tension in the sail

making meaning

One morning, sitting in Falconworks’ office overlooking the housing project dumpsters, I got a call, or an email - I don’t know how it came. “We want to work with you on a theater project.”

“We” was the Red Hook Community Justice Center. Back up a minute. Red Hook is a neighborhood in Brooklyn that sits on the waterfront - so much so that it’s literally the neighborhood described in On the Waterfront. (The original screenplay was written by Arthur Miller and was titled either The Hook or Red Hook. The latter would aptly have alluded to communism, the way Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest explicitly did. Given Elia Kazan’s politics, that obviously wasn’t going to fly.)

Red Hook was a working-class neighborhood from the start, a rough-and-tumble one, full of longshoremen who coulda been contenders. (Several decades ago, the area called “Red Hook” was considerably larger, and what is now called Red Hook was “the Point.” Once I met a fellow in a bar - his name, he said, was Victory - whose mother, he said, used to scold him for going to the Point. He was going to get himself in trouble there, she said. Probably so, although she may not have imagined exactly the sort of trouble he was going to get into.)

Red Hook was home to a Hooverville in the thirties, and in order to clean that up, the city constructed two housing projects, which together were the largest in Brooklyn. A bit later Robert Moses came along with the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and severed the Point from the rest of Red Hook. For reasons too numerous to describe here, the neighborhood’s economy declined over the subsequent 40 years. Last Exit to Brooklyn was set in Red Hook, and that novel and film don’t paint a portrait of life in an alabaster city.

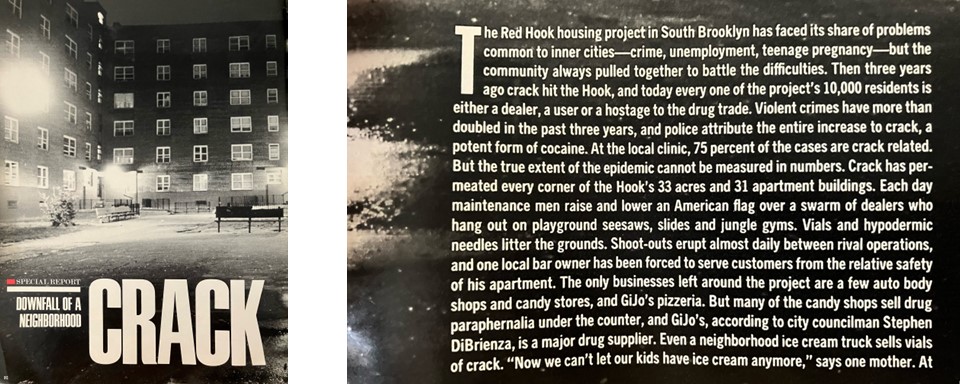

By 1988 the nabe had reached the point that Life Magazine called it “the crack capital of America.”

In 1992, the principal of one of Red Hook’s two elementary schools, Patrick Daly, was killed in the midst of a gun battle while he was looking for a missing student.

(I’ve recited elements of this history many times. In our early grant applications, the version was “we’re making theater in an economically depressed neighborhood, you should support us.” In the later applications, it became “gentrification hasn’t solved these problems for the folks who lived here before, you should support us.”)

Eventually, enter the Red Hook Community Justice Center in 2000. The JC bills itself as “the nation's first multi-jurisdictional community court,” encompassing civil, family, and criminal courts under the same roof, in the same courtroom, with the same judge. That undersells things a bit. Besides a unified court they offered housing services and a youth court - staffed by teens, with actual jurisdictional powers - and after a while a “peacemaking” program in restorative justice that I was honored to be a part of. That their work is revolutionary says more about our society than the Justice Center.

When Falconworks arrived in Red Hook, the JC also had a program training teens to be peer health educators, focused on reproductive health and substance abuse mitigation. That was how we met the folks at the Justice Center; Pink, our artistic director, was going around our new neighborhood asking what the community needed or wanted from a theater company. At that moment it wasn’t obvious that Chekhov was going to be the answer. (Looking at our box office receipts, it wasn’t obvious after the run, either.) The answer from Erin, who managed the health education program, was “let’s use theater to help communicate health information.” Out of those conversations, our Off the Hook program was born.

