talent and execution

Some housekeeping: You may see, in the near future, an option to become a paid subscriber to notes for nobody but myself. To be honest, I’m not really sure how that’s going to work. If you choose to subscribe, I’ll be forever grateful, and it might at some point help me spend more time writing and less time doing other things. At present and for the foreseeable future, however, I don’t have any plans to require payments. Any amount you contribute will be a gift.

As always, thank you for being here and reading.

Merlin Olsen was one of the greatest defensive linemen ever to play football - one of the “Fearsome Foursome” for the Los Angeles Rams, he was a Pro Bowl selection 14 straight years and is a member of the pro football Hall of Fame. After retiring as a player, he had a more understated but equally successful career as a television analyst, working alongside and providing counterpoint to the exuberant Dick Enberg. Olsen would patiently explain plays and strategy with a calm manner that was utterly at odds with the way he played.

Often when a hall-of-famer turns to the broadcast booth he falls flat. The Reds’ second baseman Joe Morgan was legendarily bad at analysis, in part because he never seemed to grasp that mere mortals couldn’t do everything he could. They couldn’t field like him, hit like him, run like him; especially, they couldn’t see the game as quickly as he could. In other cases, the greats’ sense of their own greatness gets in their way. What they know in their hearts clouds their ability to see what’s in front of them.

Olsen, though, excelled at football analysis. I can recall one game where the outcome was defying expectations. Enberg asked him whether the best team was winning. It might have been a Super Bowl or a playoff game, one where that question mattered a little more. Olsen rebuffed the question. “All athletic competition,” he said, “is a combination of talent and execution.”

I suppose that’s just a more erudite formulation of the old saw, “that’s why they play the games,” but I like the Olsen’s phrasing better. It’s not only that the best team doesn’t always win - it’s that there is no “best” team distinct from the way it performs.

As you likely know, the Hated Yankees won the recent American League Championship Series going away. The Kakoola Reapers against the Port Ruppert Mundys, the latter disguised as Cleveland’s Guardians. The Gas-House Gorillas vs. the Tea Totallers, if you prefer your analogies animated. Nothing about the outcome was especially surprising, even as it was demoralizing in the way that losing to the Yankees always is. Cleveland would keep a game close, work its way to the eighth or ninth inning tied or within a run or two. And then: Wham! - a homah. Wham! - another homah. Wham! wham! wham! …

At one point in the deciding fifth game, my friend Lance turned to me and said, “It’s pretty clear the Yankees are the better team.” In truth, that was the way it had seemed all season - the Guardians would come up against the Yankees, or the Dodgers, or the Phillies, against teams with lineups stacked with one masher after another. Guys like Aaron Judge, certain to be this year’s MVP, and then Juan Soto, who would be MVP in any other year, and then Giancarlo Stanton, a shadow of the player the Yankees first traded for but still capable of hitting a fastball to the moon. And even when Cleveland won - they were 2-4 against the Yankees, 1-4 against the Astros, the two other division winners in the American League - you had the feeling it was by sleight of hand; by being cleverer, not stronger. Because time and chance happeneth to them all. Somehow the Guardians managed to win two out of three against the Phillies, but the Phils scored more in their one win than Cleveland did in all three games.

So Lance was right that Cleveland was in no way the more talented team. Against the Dodgers’ Ohtani, Betts, and Freeman, they put up José Ramírez and … other guys.

