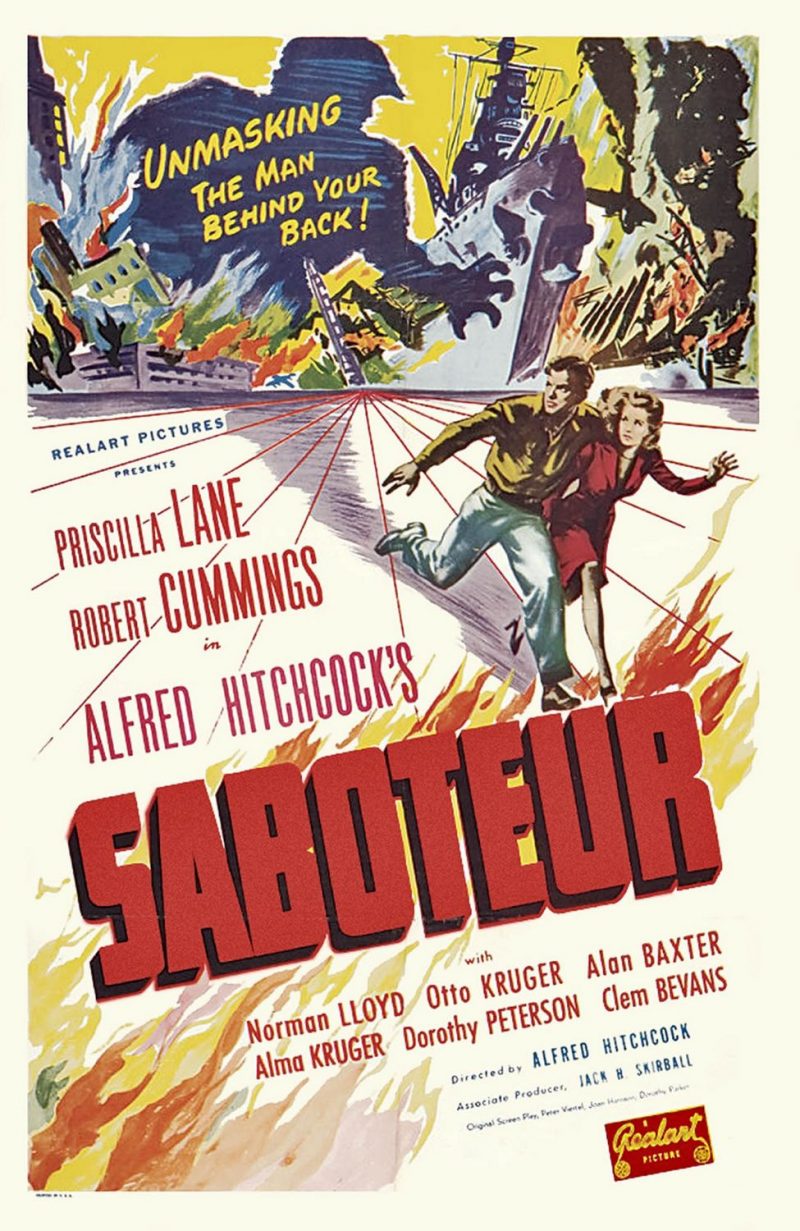

saboteur

film

I rewatched Hitchcock’s Saboteur on Sunday. Minimal thought went into that decision; I was looking for something that wasn’t whatever I might find on Netflix, something I knew I would enjoy after a day spent on taxes. My Hitchcock collection was at the top of the stack; the first movie in the collection was Saboteur.

I don’t know where the experts would rank Saboteur among Hitchcock’s films, as a matter of art. Not at the top, maybe. At least, it’s not one of the ones everyone knows: not Rear Window or Vertigo or The Man Who Knew Too Much, to name the films whose restoration in the 1980s led to a kind of re-popularization of the director.1 But what’s popular, and undoubtedly what we think of as meaningful, varies with the age - with the zeitgeist, if you want to use the $1.50 word. I don’t know if Saboteur really spoke to people in the ’80s. It sure speaks to me now.

notes for nobody but myself is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The plot, without giving away too much - all of this happens in the first five minutes2: A fire breaks out in a defense plant during the war. A couple of the workers run to try to put out the flames, but it’s hopeless, and one is engulfed in the inferno. The other, his pal, immediately falls under suspicion and goes on the lam to try to clear his name.

Saboteur was written, and production began, while war raged in Europe, but before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Maybe for that reason it’s a film that obviously reflects its moment without being topical. The Turner Classic Movies article linked above says Hitchcock wanted to avoid his film being “too on the nose.” It was the right choice, keeping the film from being too much of a period piece, even as it displays the United States before the cusp of war and the social and technological revolution that war ushered in.

So there’s no reference to Germans or Japanese or Nazis, but plenty of talk of fascism. We’re treated to a lively debate among circus folk that sets fascism and democracy in opposition to each other, the debate being resolved by a majority vote that the organizer insists upon as the principled (non-fascist) way of handling matters. It feels dated and naïve in early 2025, when whatever version of democracy we’re currently living in seems more like fascism’s handmaiden than its opposition. But then, the circus folk are ostentatiously naïve people, out of time even in that pre-war time.