So we formed a relationship with the Justice Center, which extended to taking on some of their Americorps interns - another of their offerings - and to using some extra space they had in the Red Hook housing project as our offices for many years. And thus it wasn’t unexpected to get a call from someone over there about wanting to do something together.

“We want to work with you on a theater project.”

The call came from Amy Roza, whom I mostly knew as Erin’s boss, and who in the fullness of her career had a title something like Director of Community Programs. She was young and energetic, inviting, quick to smile, eager to build things. I wasn’t as young, and was a little bit lost, having taken a buyout from my corporate employer and having found myself running a theater company, which had never been my plan. But to use somebody else’s phrase, “Men plan; God laughs.”

I walked the thousand feet or so across a corner of Coffey Park, then the block down Richards Street and halfway up Visitation Place to the Justice Center. Their building is an old Catholic school, on the back side of the block where Red Hook’s massive, sparsely attended Visitation Church sits. (Directly behind the Justice Center is the former school’s cafa-gym-atorium, a hall that could easily seat 600 with a stage and a balcony and plenty of room in the basement - was the subject of innumerable pipe dreams. It needed, conservatively, $10 million in work, and the church somehow imagined the building was going to be their meal ticket besides, so our fantasies about what we could do there remained just that.)

Amy and I met in her office. The vibe in that room - in marked contrast to the lobby full of court officers and metal detectors, lit by fluorescent bulbs, smelling of floor cleaner - was one hundred percent California flower power. Spider plants, tchotchkes, personal photos, posters combining inspiration and past achievements. More than that, Amy, with a constant smile, long hair with maybe one braid, a nose ring, a laugh like silver coins.

Amy’s remit included overseeing the Justice Center’s Youth Court, a body consisting of teens and young adults who would serve as tribunal adjudicating low level infractions by other teens, things like graffiti, vandalism, fare evasion, and so on. She laid out the problem: the Youth Court had been seeing more and more referrals of cases involving a police interaction that should have been nothing. Something that starts with a police asking a young person, where you going?

I will pause here to observe there are a hundred problems with that scenario, which more or less boil down to, most of the time it’s none of the police’s everloving business where the kid is going, and a neighborhood like Red Hook, because of its long and checkered history, tends to be heavily overpoliced, or at least policed in all the wrong ways. I could go on at length about this; other people have. Amy was well aware of that, and I’m sure we discussed it, at least briefly. (I, having spent less time grappling with issues of criminal justice, was probably less well aware of it. We’ll get to that.)

Nevertheless, the consequences were real. Young people were being stopped, often for no good or defensible reason. Those stopped were reacting predictably, being young people. The police, according to their own nature, got defensively aggressive. And the next thing you knew, a kid was in front of the judge on charges of resisting arrest and truancy and maybe carrying some form of contraband, and, in the words of Robert Mitchum, “mokery with intent to gawk.”1 Or in my words, insisting on their rights.

You don’t have to be young to be irritated and self-righteous and defensive and scared when police stop you for no reason. Many years later, I was walking more or less that same path out of the housing project over toward the “back” of Red Hook, the part with single-family homes and increasingly bougie restaurants. A car rolled the wrong way up my street, Pioneer Street, and the driver leaned out the window and said, “Can I ask you a question?”

“You’re going the wrong way,” I said.

“I know,” he said, and I looked again at the unfashionable sedan and realized they were plainclothesmen. We proceeded to have a discussion about where I’d been, what I was doing there, where I was going. I told them and they asked me for proof. I spent a quick moment considering my rights and principles and how entertaining it would have been to appear at the Community Justice Center before Judge Calabrese. The judge was a personal friend and a supporter of our work and would have known exactly why I had been in the housing projects, and that it wasn’t for what the officers suspected this white guy was doing. In my rapid imagining of the scene he would have told the officers what for. All of that on one side; on the other, the unpleasant if educational experience of the lockup in Brooklyn and the possibility of losing the job I had newly taken. So I showed them the proof, throwing in a couple of digs that would have gotten me a proper beat-down if I’d been twenty years younger and a different color.

But I was twenty years older, and able to game out the consequences in a few seconds. The kids Amy was concerned about, not so much. They would mouth off to the cops, maybe as little as asking “Why?” and end up at best with a missed day of school, at worst with a record. Amy’s idea was to figure out how to stop the problem by not letting it start in the first place. Somehow, it would involve police officers and young people making theater together.

