in the slave lodge

In the Slave Lodge I started screaming.

Ruth, the woman at my hotel, the Ikhaya Lodge, had given me a list of museums to visit. She ordered them for me, nominally for convenience, so I could stroll from one to the next. The first she had listed, though, was the District Six Museum. I don’t remember if she said what it was about, but it was the first one on her tour, carefully marked with an “(a).” It was also the first one she had named. Maybe not accidentally.

The District Six Museum tells the story of a neighborhood in Cape Town, once designated for “coloureds,” until it became a desirable spot and the coloured residents were sent elsewhere. They were given a day to pack. An integrated neighborhood - not integrated racially, of course, but integrated economically, socially, a neighborhood with its own integrity - dissolved.

That specific neighborhood and its exact people may or may not matter more than any others, but they had the wherewithal to tell their stories, and so it stands as an example of the kinds of relocations, the casual social violence, performed regularly by the South African government in the decades when apartheid was at its peak.

And the District Six Museum isn’t my point, really, just that by being first it framed my visit to Cape Town. Maybe, consciously or not, that was Ruth’s intention as she checked me in at the Ikhaya Lodge.

The Slave Lodge was second in the order she had named museums, and although it was not second on her planned route, it was the next one I found.

I went in, paid, they pointed me to the right through a series of rooms explaining the purpose of the Lodge. It was where the Dutch East India Company held its enslaved workers. The rooms described their conditions, their work, especially their revolts. The revolts, the displays explained, are critical to note because they demonstrate how the enslaved people were in no way content with their conditions.

A narrative hides there, one familiar to anyone from the United States who has heard apologists, whether in school or today, explain the advantages of slavery for the enslaved.

At the back of the Slave Lodge a long hallway contained three timelines. One described the colonization of Africa, South Africa especially, the wars and uprisings and subjugation of its peoples.

