double plays and morality plays

Despite my daily attention to it, I don’t write much about baseball. That’s partly because I’ve lately found myself in the company of people who know a lot more about the subject than I do, and I’m reluctant to embarrass myself too publicly. And, I don’t know how much you, my faithful readers, share my interest in the Summer Game. And recently, let’s be honest, baseball seems a little frivolous.

Maybe not always frivolous, though; every now and then the game and real life converge. Today, such a convergence is eating at me enough that I’m willing to risk humiliation. As for you, reader - well, I offer such apologies as may be required.

The topic at hand is baseball’s Hall of Fame, and what makes a worthy candidate for same. Despite my attention to baseball, I don’t care much about the Hall of Fame. Some people - especially, it seems, the statheads who abound these days - are fascinated by the question of who deserves the title “Hall of Famer” and why. I mostly couldn’t care less. I’m pleased that Bill Veeck is in, so that my alma mater, whose own athletic director described its baseball program as the worst collegiate program in any sport at any level, has a representative. I’ll be happy when José Ramírez, the most electrifying player in the game (non-Shohei division), is enshrined wearing a Cleveland cap. Other than that, whatever.

I am kind of interested in the question of what the Hall of Fame - any Hall of Fame - means. But we’ll get to that.

First, what got under my skin. Joe Posnanski, one of my favorite sportswriters, author of the wonderful Why We Love Baseball and The Soul of Baseball, and whose “Baseball 100" series got me and many others through the first pandemic year, wrote a couple of posts at the time of this year’s Hall of Fame elections. The one that interests me, published after the elections of Carlos Beltran and Andruw Jones were announced, is titled “Weighing Morality in the Hall of Fame.” You may need a subscription to read it, sorry. But I’ll give you the gist:

Joe points out that both Beltran’s and Jones’s candidacies were controversial beyond whether their baseball play merited election: Beltran’s because he helped orchestrate a tawdry sign-stealing endeavor, involving both high-tech surveillance and banging a trash-can lid, that boosted the Houston Astros to a World Series win; and Jones’s because at the end of his playing career he was arrested for domestic violence against his wife. One case of egregious on-the-field behavior; one of egregious off-the-field behavior (Posnanski says “allegedly,” but Jones pleaded guilty).

Posnanski then traces a recent history in which controversies unrelated to playing greatness have kept players from being elected, and calls out specifically the Hall of Fame honoree and board member Joe Morgan for “pleading” with baseball writers, who elect some of the honorees, not to vote for steroid users. The Hall, he writes, “put its thumb on the scale.”

The money paragraph is this:

I’m not discussing right or wrong.... I’m just telling you that, after so many years of this, I feel confident in saying that the vast majority of writers don’t want the Hall of Fame plaque room to be the morality play that it has become. They want it to be a hall of the best baseball players who ever lived.

So let me respond a little bit.

First: At this point in time, I have no patience for moral fudging. Or for a dissembling phrase like “I’m not discussing right or wrong.” Right or wrong is the only point of the post. “I’m not discussing right or wrong” simply means “I’m not going to be forthright enough to share my opinion with you." Well, Joe’s opinion is surely reflected by the fact - which he states - that he voted to enshrine both Beltran and Jones. That’s as definitive a statement of right and wrong as one could want to offer; everything else is clouds of smoke.

And similarly: At this point in time, I have no patience for abandoning questions of morality entirely. In case the cowardice(1) of “I’m not discussing right or wrong” wasn’t enough, Posnanski refers to the question of whether transgressions against the game or society ought to factor into one’s presence in the Hall of Fame as a “morality play.” It is true that the question of whether the future generations such as may care to visit Cooperstown, New York, must come face-to-face with plaques honoring Carlos Beltran and Andruw Jones pales in comparison to, say, kidnapping refugees from violent lands out of their homes and returning them to countries where they will be tortured or killed, or shooting mothers in the face. But “morality play” implies that the whole endeavor to insist on values other than wins above replacement is a sham - is, as the kids say, virtue signaling. I beg to differ. Read the words of writers who explain why they would not vote for Andruw Jones. Their beliefs are, I venture to say, serious and sincere. To wave them away as a “morality play” is, to borrow a phrase, to put one’s thumb on the scale.

Second: At this point in time, I have no patience for being unwilling to make hard moral choices.

To begin with, I must be clear that I don’t believe Posnanski.

I don’t believe that he - or “the vast majority of writers” he conjures up(2) while not offering his own opinion; see above - want the Hall of Fame to be solely “a hall of the best baseball players who ever lived.” There is a line, somewhere.

