not everything is a choice

back to Guernica

Part two of my immersion in Picasso’s masterpiece. Part one is here.

I had arrived in Madrid on Wednesday. I spent Thursday and Friday and Saturday doing tourist things - walking, mostly; trying to find places listed in the Atlas Obscura, visiting a disappointing Christmas market in the Plaza Mayor, wearing out patient people with my clumsy Spanish and trying to pick up the Castilian habit of saying “vale” in response to everything. And going to museums, as one does. A Spaniard I met had told me the secret to getting into the Prado, the giant national museum, without waiting in the endless line. So I did that, and a third museum, the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum, which I thought I was ducking into for a quick look, and where I ended up staying until they kicked me out.

I hadn’t expected to make art the focus of my Madrid weekend. I hadn’t much known what to expect. I had guidebooks and had asked colleagues for suggestions, but I mostly went in naïve, with beginner mind. So quickly, of course, does one begin to map the streets and landmarks of a new place - this way is the train station; the Prado is over there; Chueca, the gay neighborhood, a bit beyond. I feel lucky the longer I can hold on to that sense of discovery. Maybe it’s not luck but a skill.

I was meant to leave on Sunday. On Saturday afternoon, I received an alert from American Airlines that I could change my flight without charge because of bad weather in NYC. I extended my hotel for another night, worked out the flight change, and told my boss “they changed my flight.”

I hadn’t planned to make art a focus of my sudden extra day in Madrid; I had been thinking of going to the football match between Atletico and Almeria. Well, that was going to end up being the whole day, and I had more to see - the royal palace, the cathedral, the Temple of Debod. And maybe I would stop in at the Reina Sofia to see a couple things I had missed and visit Guernica again.

I expected to stay an hour. Three hours later I was still staring at Guernica, still wondering at its power - while others took selfies in front of it or dragged their kids up to the front. For foreigners, Guernica may be a profound work of art, but for Spaniards it’s a national symbol as well.

Anyway, I had expected to drink in Guernica more, deeper, to make it harder to forget once I did get on that plane back to New York. Instead, I found myself looking at it, once again, for the first time.

By the time I returned to the Reina Sofia, I had spent three days in Madrid - not just three days with Goya and El Greco and Velázquez (although that - importantly that), but three days walking where the street names, the architecture, every stone holds the history of Spain as a Catholic nation. Yes, there were and are Muslims, there were and are Jews and Protestants, but Spain as Spain, as a unified country, is unified under the banner of a Catholic God and king.

I don’t want to get too deep into that; I don’t know enough about it. But I couldn’t escape it in Madrid.

Neither could Picasso, not in Madrid and not in exile. He worked in the context of this history, and in the context of whatever his own beliefs were (and no matter how faithfully he may have lived in accordance with them).

And, maybe more pertinently, he lived within the context of all those Spanish artists who had come before him. I’ll repeat, in case I didn’t make the point clearly enough in Part 1: I didn’t study those guys. I don’t really know what the hell I’m talking about. But Pablo Picasso surely had studied them - how could he have avoided them?