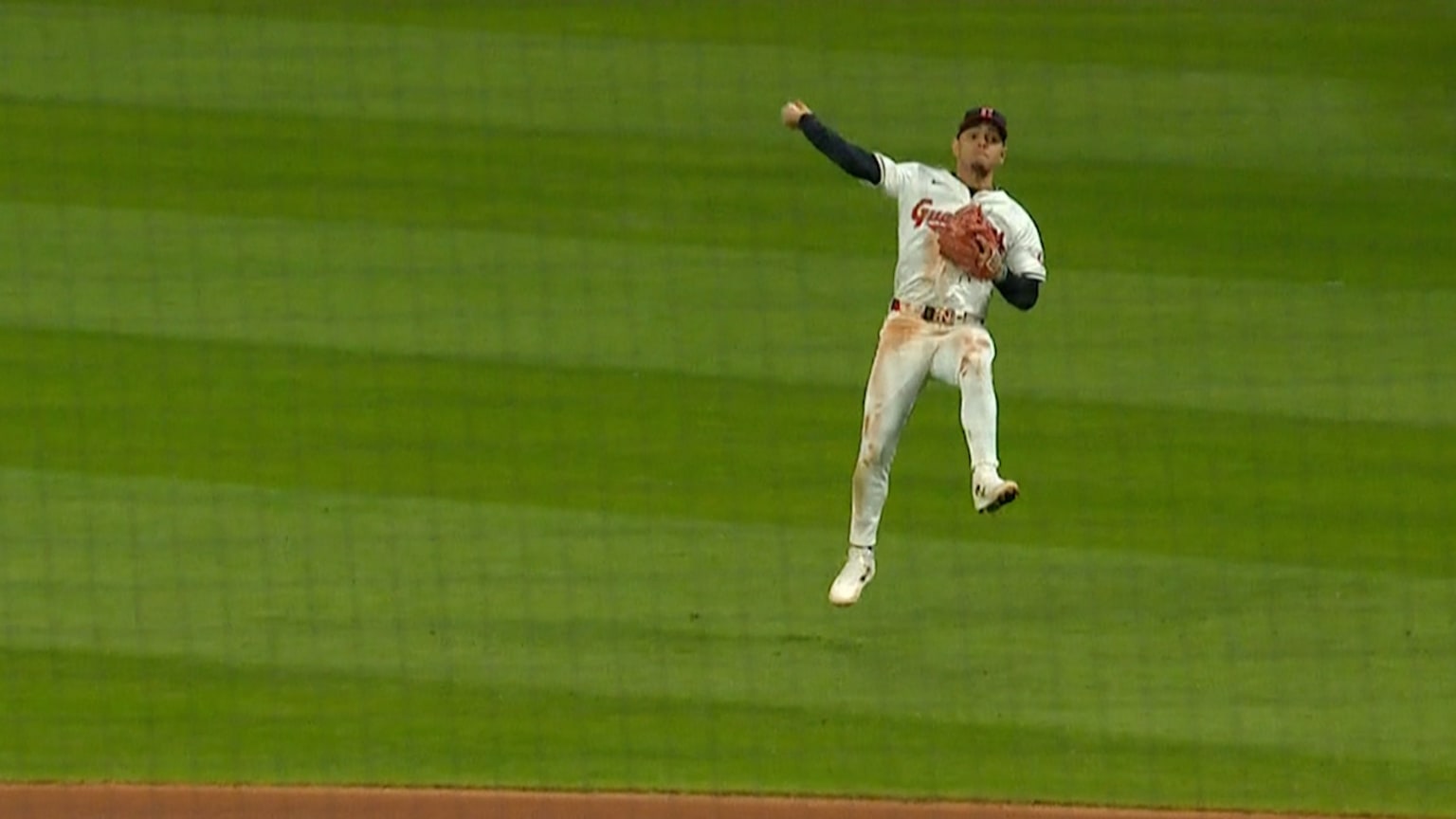

They won with execution. I hear about the “beautiful game” that Argentina’s national teams play, and I can’t see it because I don’t know enough about soccer. Well, I know something about baseball, and the Guardians played a beautiful game all summer, even through a midsummer stretch when they struggled to put runs on the board. Ramírez especially: He has an uncanny ability to see the entire field; to spot the runner straying off base and quickly throw behind him, or to see that the third baseman is half a step too far from the bag and with a sudden burst of speed be diving under a tag, wagging his index finger when someone dares to claim he might have been tagged out. On a long hit to the outfield, second baseman Andrés Giménez, the finest defender in all of baseball, somehow knows exactly where to place himself and exactly where home plate is behind him, catching and throwing like lightning, even before he can see his target, to put out a surprised runner. On such a play, the Cleveland outfield had a mantra: “Get the ball to Gimi.” A joy to watch.

The Guardians would not, though, even when they were running away with the division race in April and May, strike fear in anyone’s hearts. You’d look up and down the opposing team’s lineup and wonder, how are we going to keep up with these guys?

The only way for the Guardians to keep up with the Yankees in the postseason would have been to play perfect baseball. I don’t mean impossible baseball. I don’t mean that suddenly Ben Lively, one of the pitchers who saved the Guardians’ season through grit and guile, would suddenly be cranking 103-mph fastballs past Judge and Soto. But perfect baseball they way they can play it, the way they might play it. The way they did at times this summer.

As a kid following less-capable Cleveland teams, I would look forward to an upcoming season and tell myself, “if this happens, and if this happens.…” If Andre Thornton can hit 30 home runs again… (he did). If Joe Charboneau can recover from his back problems… (he did not). If Miguel Diloné hits .340 again… (he never came close). After a couple years of that, I figured out that the more ifs you had, the less likely you were to find yourself atop the standings.

