in kids’ lives, in their communities lives.

Not all of the “new” Off the Hook’s plays were as stark. The kids who worked with one of our stalwart dramaturg-directors, Pete, invariably seemed to end up writing a musical number. We still had plenty of room for happy endings, when that was what young people wanted to write. Just - nobody was insisting on that, and it freed the young people to explore a little more openly.

It did present another challenge. I would love to tell you the tidy lie that our audiences embraced it, theater people began flocking to us, we became a model for a new way to do children’s theater, the grant money poured in.

We became a model in one part of the theater world. We brought one of the kids’ shows to the conference of Pedagogy and Theater of the Oppressed, where about 500 attendees saw the play and, if it’s not too much chest-beating to say it, had their eyes opened by the discovery that it was possible to do T.O. work with young people as well as adults. But our Red Hook audiences? I don’t know if they ever quite figured out the change we were making. Or, if I may, they had been thoroughly trained by a lifetime of satisfying endings. Or maybe deep in our humanity there is some instinct that says, “this is how a story is supposed to end.”

Our houses grew a bit smaller, at times dwarfed by the 200-seat auditorium we were used to working in. Funders, who tend to measure things by butts in seats, by “growth,” didn’t necessarily see the value in what we were doing. In the visible ways, it may not have looked like pivoting to Forum Theater was a roaring success.

I choose to believe it was a success in the ways that mattered to us: “We will create work that is truthful”; “Some truths have had more opportunity be told than others, and we will seek to prioritize truths that have not been told as often.”

I wish I had my own tidy ending to offer here. Life and a pandemic intervened right around the time we were figuring out what was next. But in place of what might have happened with Falconworks, I can at least tell you what happened with Justan and Dom in Misha’s organized crime caper.

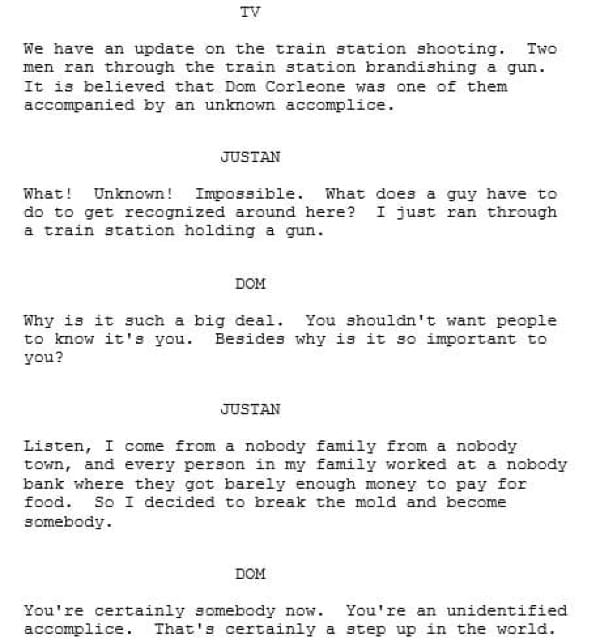

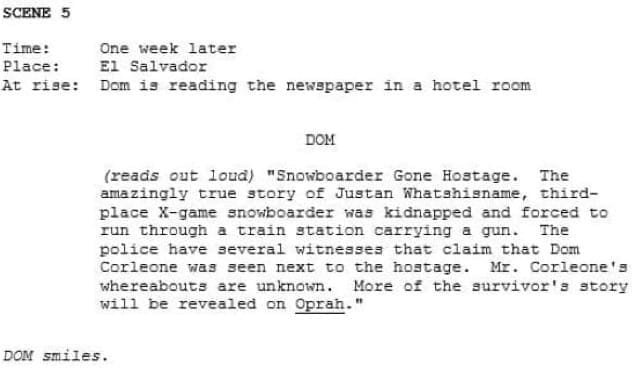

Justan tries to bolt town; Dom tracks him down at the train station. At that point Misha followed Raymond Chandler’s advice and had Justan pull a gun on the crime boss (technically, there wasn’t a door involved). The two find themselves on the lam, holed up in a hotel room watching the news:

Eventually, they find their way to common ground, and Dom hatches a plan to get them out of the mess.

(You probably had to be there.)

Please share Notes for Nobody but Myself with anyone you think will enjoy it. And if this post was shared with you, subscribe!

(9) They would generally last about five or six shows before collapsing.

(10) Playmaking, p. 84.

(11) Our Friar Lawrence, played by Pink, literally showed up onstage surrounded by marijuana plants, smoking a doob, and exhaling before expounding about how mickle that shit was.