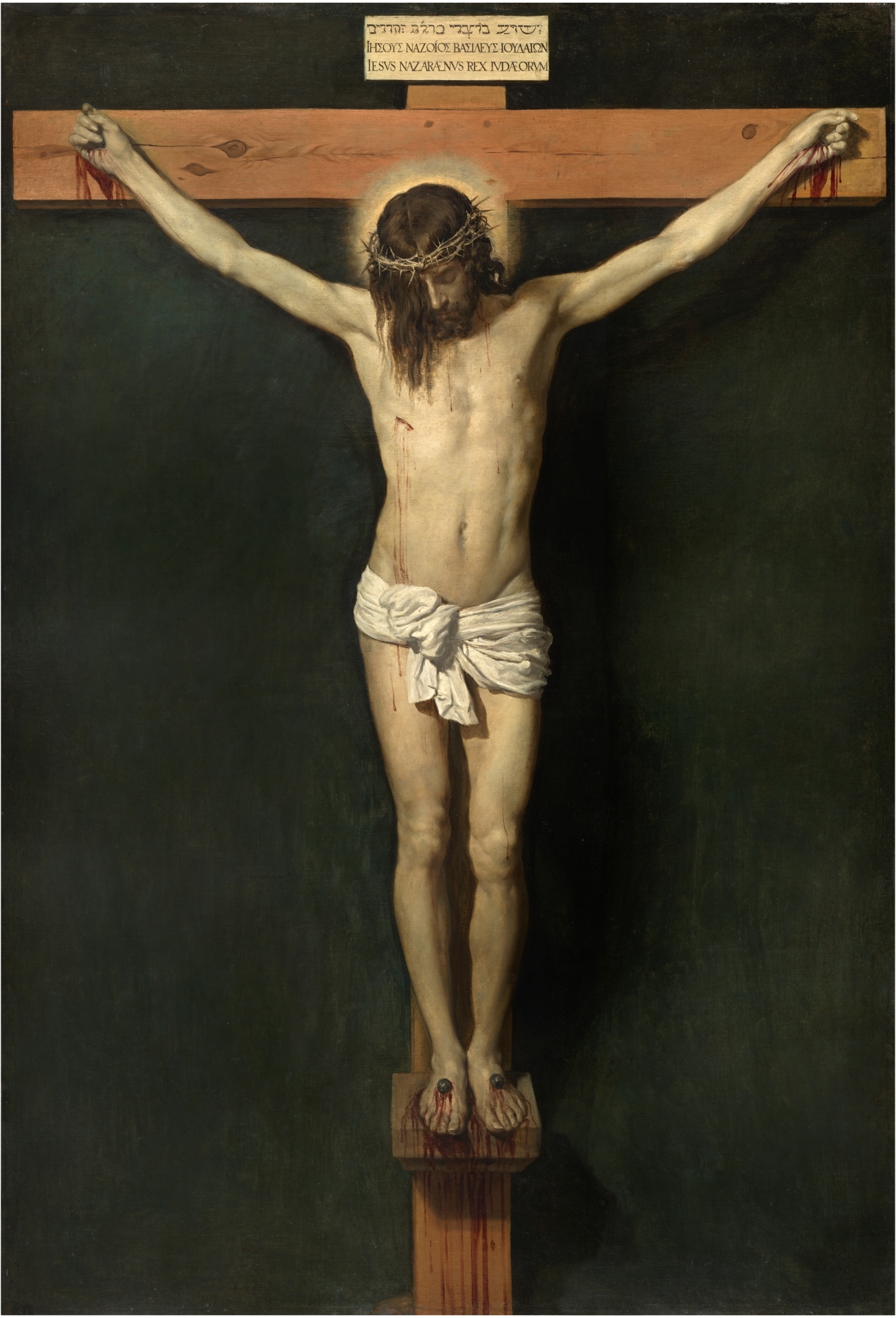

Especially, I think, Velázquez. I don’t exactly know why I think that - I didn’t study those guys! - but it feels obvious. Wandering the Prado, I had the sense that Velázquez had invented Spanish painting the way Cervantes invented Spanish mythology. The burden of painting in a tradition where Velázquez exists is impossible to carry. You can’t match him, you can’t emulate him, you have to invent something completely different. Even so, he’s always there.

So Picasso, turning his back on realism and naturalism and every other -ism that came before, but he can’t turn his back on Catholicism, because it’s on all sides, and he can’t avoid Velázquez and El Greco and Goya, because that call is coming from inside the house. His women, even as he dismembers them, keep being Mary, and his paintings of them keep becoming Pietàs. His men keep turning into Jesus.

I owe the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum for helping crystallize this thinking; they had an exhibition called “Picasso: The Sacred and the Profane” that happened to be up when I ducked in there. It juxtaposed works by Picasso with his progenitors, like this pairing of El Greco’s Christ with the Cross with Picasso’s Man with a Clarinet.

Back at the Reina Sofia, I’m seeing how he embraces everything he’s internalized with Guernica. (I want to say “finally embraces,” but that would imply that I know anything about art history.)