There were a lot of those ifs going into ALCS against New York. Some of them turned to gold. In Game 3, the one that Cleveland won, Giménez nabbed a ball no second baseman has any business getting to, keeping the game close enough for Jhonkensy “Big Christmas” Noel to rescue the Guards in the bottom of the ninth. In Game 5, Gimi was at it again, cutting down Gleyber Torres as he tried to score in the top of the first.

Mostly, though, the Guardians were finding themselves in games where they needed a savior. The more ifs, the less likely is success, and likewise the fewer times you find yourself needing heroics in the bottom of the ninth, the better. Those were the circumstances that faced the Guardians each night against the Yanks. One-for-five in that situation is actually a pretty good outcome; the problem in that ratio is not the one but the five.

Most confounding about the series, about the Guardians’ whole postseason, was the man who didn’t execute, the man who, alongside Ramírez, was the most sure bet on the roster. Closer Emmanuel Clase had put up a season for the ages: 4 wins, 2 losses, an earned run average of 0.60, a league-leading 47 saves. He allowed five earned runs all season - as dominant a performance as the game has seen in twenty years. And against that 5 earned runs in 74 regular season innings, Clase allowed eight earned runs in eight postseason innings against the Tigers and the Yankees.

As the closer, Clase pitches only when the game is on the line. Twice he failed; only the Big Christmas miracle saved one of those games for the Guardians. (In the fifth and final game, he preserved a tie score, only to see his teammate Hunter Gaddis - 6-3 in the regular season with a 1.57 ERA; the star in almost any other bullpen - allow a three run homer to Juan Soto that for all intents closed the door on the season.)

Before the fifth game, the sportswriter Molly Knight asked in her weekly zoom with subscribers, “What’s up with Clase? Do the Yankees have something on him?”

“What’s there to have on him?” I replied. “You know what’s coming - a 101-mile-per-hour cutter. They’re just hitting it.”

People in the unsavory corners of the internet are probably debating and speculating. Was he tired? Was it the pressure of the postseason? Of facing the Yankees and their grim lineup of reapers?

I don’t know. Baseball is a combination of talent and execution.

The other thing - I’m sure there are many other things, but to name one - the other thing people were talking about in the aftermath of the Guardians’ were the decisions of manager Steven Vogt, in his first year on the job, following the retirement1 of Terry Francona. I haven’t looked, but I imagine the record of first-year managers in the World Series is not good. Beyond that, the sample is small. First year managers rarely make it to the World Series, partly as a matter of experience and partly because they more typically are replacing a guy who was fired the year before.

Unquestionably, at times Vogt’s decisions made it look like he was managing tight, even if it wasn’t displayed in his taciturn expression. He pulled his his starters so early that the players’ joke about when he was going to go to Cleveland’s dominant bullpen - in the third ining? the second? - became reality. He seemed to be giving into an instinct to overmanage under the microscope of the postseason.

There are smaller decisions, of course - whether to pinch hit, whether to steal a base or bunt - but inevitably, the world judges a manager’s performance by when he walks to the mound, and whom he calls on when he does. It’s a sucker’s game. Make that walk too early and you’re Captain Hook, bringing in a cold arm from the pen to pitch under pressure. Let it ride one batter too long, and anyone could see your man was tiring. One way or another, it’s going to blow up on you. Time and chance, again.

Or, if you will, talent and execution again. I don’t particularly understand the choice to use Ben Lively so sparingly; Cleveland’s second-best starter all year was relegated to mop-up role in the postseason. (That plainly wasn’t Vogt’s decision alone.) Otherwise, though, Vogt leaned on talent, time and again. Should he have left Bibee to face Giancarlo Stanton in the 6th inning of Game 5? Easy to say no, now. Should he have brought in a weary Clase in the 8th? Again, easy in the aftermath.

Can you ever say a manager has made the right decision when it comes out wrong? In the press room, afterward, you’ll hear more cliches. He was our guy all year. I’d make that decision again, 100 times out of 100. None of those quite answer the question. I want to say Vogt made the right decision, his team just didn’t execute. Then again, if his team didn’t execute, how could it have been the right decision?

That conundrum lives alongside how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, or maybe, “How many Angels can be hall-of-famers and not make the postseason?” As a wiser man than me once said, the race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong. But that’s the way to bet.

Since rescinded; Francona is headed to Cincinnati to lead the Reds next year. Good news, that: the game is better with Francona in it, and the game is better when the Reds are good. ↩