Hitchcock and company walk a fine line in that respect. The folks that alleged saboteur Barry Kane encounters while on the run: emblems of homespun wisdom, or just rubes? Before meeting the circus troupe, Kane spends a few minutes with a kindly fellow named Philip Martin, who is a direct descendant of the blind cottager from Bride of Frankenstein. Really, the entire scene is lifted almost moment for moment: Martin, likewise blind, welcomes Kane in, plays music for him, offers him food, espouses the wisdom of the ages. Even the way the characters clasp hands is the same. One imagines Jimmy Whale seething at the artistic larceny.

The wisdom of Bride of Frankenstein’s blind cottager is religious; he kneels and prays with the monster. Philip Martin’s wisdom is drawn from the scriptures of the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. When his niece Patricia shows up and wants to hand Kane over to the police, telling him “it’s your duty as an American citizen,” he replies:

It is my duty as an American citizen to believe a man innocent until he’s been proved guilty. Pat, don’t tell me about my duty, it makes you sound stuffy. Besides, I have my own ideas about my duties as a citizen. They sometimes involve disregarding the law.

Told that the police said Kane was dangerous, Martin says, “I’m sure they did. How could they be heroes if he were harmless?” And he asks her, most resonantly: “Are you frightened, Pat? Is that what makes you so cruel?”

Indeed. Is that what makes us so cruel?

Martin plays a piece by Delius, remarks that he composes himself, speaks wittily in a voice that actor Vaughan Glaser surely didn’t learn growing up in Cleveland. Living in the woods though he may, he’s no rube. Or, being no rube, he chooses to live in the woods, where his attitude about the law doesn’t conflict quite so much with his neighbors’. When he first meets Kane, Martin tells him that he has always thought hitchhiking is “the best way to learn about this country - and the surest test of the American heart.” Homespun, perhaps. Or perhaps the American heart may not pass that test.

Later, Kane encounters the group of Nazis - again, not called thus - behind the fire at the airplane plant. Eventually he’s hauled before their apparent leader for a conversation about how the world works.

Nazi: You seem to have a soft spot for that young girl. You can’t afford to make yourself that vulnerable - not when you’re out trying to save your country.

Kane: Why is it that you sneer every time you refer to this country? You seem to have done pretty well here, I don’t get it.

Nazi: No, you wouldn’t, you’re one of the ardent believers, the good Americans, oh there’s millions like you. People that plod along without asking questions. I hate to use the word stupid but it seems to be the only one that applies. The Great Masses. The Moron Millions. Well there are a few of us who are unwilling to just troop along. A few of us who are clever enough to see that there’s much more to be done than just live small, complacent lives. A few of us in America who desire a more profitable type of government. When you think about it, Mr. Kane, the competence of totalitarian nations is much higher than ours. They get things done.

Kane: Yeah. They get things done….

(The scene devolves from there into fairly standard wartime propaganda. Less would probably have been more, but there were the War Department censors to placate.)3

Spend any amount of time wandering through social media in early 2025 and you’ll find a version of the argument made by Hitchcock’s Nazi. The United States is weak because of rules, rights, due processes … you know the list, and I don’t particularly feel like reciting it here.

There’s a puzzle at the end of Saboteur, regarding whether the Nazis’ last plot succeeds or not. I’ll not say much about it, other than that my conclusion is that the plot does succeed - perhaps it would have been another problem with the War Department to be more explicit about that. If so - if the second image, and the slight smile on the face of our saboteur, reflect the actual outcome, it runs rather contrary to convention, even for Hitchcock. I think - this is entirely a choice, to be clear - I think the message is that the Nazis’ success is tactical: one blow in an line of battles with no apparent end. And that the ultimate victory will be be won by the spirit in the American heart, so clumsily expressed by Kane as he faces his nemesis.

Early in 2025, it feels as though the fascists have since learned that lesson. The American heart is full of rage, of selfishness, of fear and the cruelty that goes along with it. You know this list, too. Watching Kane traverse the country warning anyone who might listen about the existence of a fifth column feels quaint on days when the government’s sole intention is to disregard the law, when insisting on abiding by the law is the revolutionary act. Saboteur is a film for our time, reminding how much the times have changed since it was made.

Hitchcock, or maybe the studio but probably Hitchcock, was really good at naming films, telling you everything and nothing in a few words. That said, it’s also the case that he titled one film “Saboteur” and another one “Sabotage” and I’m forever confusing them. ↩

Along with his economy of language in titling films, Hitchcock tended to employ a great deal of economy in getting us into the plot. ↩

Otto Kruger plays the villain perfectly: calm and controlled, toying with his mouse as long as it pleases him and dispatching him as soon as it no longer does. Robert Cummings isn’t quite up to his counterpart; he rather plays an actor playing a passionate naïf, not the naïf himself. Apparently they wanted Gary Cooper for the role, but Cooper felt he had better things to do. I’m not sure Cooper would have been right either. ↩