She had gotten the idea by reading about a theater artist in Chicago, Sharon Evans, who had undertaken a similar idea. Get some police and young people in a room together. Let them play around together, with a common goal. Hopefully, break down stereotypes that participants on each side, cops and kids, have of the folks on the other, and maybe that will virally change the dynamic over time.

It sounds a bit Underwear Gnomes when I write it that way:

- Cops and kids do theater together

- ?

- Harmony

I probably thought it sounded a little Underwear Gnomes at the time. But two things were going on in my head. The first was - bias alert - I was naïve about the police, and thought we could change a little part of the world. Twenty years later, I don’t know if I think the police can be reformed. The truest thing I’ve ever read about the cops is that the problem with police work is that it demands the best sort of person, and there’s nothing in it to attract the best sort of person.2

My sense is that the foremost values of the typical police department, certainly the NYPD, is to resist ceding power. Being on good relations with the community is ceding power, which sounds like a warped worldview, and is, but it explains a huge number of the dysfunctions of modern police forces, large and small.

I’m not sure if, twenty years older and more worldly, if not wiser, I would undertake this project again. I might say to Amy, “Nah, let’s burn down the 76 Precinct instead.” I’m glad I didn’t; we didn’t do much in the way of harm, probably some good, and I learned a lot from the experience - enough that I think it’s worth writing about here. Sometimes standing on principle isn’t the right course.

The second thing going on in my head was, I had a theater company to run. A nascent one, which basically had one small kids’ theater program, and which didn’t seem sustainable at that size. Again, with the experience of twenty years I might see things differently now, but at the time it seemed clear that the way to make the thing work was to grow, to win more grants and earn3 more money and have more to spread around to pay the artistic director and the managing director and some staff. And the way to grow is to start doing new programs.

(Pause to note: there is basically no such thing as venture capital in the not-for-profit world, certainly not in the arts. You have to do a thing first, scratching together whatever funds you can, and then hope that a couple years later some nice rich person will decide it was worth doing, and give you a quarter of the money it takes to do it, which itself is half the money it ought to take to do it. And they’ll be called a philanthropist, and you’ll be called a dreamer.)

So whatever doubts I had, multiplied by whatever naïveté I had, led me to sit in Amy’s office and discuss with her how a theater project involving cops and kids would work.

The first few meetings were nothing but sunshine. Amy had a warm and light spirit. Her office was a refuge. There was nothing we couldn’t do. We watched a video sent by the group in Chicago and talked about it, and felt inspired by it. We talked about how revolutionary this would be. I’m sure, if we didn’t talk about it, we both thought about how we and our organizations would bask in the reflected glory of this program, which would obviously generate some publicity. (There were numerous clippings and news reports from Chicago.) It was a bit like heading out on a vacation: as you drive off, you’re certain that the weather will be perfect and everyone will smile constantly as you drink margaritas on the deck.

So what do you do when you find the beach house you’ve rented is not quite as spacious as the pictures, and one of you has different ideas about what “relaxing” means? What do you do when the reality of theater and the reality of criminal justice are at odds.

Obviously, one thing you can do is pack it in. At times, in the 20-year course of running our theater company, any number of opportunities to do just that presented themselves; any number of people, up to and including our artistic director, suggested that as an option. In the end, whether through stubbornness or complacency, we plugged away until there wasn’t any other choice. With respect to cops and kids, as we started to call the program, I had a theater company to build, and Amy had both a reputation to build and a mission to create a better world. So no, we didn’t pack it in.

Another thing you can do is to fight it out and see who wins. I probably tried to do more of this than Amy. I’m sure I did more of this than Amy. I was recently coming off a six-year stint at a major global bank where the predominant form of engagement was arguing. Along with dirty tricks: undermining colleagues, not inviting key counterparts to meetings, stealing credit. As much as I tried to keep my head down and work, being in that environment exacts a cost. The only thing saved me was that I had left the place because I was tired of bringing an angry face home to my spouse at the end of the day.

Working with Amy I learned a better way. I like to think we learned a better way. I don’t know that, maybe her experience with me was routine. I tried to get in touch with her to talk about this, what her experience was, but it’s been more than 15 years and a couple of moves and new jobs for both of us. I would like to think, though, that she got something out of spending hours with me in the sanctuary of her office, debating and working through details.

