everything is a choice

Guernica and art and everything. part 1

I’m catching up on some old writing projects. It seems I have time now. This is from December 2023. It’s a kind of journal of discovery.

On my first day in Madrid, my first hours in Madrid, I went to the Museo Reina Sofia. My first hours in Madrid, if you don’t count the hour and a half I spent misnavigating the subways and the two-hour nap I took on arrival. The Reina Sofia is the modern art museum, and I might have missed it had it not been the location of Guernica, and had Kathy not told me how wonderful it was.

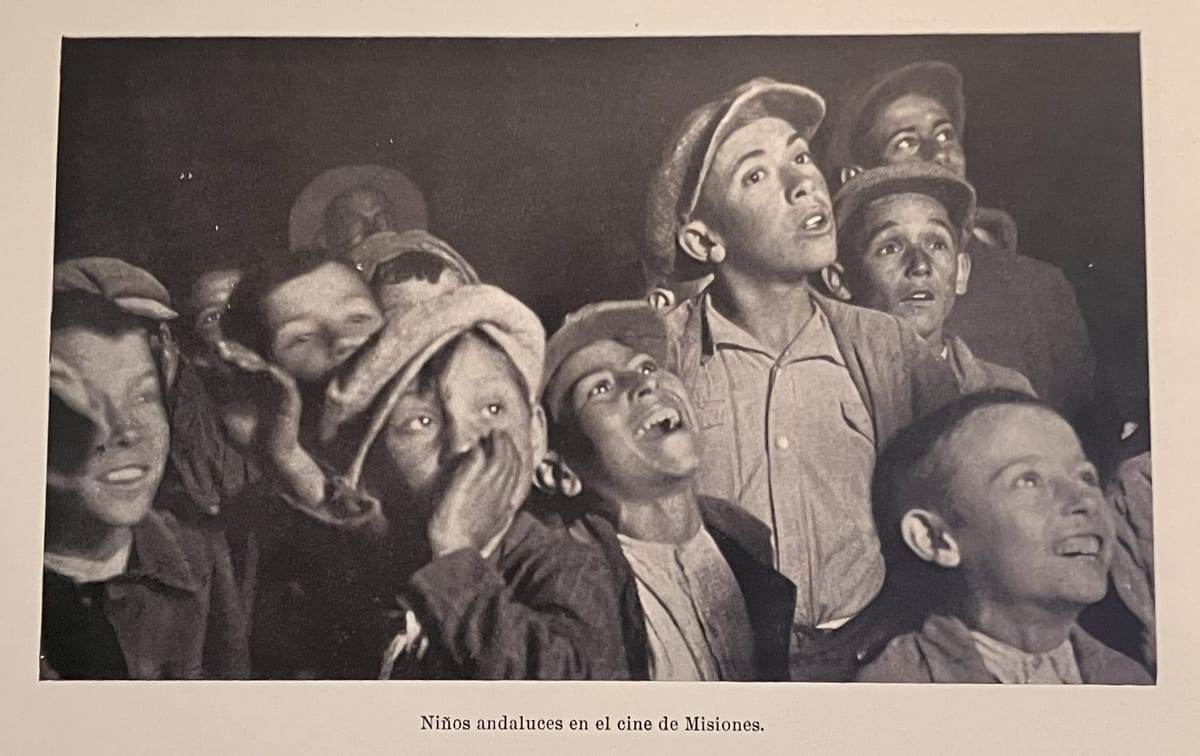

She understated it. The Reina Sofia is overwhelming, in a way that even MoMA doesn’t overwhelm. More in the way the Met is overwhelming: you see a corner of it and your brain reaches the point of “no more,” even though your heart is pulling you toward rest of what’s there. So I ended up learning about an American artist named Ben Shahn, learning that Jim Jarmusch was from Akron, seeing Dali’s Visage du Grand Masturbateur and realizing how much more vivid, how much more intense, are Dali’s paintings than the photographs I know. And discovering that in the 1920s and ’30s, before the Spanish civil war, groups traveled the country bringing movies to seven thousand little towns that had never seen a movie before, along with plays and copies of paintings from the Prado. (That all ended during the war, and I assume for forty years under Franco.)

Of course, the crowds had come for Guernica, as had I - thinking that seeing it first, as the first thing I did in Madrid, would be a good choice. I was right about that, although in truth I did some buildup before finding it.