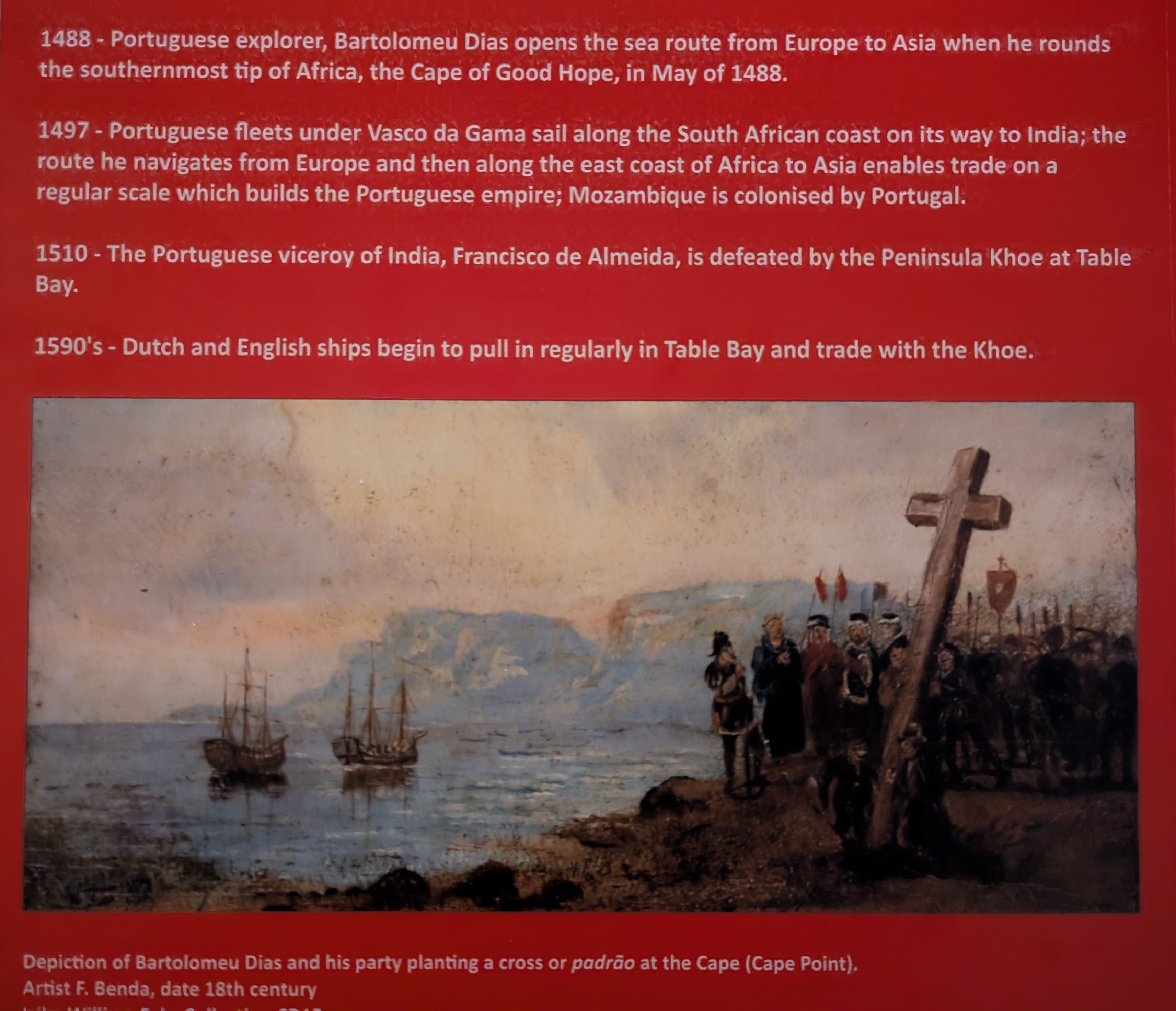

A second laid out the history of the Atlantic slave trade, from the arrival of the Portuguese in West Africa, to Vasco da Gama, that heroic explorer we learned about in school, to growing abolition movements around Europe and the West, and finally the American Civil War and later the end of slavery in Brazil and Cuba.

Seeing the name Vasco da Gama sparked something in me. I probably haven’t spent ten seconds thinking about him since my senior year in high school when I took “world” history. Everyone knows Christopher Columbus was a colonizer. I had never paused to think that they were making us learn, at best with neutrality, about the man who opened Africa to colonization.

So: A spark.