Mostly, our differences centered on getting the demands of artistic expression - more specifically, of the Falconworks Theater Company’s bottom-up approach to artistic expression - to mesh with the police’s desire for order and respect. Amy was very much a realist in attempting to square this circle; I was, somewhat contrary to my nature, a visionary. She knew, instinctively - if she wasn’t also being reminded of it by her bosses - that the NYPD brass were going to take considerable convincing. If we could get them on board - well, Cops and Kids wasn’t going to be easy, but it was going to be possible. Without them, forget it.

So we debated everything. When. How long. How often. What form of theater we would employ. How we would describe this to potential participants (and their commanding officers). What we would do in the workshops. What kind of public performance we would have.

As well as just the practical questions: How were we going to pay for this? Where would it take place? Who was going to find these police officers and young people? Would we pay them? The Justice Center’s model was to pay program participants for everything, a defensible idea in a neighborhood like Red Hook, but a little contrary to our sense that we were providing training that itself was compensation.

Even the name of this thing. “Cops and Kids” clearly wasn’t the answer.4 I don’t remember this being an especially heated debate, but we were well into offering the program before we settled on anything, which ended up being the prosaically descriptive Police-Teen Theater Project.

It was a year of conversations, a year of struggle, to be honest. I would leave Amy’s office drained. And, I would leave her office inspired. It took me a while to figure out that strange combination of emotions - I’m still, in the spirit of this backward-looking blog, this grieving process, understanding it. The new experience was people working together in good faith - let me repeat that, in good faith - to come to an agreement.

To be fair, that happens a lot in the theater. Not always; sometimes you get an actor who just doesn’t play well with others, or decides to be in their own personal production of a play, contrary to everyone else’s. Sometimes you work it out, sometimes you tolerate it until it resolves itself, sometimes you see opening night approaching like an oncoming train and brace for impact. In the worst cases, you step in and make a change in the most gentle but firm way you can manage: “What if we try this?” with direct eye contact, held perhaps a moment longer than necessary.

But most of the time in the performing arts, everyone shares the goal. That is less true in corporate America, and I suppose I had spent enough time sitting in offices fighting for turf that it was strange to find myself sitting across the room from someone who wanted not just to come to agreement, but to achieve the best of all possible outcomes. It was equally hard to forestall my instinct to battle, and to be comfortable in our disagreements. To “sit with it,” as the kids say.

Somewhere along the way, I saw how much progress we were making. Somewhere along the way, I saw that listening to Amy and seeing her point of view, and proposing my own, and coexisting in our at times opposing worldviews, the practical and the visionary, was making space for impossible outcomes. And I coined the phrase I referred to in passing previously:

Tension in the sail moves the boat forward.

The boat wants to stand still. The wind wants to pass over it. If you leave the sail to its own devices, nothing happens. But if you keep the two in balance, with a careful hold on the lines, you make progress. And with the right crew and the right conditions, magic happens on the water. Not only does the boat move: the boat can sail faster than the wind.

I have always thought that this is the corniest of the many corny expressions I devised during my theater days. And yet, for me, it held the key to keeping at it. It enabled me to sit in a suit through sober meetings with risk-averse police lieutenants. More than that: not just nodding and looking serious, but actually working to achieve their objectives, even when I disagreed with them.

I’m reflecting now that, whatever conflicts Amy and I might have been trying to hash out between us, we were each doing the same in our own organizations as well. I was taking what Amy and I were grappling with back to our artistic director, knowing that the AD would have been just as happy to jettison the whole project. And then I would carry the AD’s suggestions and objections back to Amy so we could work them out.

Equally, Amy, more than I, knew the challenges involved in getting the court and the cops on board. The Justice Center, in all its work, lived a contradiction. The justice system as it has evolved, over not just the length of American history but going back to the Magna Carta or Charlemagne or probably Hammurabi, has a well-developed set of procedures, whose most important principle is that of order. Not just being the mechanism that maintains order outside the walls of the courthouse, but proceeding according to its own set of customs and roles and attitudes.