So, about Guernica:

When I took French in high school with Kelly Moody, he showed us films from time to time. Some of this, doubtless, was him getting through a class he wasn’t prepared for. But some of it was from his heart - it was in reality a class about art and literature that happened to use French as the vehicle. I don’t know if that’s what the administration intended, but you go to school with the teachers you have. On one of these occasions, we watched a French film with a sequence showing a woman fleeing through the streets of Paris. Not only is the name of this film lost to time, I can tell you literally nothing else about this movie. Not the plot, who the woman was, why she was fleeing or from whom. Just that she was running down a sidewalk in front of a high stone wall, the camera tracking down the street as she ran from right to left. Behind her, behind the wall, a cross flashed by, standing on top of a church.

We had a discussion afterward, which I can remember no more than I can remember the film. But at one point we were talking about this tracking shot of her running, I guess, and Mr. Moody said, “I think that image of her running past the wall, represents her separation from the church and God …”

It doesn’t matter what it was meant to represent. To a class of tenth or eleventh graders, or more specifically to me, it was Exhibit A in the way our teachers would analyze things to death, finding meaning in the most minuscule details. Anyone who wasn’t an academic could see it was just a location. Maybe it was close to the studio.

Oh, what little ye know at sixteen.

Many years later - I promise, we will get to Guernica eventually - I was sitting with my mom in the cafe of the Metropolitan Museum. We had spent the morning wandering Central Park, looking at The Gates, an installation by the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude. From our table we could see some of the gates outside, and we watched other visitors exploring and walking around and through them. And we watched as the staff who had been hired to maintain the installation gently tugged at fabric that had become tangled, using long poles to allow it to hang freely again.

As we had been walking, the installation evolved, for me at least, from being decorative - silly, maybe - to a moving work of art. We sat in the Met’s cafe talking about the experience, and the number of choices Christo and Jeanne-Claude had made. Why that color (“saffron”)? Why the height and width, which varied at different points? Why did some gates cross the entire path while others didn’t? Why employ staff to untangle the fabric, rather than let it do what it would? All these decisions. All these choices.

And - I’m not sure if we talked about this at the time - all the choices we had made. To walk around or through. To follow one path and not another, and then, of course, to allow way to lead on to way. We chose - one chooses - to engage with art as one does. Maybe that’s a thoughtful choice. Maybe it’s not. Maybe you’ve heard of Guernica, and you’re not that familiar with Goya, and so you go to the Reina Sofia first and not the Prado. Maybe the Reina Sofia is just close to your hotel.

So: It took me a while to find Guernica. That part of the museum has a layout that I think is meant to lead visitors through art that predated the civil war, through the propaganda produced by the various sides, and up to the star of the show, Picasso’s enormous masterpiece. I hadn’t figured that out, and the museum doesn’t enforce the path, and I kind of came at it through the back door.

An aside: Over the course of a few days in Madrid, I figured out that I had known almost nothing of Spanish history and especially the Spanish Civil War. Columbus Academy may have taught us French cinema, or a certain amount of it anyway, but if the Spanish Civil War came up I don’t recall it. Probably I found French cinema more compelling. What I vaguely knew was, fascism vs … some form of not-fascism, as well as a proving ground for more efficient ways of killing people. And A Farewell to Arms, which we did not read in our English classes and which I am not any more inclined to read now than I was then.

I should add that I knew essentially nothing about Spanish art. I might have known more if I had been more willing to tackle Spanish in high school, but France had infected my imagination, and the example of my brother’s experience, as he carried around a book titled 501 Spanish Verbs, was intimidating. Everybody runs into Picasso, of course; he’s in that unavoidable company along with Van Gogh and American Gothic and the Mona Lisa. The rest of Spanish art history I can’t even say was terra incognita - it was a world that, as far as I was concerned, didn’t exist.

In any event, finally, after some delaying, I entered the room with Guernica.