On the field, maybe it’s nowhere near Beltran. But if a player actually caused his team to lose the World Series, intentionally, because he was paid by a gambler; or if a player paid an umpire to consistently shade calls in his team's favor; or if a player hired a couple of goons to kneecap Shohei Ohtani and lessen the Dodgers’ chances of winning - if a transgression of that magnitude occurred, I have no doubt the “vast majority” of writers would say, yes, that’s a bridge too far; this player has no business being permitted to enter the museum as a paying guest, let alone be invited into the sanctum sanctorum.

Perhaps no Hall of Fame-worthy player would ever do such a thing. Then again, you wouldn’t think the best relief pitcher in baseball would spike pitches for less money than he was paid every time he showed up for work. Then again, Tonya Harding exists.

Off the field, maybe what Jones did to his wife wasn’t enough to forbid his enshrinement in the Hall forever. But imagine a player who was willing to sexually abuse clubhouse attendants over whom he held considerable power (wait, you don’t have to imagine). Imagine a former player encouraging death threats against journalists (again). Imagine - this one really is my invention - a former player burning down houses of worship. Somewhere, I am certain, a line exists.

Maybe I’m wrong; maybe the vast majority of writers (and Posnanski) would ignore such things. But if I’m not, if that line exists, anywhere - as the phrase goes, now we’re just haggling about price.

And here’s the thing: the debates as we’ve had them, about the players we’ve had them about, are frustrating and endless because they’re not obvious or clear-cut. For the most prominent of the steroid abusers, the Barry Bondses (there’s only one Barry Bonds), one can make the argument that the drugs weren’t plainly against the rules, or that even if they were, everyone was using them, or that his pre-steroid performance would have merited election to the Hall anyway(3). Does (so far as we know), one incident of domestic abuse merit a permanent blackball? How bad does that incident have to be? If a former player says he was making a joke, does that absolve him? Does remorse matter? Does an effort to make amends? Is there no place for redemption in this world?

They are hard cases. And a thing they apparently say in law schools is, “hard cases make bad law.” Which I invoke here (possibly incorrectly) to mean: Concluding that we should never consider morality as a factor in a Hall of Fame decision, because it isn’t obvious whether one Andruw Jones should be excluded, is packaging up baby, bathwater, tub, and plumbing and sending them all to Cooperstown together. Of course the cases are hard. What led you to think they would be easy?

Perhaps some number of the vast majorityTM of writers feel it is unfair that they must make these moral judgments, that they are experts in baseball, not ethics. My response is simply: That is the job. No one has forced you to take it. You did take it, and now you must do the best with it you can.

They don’t let any old joe like me vote on the Hall of Fame inductees. Own the responsibility you’ve earned and accepted.

Which brings us to - take a breath, folks; hydrate; we’re still going -

Third: At this point in time, I have no patience for people ignoring rules governing a responsibility because they find the rules’ moral dimensions to be inconvenient.

The rules governing Hall of Fame voting by members of the Baseball Writers Association of America state, in part:

Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.

Each of those criteria is marvelously undefined; even less is there any indication of how a voter ought to balance the different factors. What is the distinction to be made between “record” and “playing ability”? Is it ninety percent on-the-field stuff and ten percent the rest? What exactly is meant by “contributions to the team(s)” other than the previously listed considerations? It’s easy to look at the instructions and call them vague; from vague, it’s tempting to skip to “Since the rubric isn’t plainly laid out, I’m just going to substitute my own criteria.”

Vague though whole directive may be, however, it is entirely specific in its inclusion of certain factors: Integrity. Sportsmanship. Character.

The inclusion of these three words, together generally referred to as the “Character Clause," does not strike me as accidental. Nor does it strike me, as it apparently does the silent - sorry, “vast” - majority of writers, as a trifle to be ignored. Taken together, those three criteria are half the criteria offered. It does not seem likely that their initial presence was accidental, nor that their continued presence has resulted from shiftlessness. Someone - maybe Joe Morgan - has insisted on continuing to make integrity, sportsmanship, and character considerations in voting.

Obviously, each Hall of Fame voter gets to make his or her own decision as to how much to weigh these factors. One could say, I suppose, “I weighted character 0.001 percent, sportsmanship the same, and integrity 0.002 percent - leaving 99.996 for playing record and ability and the other thing.” That would be, perhaps, technically in keeping with the rules. You can judge for yourself whether you think it would be in keeping with the spirit of the rules.

Put plainly: If you do not include character and integrity as important factors in deciding whom to vote for in a Hall of Fame election, you are not doing the job you have agreed to do. It is not more complicated than that. There is no more wiggle room than that. The job description states that you will consider integrity, sportsmanship, and character. If you vote without doing so - if you regard considering domestic violence or cheating a “morality play” - you are lying to the Writers Association and the Hall of Fame about the work you have performed, and you yourself are lacking in integrity.

Posnanski, it seems, does not like these rules - because of what I’ve suggested above, or maybe for some other reason, or maybe this is all a bunch of steam in the service of some other agenda, I don't know. Let’s assume, based on the evidence - based on the thumbprint that remains on the scale - that he does not like the rules. The valid choices available to him are:

1) Follow the rules anyway.