Insiders know exactly how this is supposed to work; it’s second nature to them. Outsiders see sausage being made. Or worse, are simply mystified, particularly if they happen to be a litigant or a defendant and the lawyers and other officers of the court are speaking a foreign language and moving at what appears to be light speed. (As part of the JC’s Peacemaking training, we attended an hour or so in the court. Afterward, the attorney who was in charge of our training said, “Isn’t it wonderful, how calm and humane everything is.” Let’s just say that’s not the impression I had.)

So the engine driving the Justice Center was a court, mostly a criminal court, where although the law may presume innocence, the functions of the court imply the opposite. And surrounding this court - almost literally surrounding it, in the architecture of the building - were a group of people dedicated to systemic change which necessarily included altering the machinery of the court - and the police, and the district attorney, among others. Those people’s inclination was to say in response, “We’ve done it this way since Hammurabi.”

Amy lived in those conflicts daily, while I was just being introduced to them. I would say “why can’t we just …,” wanting nothing more than to get to OK and go home. She never let me do that, and eventually I grew to appreciate how critical that was, both for the project and for my own growth working in the arts.

So Amy, too, embraced the tension in the sail. I don’t know the sidebars she may have had with her management or with the police, and how much of a battle she was fighting. What I saw was that she trusted us on the theater side to pursue the shared ends with good faith and care. Over time I learned that however patient and kind Amy was, she had a backbone of steel. It became my mandate to learn to do the same for her.

It took over a year of those meetings and debates and quiet frustration to go from Amy’s first phone call to our actual launch in the fall of 2007. Apart from wind and a crew keeping hold of the lines, a sailor needs patience.

In the end, the tension we held between us in the sail of our project enabled us not only to get to OK, not only to “Yes,” but to getting to Better. In the end, it made the project not only possible, but worth doing.

We launched, if I remember correctly, with eight police officers and eight teenagers from a few nearby neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Amy’s insistence on rectitude made it possible to get the three precinct captains on board, who then allowed us to attend early morning or afternoon roll calls to pitch our project to mostly dubious men and women in blue. (Side note: NYPD precinct houses in 2007, and probably today, had a few more computers but otherwise looked basically unchanged from the days of Barney Miller. The 76 still had a chalkboard that they used to track the comings and goings of officers.)