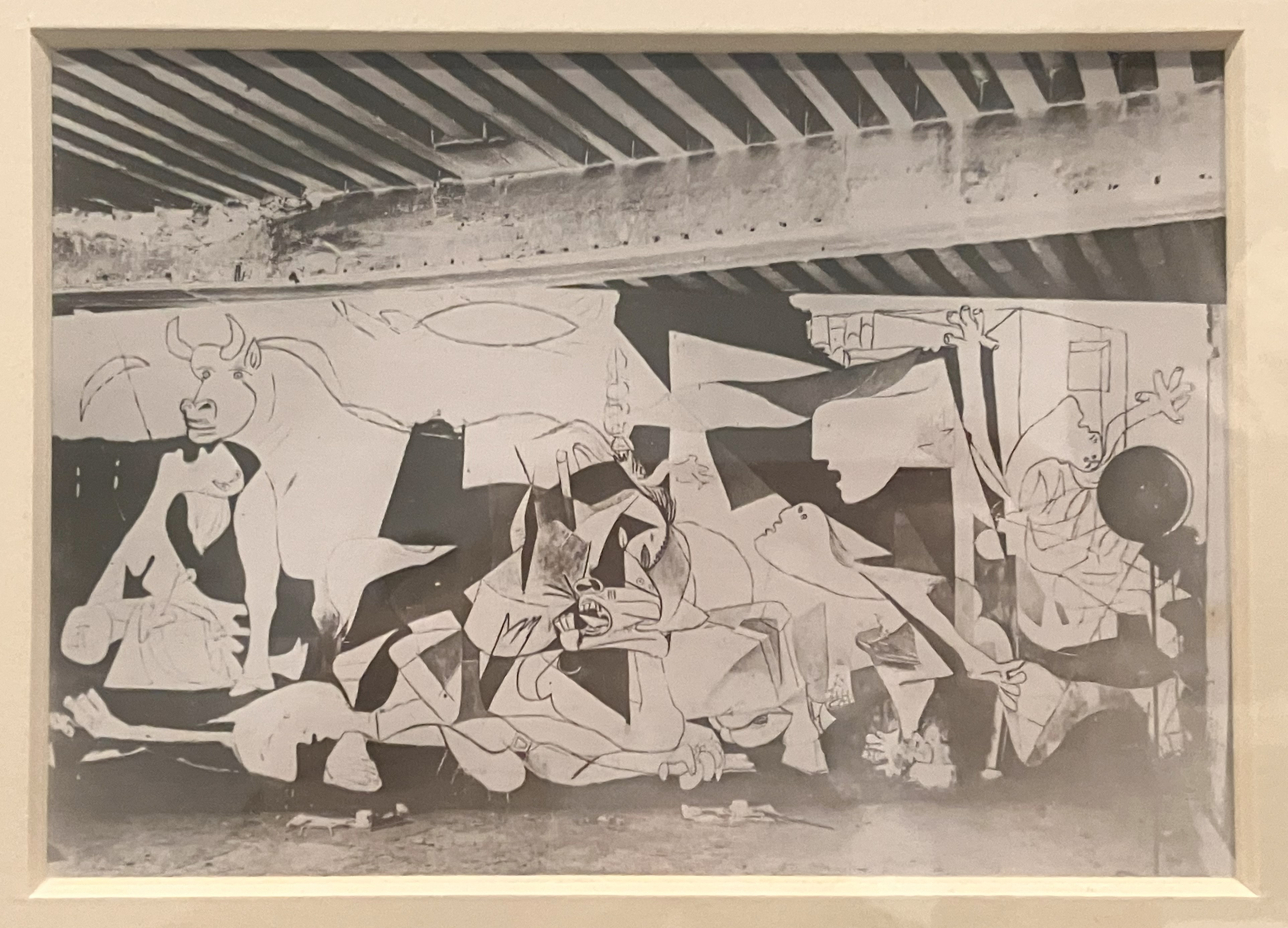

It has its own gallery, enormous, and the painting still fills it. Its scale really is extraordinary, and that’s at least one thing you can never get from photographs you may have seen. My immediate reaction, probably common, was: It’s really big.

Reflecting later, it occurred to me that the scale also means you can’t take in the whole thing at a glance. Not the way you can, again, in photographs. It becomes a horse here, a bull there, a distraught woman over there, a dead man clutching a broken sword on the ground.

It’s monochrome. I guess I knew that, although I remember seeing rather sepiatone photos, and the real thing is stark black-and-white. Not even a lot of gray. Again, photographs fail: one becomes so used to black-and-white pictures that it’s easy to imagine colors where they don’t exist.

Is it moving, is it meaningful, as art? Well, let me talk about that.