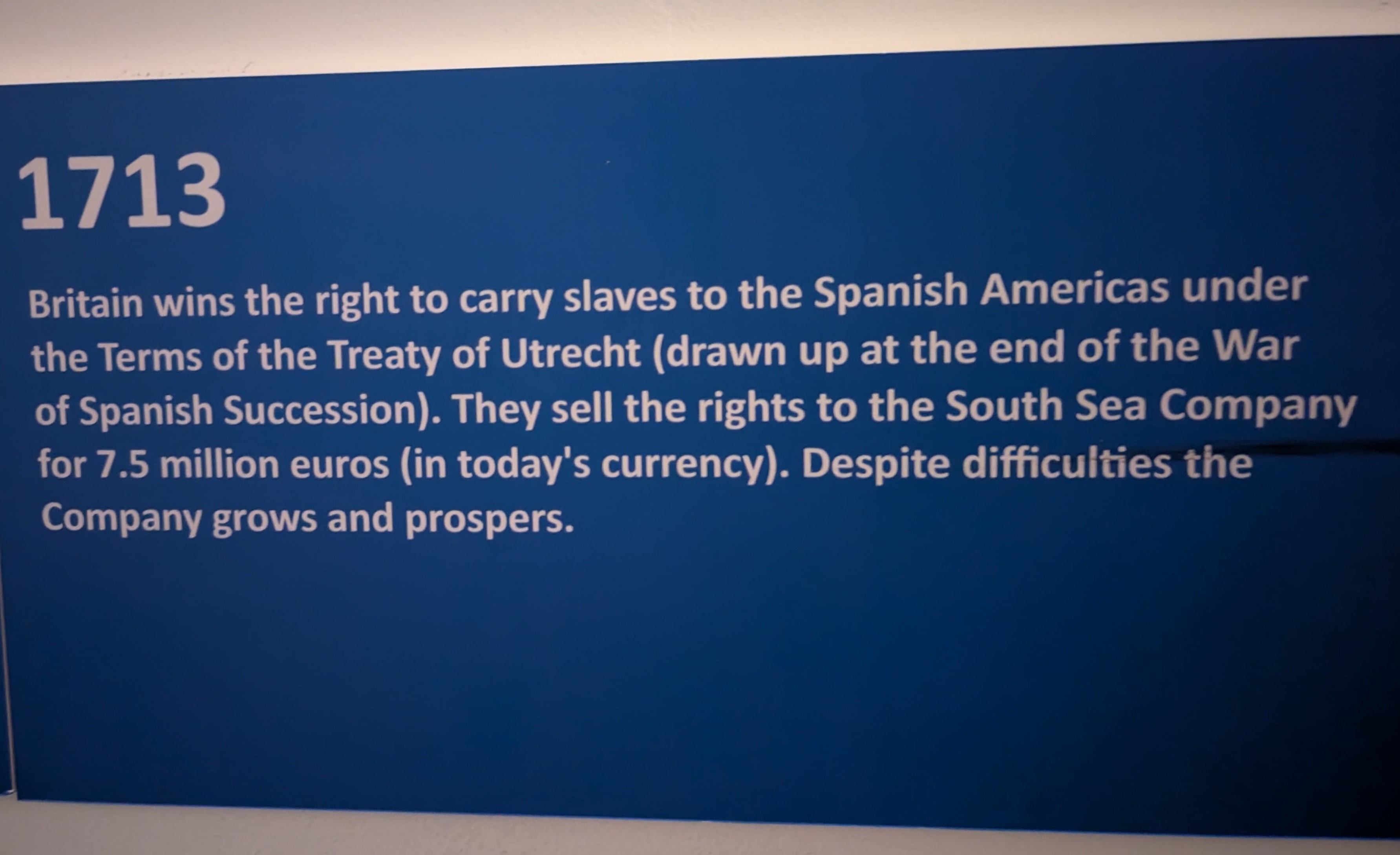

The third timeline, unaligned to the others, told the history of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. It covered the last hundred years or so, taking the same space as 550 years of colonization and enslavement. As if a hundred years holds as much history, as much to learn, as 550 years. As if a whole universe exists in one neighborhood.

I made my way down the timeline. About midway through, I came to an entry, unremarkable, almost offhand, one more fact among many facts.

1713: Britain wins the right to carry slaves to the Spanish Americas under the Terms of the Treaty of Utrecht (drawn up that the end of the War of Spanish Succession). They sell the rights to the South Sea Company for 7.5 million euros (in today’s currency). Despite difficulties the Company grows and prospers.

And I doubled over and started to scream.

No sound came out - I was in a museum, and I have enough self-control not to make a spectacle of myself. No one saw me.

I don’t know what the pain was. Anger. Sadness. More anger. More sadness. At some point, it just became too much. In school they made sure we learned a version of Vasco da Gama, the one where he rounded the Cape of Good Hope and opened East Asia to trade. They did not, so far as I remember, connect his voyages to colonization and the buying and selling of human bodies. They taught us a version of the War of the Spanish Succession. They did not, so far as I can remember, teach us a version of the War that described the profit from the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Asiento de Negros, as part of the spoils.

I do remember that Lou Schultz, introducing the class labeled World History that I took as a high-school senior, explained to us that the class would primarily cover the history of Western Europe, because, he said, “when we talk about world history, we really are talking about European history.” Honestly, it might be the most deeply, foundationally racist thing anyone has ever said to me - all the other racist tropes and biases and laws begin, don’t they, with the idea that somehow Europeans are at the center of a world that itself is the center of God’s universe. We sat there and nodded.