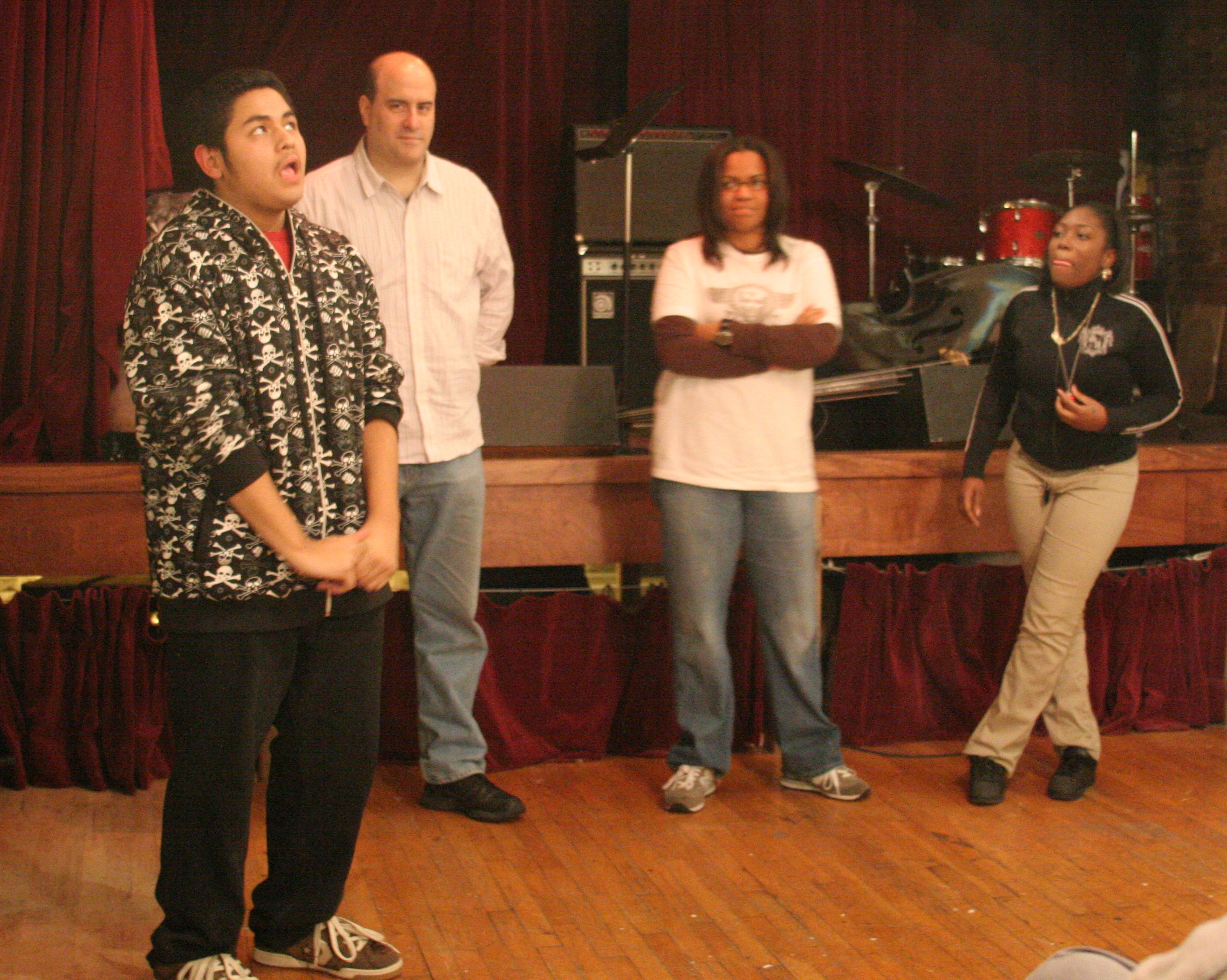

We had agreed that rather than developing with some kind of didactic, deadly earnest play about police and kids, like the Police-Teen Link in Chicago, we would do improvisational theater. Improv was the risky choice; the safe route would have been to develop that earnest-but-deadly play, run it past everyone to make sure nothing would offend, make sure all the actors knew their lines, and bore the audience to tears. And that would merely have reinforced the existing dynamics: ceding control to authority; limiting young people to free movement only within carefully proscribed lines. With improv, on the other hand, everyone started on the same level; everyone was out there without a net. Everyone had to be equally brave and, more importantly, trust their partner to keep the scene moving. To say, “Yes-and” to each other.

We began with ten weeks of workshops in a local performance space. The leader was Melissa, an enthusiastic performer, playwright and teaching artist who was equally capable of cheerleading “yes-and” exercises and feigning nonchalance when an officer’s gun went sliding across the floor during one particularly energetic bit of scene work.

At the end of the series of workshops we sold out our first show, titled - with some trepidation, knowing that it might not delight the commanding officers who had blessed all this - “RIOT ACT.”

The project ran for three years. I write that with some disappointment - some guilt maybe. The part of me that is an artist wants to create things that last forever, but that isn’t the way the world works. Amy moved on to new projects; other staff supporting us at the Justice Center took new roles; our teaching artist Melissa went to Thailand. Having lost its champions, our project’s challenges overtook its rewards. Our wind, you might say, died.

Things lasting forever isn’t the way theater works, either. You spend months, years, preparing a show; you spend weeks rehearsing it; you spend hours performing it; then you clear the stage and you’re not sure it ever happened. (There’s a blog post in that, if I could think of a corny phrase to pair it with.) In the end, you take away the experience and hold onto it for the next time the phone rings and someone says, “We want to work with you ….”

“Crack: Downfall of a Neighborhood” from Life magazine, July 1988, p. 92

“Brooklyn Principal Shot to Death While Looking for Missing Pupil” from The New York Times, December 18, 1992, p. A1

Original “Riot Act” poster by Linden Elstran

The part where he says this starts at about 17:45. The whole interview is worth your while. ↩

I think this is a Dashiell Hammett quote. I can’t find it at the moment. ↩

The world of philanthropy divides income into “earned” and “unearned.” The notion of “unearned income” implies people are not earning grant money by doing the work every day. In reality, unearned income is generally the money philanthropists inherit from their parents. ↩

Let alone “Kops and Kids.” ↩