If - assuming you’ve seen a photograph - if there’s anything you remember about Guernica without looking at it, I am guessing it’s a couple of the images I mentioned before: a distraught woman her hands outstretched, and the twisted expression of a horse. Or maybe that’s just what caught my notice. (On reflection, I have no idea whether that is actually a woman - I just decided it was somewhere along the way.)

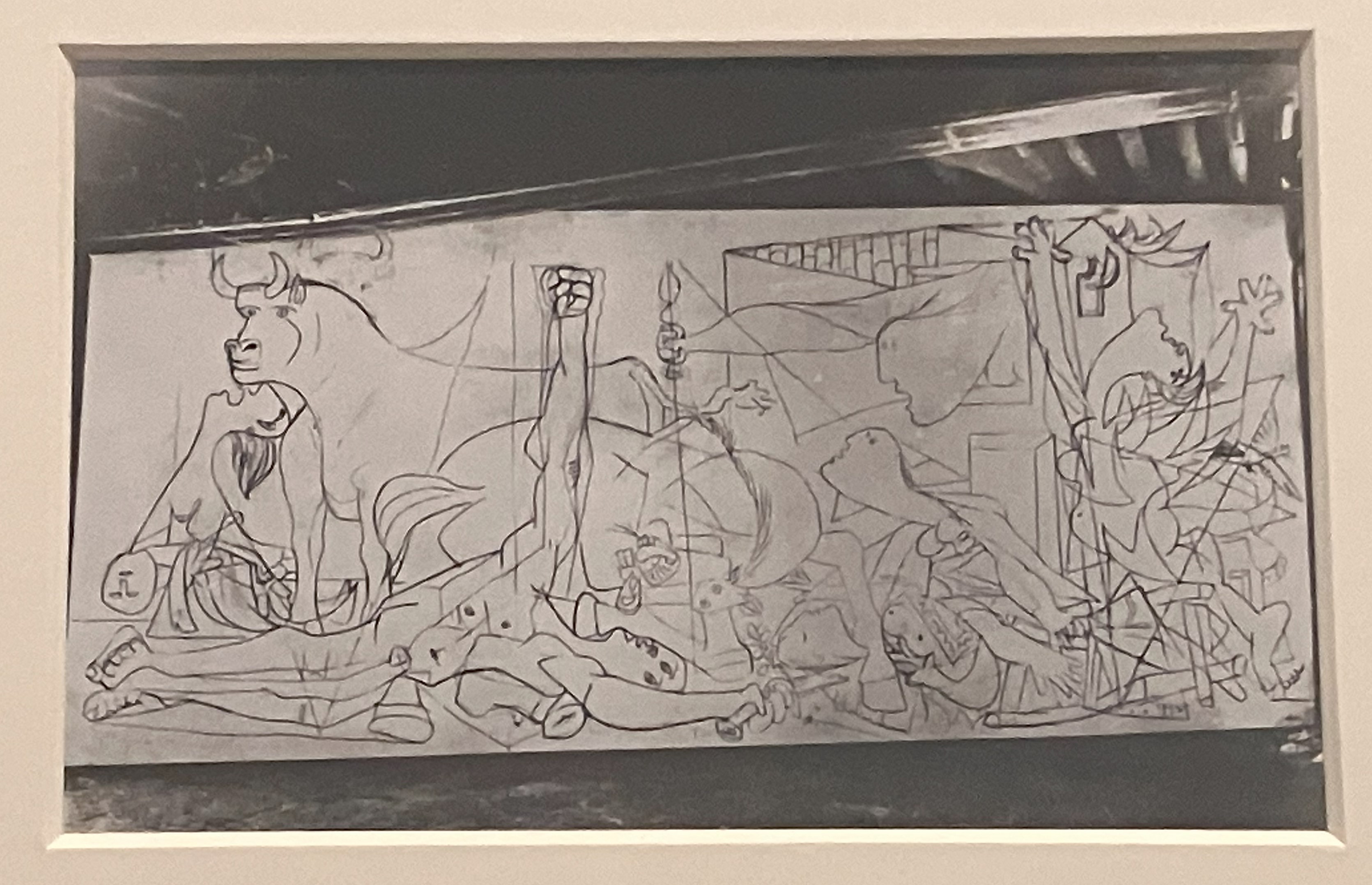

On the opposite wall of the Guernica gallery were a series of photographs, taken by Dora Maar, documenting the development of the work. They fascinated me, because they showed that he totally remade the painting on the canvas. Whatever his plan was going in, Piacsso changed it on the fly. That seems impossible, frustrating - to me, as the little bit of an artist that I am, totally daunting at that scale. I don’t even like crossing out words in my journal.