2) Don’t vote in Hall of Fame elections.

You think these rules are bogus? Inconvenient? Difficult? Send the Hall a letter saying you forfeit your voting privileges. Don’t return your ballot. Drum up a movement of writers who won’t return their ballots.(4) Send in an empty ballot as a protest, with your name on it. No one is forcing you to vote.

The authority you are not accorded is to substitute your own criteria for voting.

Wildly unrelated, but I keep thinking about a couple of literary characters. The first is near and dear to my heart, Sam Spade from The Maltese Falcon. Spade never liked his partner, Miles Archer. But he goes chasing all over San Francisco looking for the black bird and putting himself and others at risk because

When a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and you’re supposed to do something about it.

The other is Jackson Lamb, Gary Oldman’s character from the streaming series Slow Horses. Lamb seems to hate everyone around him, most of all the knuckleheads he’s been tasked with babysitting because they’re too incompetent or otherwise unreliable to put on actual cases. He continually makes a point of how much he can’t stand them. But he goes to the wall to protect or defend them, over and over, because, as he says, “They're my joes.”

You take a job, you have a responsibility to do the job.

I will note: It is not clear whether or how much Posnanski, or any others among the amoral majority, have ignored the “character clause”(5) in their voting, this year or in any other year. Maybe Joe took those criteria extremely seriously and thoughtfully, spent hours deliberating over Beltran’s alleged rules-breaking, frustrated as he may have felt. Maybe every writer did. Their thoughts are their own. It’s not really the vibe of Joe’s piece, but I don’t want to make accusations without evidence.

I will also note: I probably could have picked out a hundred other writers to make this same diatribe about. Joe Posnanski is simply unfortunate that he has me as a reader, and the others generally do not. For that - for dragging him specifically - I apologize.

But, I sense that Joe Posnanski and I do have a fundamental divergence with respect to what we think the Hall of Fame ought to stand for - meaning specifically, the “Plaque Room,” where the enshrinees are honored.

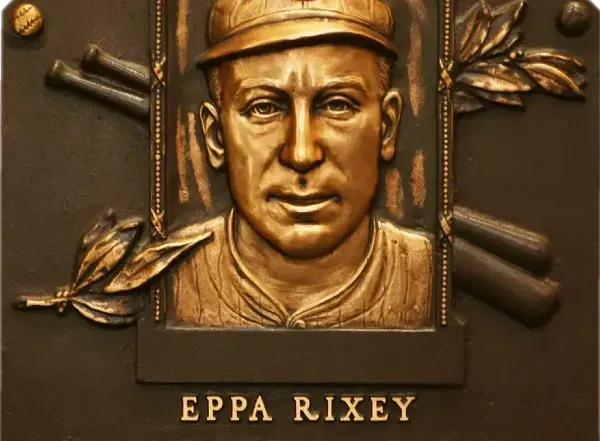

I mentioned back at the start that I don’t really care who shows up in the Plaque Room. Eppa Rixey is there, which I think is great, because Eppa Rixey is an amazing name. Many people will tell you Eppa Rixey has no business being in the Plaque Room, based on his playing career, and I doubt he was of such sterling character and integrity that it outweighed his on-the-field shortcomings. But I don’t care one way or the other, except that I like knowing the name Eppa Rixey.

I do care that José Ramírez will be there, because he’s compelling to watch, and a joy, and he chose Cleveland.

But I am more interested in the question of why we go around creating Halls of Fame - any Hall of Fame.

A little history: The first Hall of Fame to use the name was apparently the Ruhmeshalle in Munich, commissioned by Ludwig I of Bavaria to honor, Wikipedia says, “laudable and distinguished people of his kingdom.” It was followed in the United States by the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, at what was then the Bronx campus of New York University. As described in contemporary news articles, its purpose was a little vague, other than that some sort of structure was needed to help shore up a hillside. The Wikipedia article takes care to note that "fame," as used at the time, indicated renown - “a state of being widely acclaimed and highly honored” - not mere celebrity.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame followed up some years later. Its purpose, Posnanski will tell you, was to drum up tourism in Cooperstown. Like every organization worth its salt, it has a mission statement, and if you thought the criteria for Hall of Fame elections was shrouded in ambiguity, you will not find further clarity in that mission statement:

The Hall of Fame’s mission is to preserve the sport’s history, honor excellence within the game and make a connection between the generations of people who enjoy baseball.

To honor people - Bavarians, Americans, ballplayers. To what end?

Maybe as a kind of reward, such that they might hear our praise? Candidly, I would think the rewards of a lengthy and successful career in modern baseball would be enough. Or as a kind of incentive? Again, the ordinary incentives are substantial.