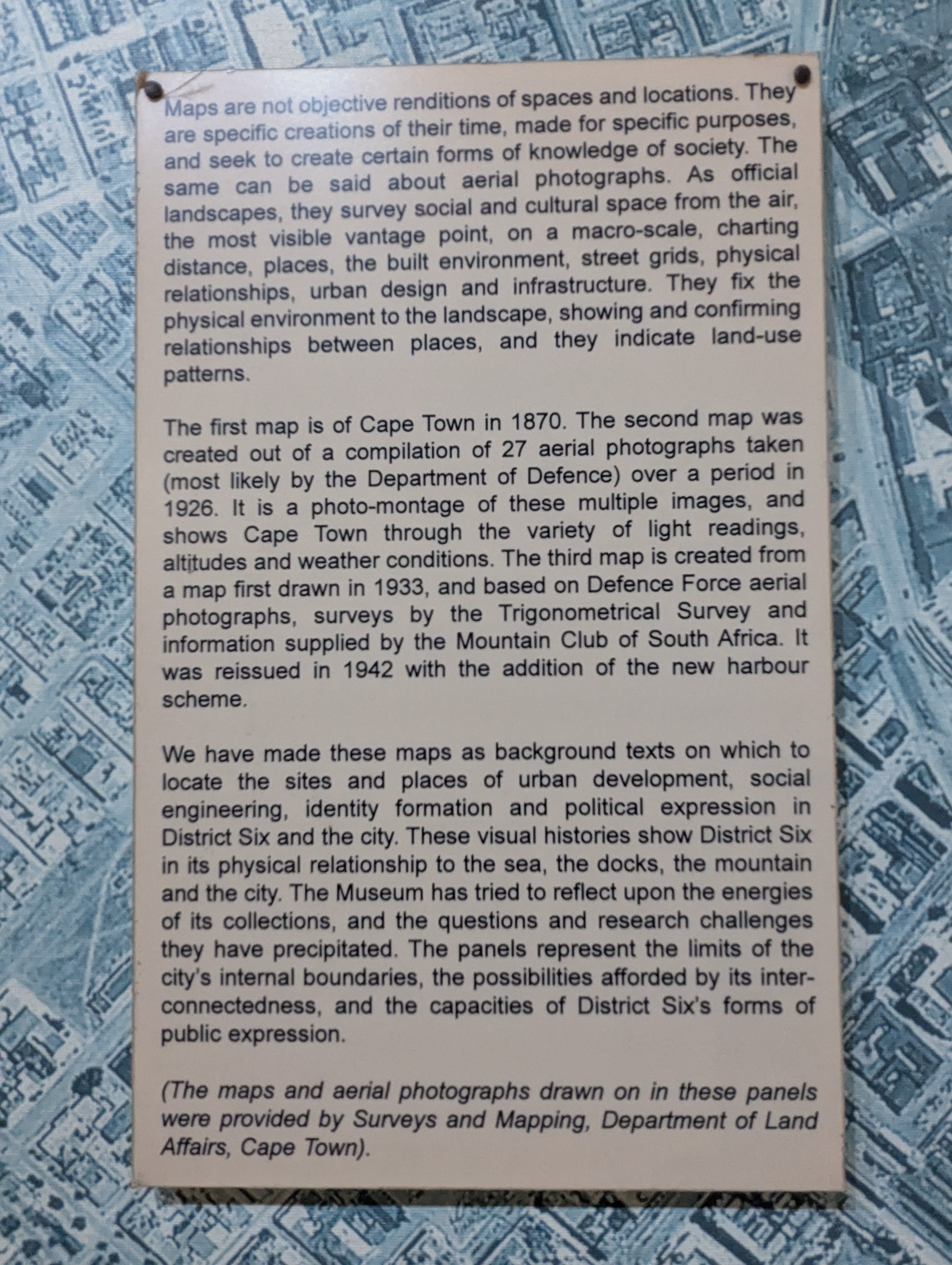

At the District Six museum, a card cautions:

Maps are not objective renditions of spaces and locations. They are specific creations of their time, made for specific purposes, and seek to create certain forms of knowledge about society.

I suppose it’s possible to visit South Africa without seeing any of this, the Slave Lodge or District Six or whatever else I may have seen; to, yes, go to Robben Island and imagine that Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment there was some sort of anomaly, that apartheid was some sort of anomaly in the world. For me, being in South Africa had a way of baring the truth, through the nation’s endless struggle to tell the truth, to shape the truth, to decide what the truth is.

At this moment when my own country, when the world entire, seems so determined to rehabilitate the old lies.

Slave Lodge image © by David Stanley and used under Creative Commons license.

Thanks for reading notes for nobody but myself! This post is public so feel free to share it.