The photographs showed that Picasso had always included a bull. It was more realistic in the earlier versions, not photorealistic but neither obviously “cubist.” It seems to have been an important image from the start. (Later in my week in Madrid, I learned a little about Picasso’s use of bulls.)

The dying soldier was much more central in earlier drafts. He was partially upright at one point. At another, he appeared to have two thumbs, which I found disturbing, and which - here’s a choice Picasso made - didn’t make the final cut. Why? Who knows. Maybe he didn’t want to call such explicit attention to the unreality of the work. I’m speculating here, obviously and (again) naively.

Most striking to me was that in the earliest versions of Guernica, Picasso made the horse far less prominent. It was cut into pieces, obscured by other images, easy enough to miss that at first I didn’t think it was there at all.

And at some other point he decided the painting needed to be, if not fundamentally, then importantly, about a horse.

I’m not sure you can say Guernica has one primary figure, but if it does, it’s that screaming, writhing, dying horse, a stake impaling its right flank. The horse has drawn the attention of others in the painting; someone is gaping out a window at it, holding a candle as if to discover what could be making such horrifying noises - so I imagine, anyway. It’s one of the epiphanies I had as I gazed for the first time on the real Guernica: this is a painting with a horse at its center. So much so that as the work evolved, the horse changed places with the dying soldier, reduced in the end to literally disjointed body parts at the bottom, hard to see over the crowds.

So, why? Unanswerable, of course, and Picasso isn’t talking - hell, he wouldn’t even say whether his sculpture at Chicago’s Daley Plaza is a horse or a human.

And yet, there it is, a choice, and it’s our job - I really do think it’s our job - to figure out the answer to that question. Why?

And this is the thing: we not only have to, we get to. They didn’t tell us this, exactly, at Columbus Academy; it would have led 16-year-olds down the primrose path of “it means whatever I decide it means.” Not that, Picasso does get some say in the matter. But here is what I was thinking about at 6:00 on the morning after encountering Guernica.

Here, in a painting about a battle - if it deserves that term - where the Nationalists, Franco and his allies, were testing and demonstrating the ruthless efficiency of death delivered from the air, the center of the canvas is commanded by a horse. Frenzied, agonizing, whatever words you want to apply. Bewildered, I think.

Picasso pushed everything else aside for this horse. A horse which was, in earlier days, in the days of war that we now romanticize, an instrument of battle. Don Quixote, that progenitor of the novel, rode a horse, and carried a sword like the broken sword at the bottom of Guernica. Both instruments of war rendered useless under the onslaught of airplanes and bombs raining down on a town of 6,000 people, a town that had existed for six hundred years and only a few years earlier had been introduced to the motion picture.

The horse is an instrument of war until the moment when it is impaled, until the moment of its death, when it becomes again a creature (a created thing - a creation, if you will forgive this atheist, of God). A creature for whom we are, by divine mandate or choice, responsible. A creature capable of pain, of torment, of anguish, of bewilderment - of emotion and thought.

As the solider whom the horse is standing on, clutching in his severed arm a broken sword, is a creature capable of thought and emotion, of love and pain and anguish, turned by propaganda and ideology and the power of other men into an instrument of war, and redeemed only in his death - only in a painting about his death.

And in that way, horse and man are the same, and it takes Picasso placing a horse at the center of his canvas to restore humanity to the center of our thoughts.

Was Picasso thinking about any of this? I don’t know. We have tantalizing documentation of his process, an index of his choices, without explanation. Maybe he just painted. Maybe it was just what he felt. That possibility may be what makes artists different from the rest of us: their ability to intuit and express truths that are inaccessible through thought. Truths where thought and reasoning - like mine here - rather than being aids, are obstacles to understanding.

I left Guernica behind. Madrid awaited me.

Photo of The Gates by Wolfgang Volz © 2005 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation, at https://christojeanneclaude.net/artworks/the-gates/

Reproduction of Guernica by Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, at https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/guernica

Photo of Picasso’s unnamed Chicago sculpture by J. Crocker at https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1878676

Thanks for reading notes for nobody but myself! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.