I don’t care what the players get out of it, in any case, not any more than I care about the recipients of an award from the Oddfellows. My interest is, what do the people visiting the Plaque Room get out of it?

Does the Plaque Room “make a connection between the generations of people who enjoy baseball”? Maybe - kids visit with parents and grandparents, I guess? I went to the football Hall of Fame as a kid, and I will tell you that the most boring part of visiting that joint in Canton was looking at bust after bust of old guys. I was much more interested in trying to kick field goals. Baseball’s Plaque Room isn’t better; the lighting is terrible, the color scheme is midcentury bank, and the plaques are homely.

Posnanski seems to drift toward the idea that the meaning of the Baseball Hall of Fame is, as the statistician and writer Bill James says, to express the idea that “greatness is and should be permanent.” Honestly, Joe circles a lot of ideas in that post linked above without quite landing on any of them. And to be fair, meaning is different from purpose; I’m the one asking about purpose, not Joe. When it comes to his view on that question, I am doing a lot of reading between lines.

But for my side I will be direct: The purpose of a hall of fame is to inspire us.

That sentiment is mostly made up. It is open to debate and disagreement. It is unquestionably simplistic and one-dimensional. But when I imagine a parent walking a child into the Plaque Room in Cooperstown, I imagine that the message, spoken or unspoken, is, “These are the best there are. Look to their example. These are the players you should emulate.”

Or as it is inscribed on a gate at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, Take counsel here of Beauty, Wisdom, Power.

Take counsel. Not just, “Wow, that guy was great, I wish I/you could have seen him play,” but, “That guy was great, and on a baseball field or in a classroom or at a job that you go to every day, you should do your best to follow his virtues.” Hard work, persistence, attention, practice, reliability, care, resilience, all the things that go into compiling the records that are represented on the plaques. Perhaps, finding a thing that one is good at and developing that, whether on a baseball diamond or, because few of us are built like modern athletes, in the rest of one’s life.

And: enthusiasm, joy, teamwork, fair play, respect, honesty, thoughtfulness, kindness, love of one’s fellow humans, decency - all the things that go into how one might assess those other attributes: integrity, sportsmanship, character.

Bill James’s statement - that the meaning of the Hall of Fame to him is “the concept that greatness is and should be permanent” - is less a thumb on the scale than a whole boiled ham. It is more notable for what it leaves out than what it includes. I mean, yes, he’s entitled to his personal opinion, his own feels, and he’s not the one who pressed it into Posnanski’s service. But the place is not the Hall of Greatness, it’s the Hall of Fame. Renown: Acclaim, high honor.

Greatness, from the standpoint of baseball achievement, may not vary - although the decline in Eppa Rixey’s reputation begs otherwise - but the standards of honor do, in fact, evolve. “Greatness is and should be permanent” is perhaps the most conservative statement I have ever read; it is practically the bedrock principle of conservative thought. Again, James can be as conservative as he wants to be, I don’t care. On the other hand, as an ethos for how we honor people, his sentiment strikes me as problematic.

There was a time when what a man did to his wife, up to and including rape and murder, was his own affair. There was a time when Cap Anson’s unrepentant racism and refusal to play against Black players was not merely acceptable, but set the standard for the game for sixty years. Or that of Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Leo Durocher stole signs using the scoreboard at the Polo Grounds, and everybody sort of chuckles, because the threat of stealing every sign in every game wasn’t technologically possible. Nobody knows what drugs early or midcentury Hall of Famers took to boost their play, because there wasn’t any drug testing then, and nobody knows how the vast majority of them treated their families, because nobody cared then.

We have - incrementally, not completely - we have progressed from those days. Our expectations for behavior have evolved; our expectations for role models have evolved.

No, I do not expect that baseball players will be role models, all the time. I do demand that the ones receiving, as they say, “the game’s highest honor” meet some standard of character. For my part, it becomes much harder to place any value on that exhortation to take counsel, to care about what is in the Plaque Room at all, if the standard for entry becomes “Lie, cheat, steal, or beat your wife if you must, but do what you have to do to get in here.”

At this point in time, I have no interest in a Hall of Fame like that. If the Hall of Fame is to be a place that ignores the character and integrity of the men enshrined there, I can’t imagine what the purpose of it could possibly be.

(1) Maybe that word is unfair. I’m not sure if I care. I think the “just asking questions” bit has passed its expiration date.

(2) To be clear, Joe Posnanski probably knows ninety percent or more of the Hall of Fame voters well enough to know their opinions on this topic; by “conjures up” I mean simply, “uses that hand-wavy phrase to avoid using the simpler I.”

(3) I find this last defense to be spectacularly beside the point, but whatever.

(4) It is entirely possible, of course, that his post represents Posnanski’s effort to drum up a movement.

(5) The former English teacher in me feels compelled to point out that it is not a clause.