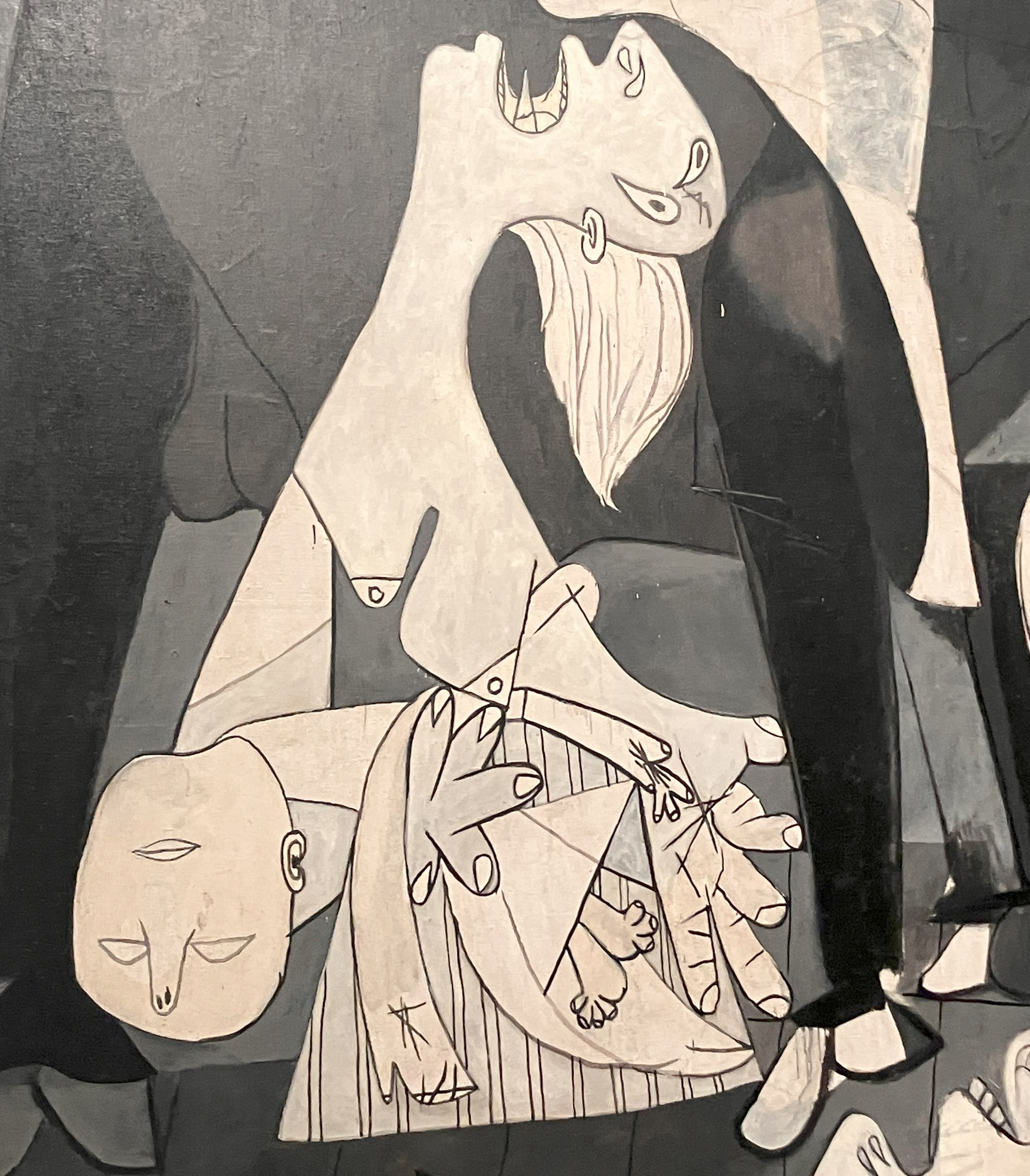

In his literal dismemberment caused by a bombing campaign intended to, as Franco’s propaganda put it, remove the “stain” (the “mancha”) of socialism from Spain, Picasso’s fallen soldier bears stigmata.

Above him sits a woman, screaming, holding in her lap - to the extent she has a lap - a bundle, emerging out from under it two small feet.

Maybe everyone knows this.

The first painting I spent time with at the Prado was a Raphael. I’d never given much attention to Raphael before; his stuff just never interested me. As soon as I entered the gallery, Madonna of the Rose captured me, initially because of the depth and range of the blues against the more somber tones that dominate.

But also, knowing nothing about art history, I snapped this photo because I was amused that St. Joseph is holding a cross and I was going to make some snide comment on Facebook about whether Raffy was aware of his anachronism. Well, of course he was: Everything is a choice, Raphael put that cross there for a reason. As I read in the explanatory cards of painting after painting of the infant Christ and an anachronistic cross, the juxtaposition was meant to symbolize Jesus’ awareness of his divinity, even in his infancy.

In some of those paintings, in most of them, the baby Jesus looks, you know, beatific: glowing, content, perfectly tranquil as everyone makes a fuss over him. Everyone except Mary, of course, who occasionally appears tranquil but more often looks to me like a queen resigned to her role in life.

Occasionally, though, I would come across a painting of mother and child in which Jesus would be looking at the cross with a face that said - in so many words - man, that’s gonna suck.

And likewise, so many of the depictions of Jesus on the cross show him looking heavenward, peaceful, Jesus-like. But occasionally I would find one - this one by our friend Velázquez, for example - where Jesus appears to have discovered he has been forsaken.

I walked past all that Christian art, in that city so steeped in Christianity - a Catholic version of Christianity which seemed new and strange to someone raised in Protestant traditions - and I found myself grappling over and over with the story of God’s love, which passes through so much cruelty on the way to its conclusion. Hieronymus Bosch and his Garden of Earthly Delights, showing us Adam and Eve in the garden where God chose to place temptation; showing sinners in a world where temptation surrounds them; showing the hell that awaits them. Or worse, people clutching at straws in a haywain - literally clutching at straws! Forgive my heresy, but it seems there might have been a more direct route this could have taken.

So Picasso, painting Guernica in this context, Madonna and child and Christ on the cross deep in his soul. In his art, whether he wants them there or not. And he places them, in his dismembering way, in this monumental painting, a painting whose scale alone determines that it will be his masterwork. And I look at it again and think, “Is he offering us hope? With that hand down there, in the lower left, is he reminding us how this will work out?”

Maybe. You could say the presence of the stigmata argue yes, the story will reach its promised conclusion. Out of my own faith, or lack thereof, I don’t think so. I choose to believe Picasso is showing us a version of the Christ story in which Herod’s men find the infant and slaughter him.

Thanks for reading notes for nobody but myself! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.