the persistence of memory

Having referred to Rutherford B. Hayes in passing in my last post, I figured I could pull this bit off the slag heap.

When I worked at Pomona College, one of the deans once commented on some change that was generating a conflagration amongst the student body. It might have been anything: painting a dorm a new color, changing the name of the Government department to the Politics department, maybe requiring submission of forms in triplicate before granting permission to paint a slogan on Walker Wall.

This dean observed that the institutional memory of the college was four years. If you could hold fast for that long regarding whatever change you were implementing to whatever hallowed tradition, you were home free. The student body would have turned over completely, and almost nobody on campus would remember anything different. (Obviously, some professors and staff would, but they tend to limit their protests a bit more than undergraduates).

A college has alumni, of course, a reality the dean glossed over in his argument. They’ll write angry letters to the college president or buttonhole an administrator at homecoming or threaten to withhold donations. Still, you can outlast them. Some years ago, Miami University made the long overdue decision to change the name of its sports teams from “Redskins” to “Red Hawks,” and the initial outcry was as predictable as it was dismaying. Over the years, however, people just got used to it. (Of course, many, perhaps a less vocal majority, were in favor of the change long before it happened).

It takes a bit longer with professional sports teams, whose fan bases are indoctrinated from the cradle and remain rabid until they move on, geographically or corporeally. (Perhaps longer.) My own beloved Cleveland Guardians, née Indians - in truth née Bronchos - finally got around to rebranding in 2022, after the killing of George Floyd and possibly a player revolt made keeping the old name untenable.

A few years later, people still wear their Indians gear to the ballpark, some because that’s the clothing they have, some holding on to memories of games with their fathers and mothers, some in anger. I sort of pity the last, but I also find they are fewer in number with each passing month. You still find them in the comments sections of the interwebs, insisting on referring to the team by its old name (and for that matter referring to the stadium as “the Jake” even though it hasn’t been Jacobs Field since 2007).

Joe Posnanski covered this topic better than I ever could. Read the comments there if you dare enter the mindset of the rear-guard.

But sports teams, too, have a kind of institutional memory, a community memory perhaps. Sooner or later, the majority of Cleveland fans will never have even known the team by the name Indians and will look aghast at its grinning, red-faced one-time mascot. And most of the rest will only dimly remember it, “Guardians” rolling off the tongue as easily and no more nonsensically than “Dodgers” or “Lakers” do for Los Angeles fans.

I started thinking about this topic while explaining to my niece and others present why I fantasize about running my car into the statue of Rutherford B. Hayes in my hometown.

Delaware, Ohio, is Hayes’s birthplace. The actual site of the house where he was born has for my entire life been a gas station, currently a BP, with only a granite marker the size and shape of an modest tombstone commemorating the spot. For the longest time, that tombstone and the name of the high school were the only acknowledgments Delaware accorded Hayes.

This was entirely appropriate. It’s a measure of Hayes’s reputation as a leader that, so far as I can tell, Delaware’s Rutherford B. Hayes High School is the only school in the United States named for the man. I have not checked, but I assume that is the record. Heck, there are at least two schools named for Millard Fillmore. Even Fremont, Ohio, where Hayes moved after law school and which is now home to the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums, has not seen fit to name a school after him.

(According to the available data, there are 98,577 schools in the United States. Back in 2016, I wondered whether the number of schools named for Donald Trump would be zero or 98,577. I suppose the jury is still out on that one.)

Anyway, until the last decade Hayes was at the top of my list of contenders for Worst President Ever. Admittedly, the competition is fierce, and further admittedly, I bear him special animosity because in addition to being among the poorest possible representatives for one’s hometown, Hayes is also the only U.S. president to have graduated from my alma mater Kenyon College. It is a further measure of his reputation that Kenyon has never seen fit to name a building after the man, or indeed, so far as I am aware, a classroom or academic award or flower bed.1

In case you are not up on your history: Hayes was a three-time governor of Ohio who ran for president in 1876 on the Republican ticket, against the Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York. The election was disputed, thanks to the stupid, slavery-sustaining electoral college, and allegations of fraudulent votes in Louisiana, South Carolina, and, you guessed it, Florida. With Tilden holding 184 votes, one less than he needed, and 20 votes in dispute, a brouhaha ensued, resembling one of those fights in a cartoon where the combatants disappear into a cloud of dust and fists and somehow one emerges the victor.

In this case, the victor was Hayes, and he gained victory by promising to remove federal troops from the southern states, where they had been enforcing Reconstruction and, to the extent possible, securing the rights of the formerly enslaved Black population of the South.

Let’s be honest here, Reconstruction was at best a half-measure, violently imposed. And let’s be further honest, Tilden and the Democrats of the era may have been a worse alternative. Nevertheless, judged we are for the things we have done and not in comparison to the worse things someone else might have done instead. Hayes brought the troops back north, Reconstruction ended, Jim Crow and the Klan rose up, and 150 years later we live in the aftermath.

So, I got to thinking, is there any plausible scenario in which Reconstruction might have succeeded, and the Black citizens of the United States would have been spared the evil done to them, still being done today? I obviously don’t know the answer to that question. As I grow older, though, I note with increasing frequency how short our lives are in comparison to the arc of history, and at the same time how events that seemed, when I was young, to have occurred eons apart, in reality happened practically on top of each other, practically on top of us today.

The past is never dead. It's not even past.

What is the institutional memory, the national memory, of this country’s racial divide? Is it eternal? Had Reconstruction lasted longer, would the people who had held slaves become fewer and fewer, and the children of people who had held slaves become fewer and fewer, until a large enough majority could only remember Blacks and whites enjoying something approaching equal rights? Such that the presence of enforcing troops would have been superfluous in deed as well as word? How much time would that have taken? Fifty years? Ninety? Again, I can’t possibly know the answer to that. Experience suggests it might have been worth trying.

What measures would it take, and for how long, to take up the effort to heal again? Experience suggests more than electing a Black president to two terms.

In any case, yeah, they can put that statue of Hayes in the same warehouse as the one of Nathan Bedford Forrest.

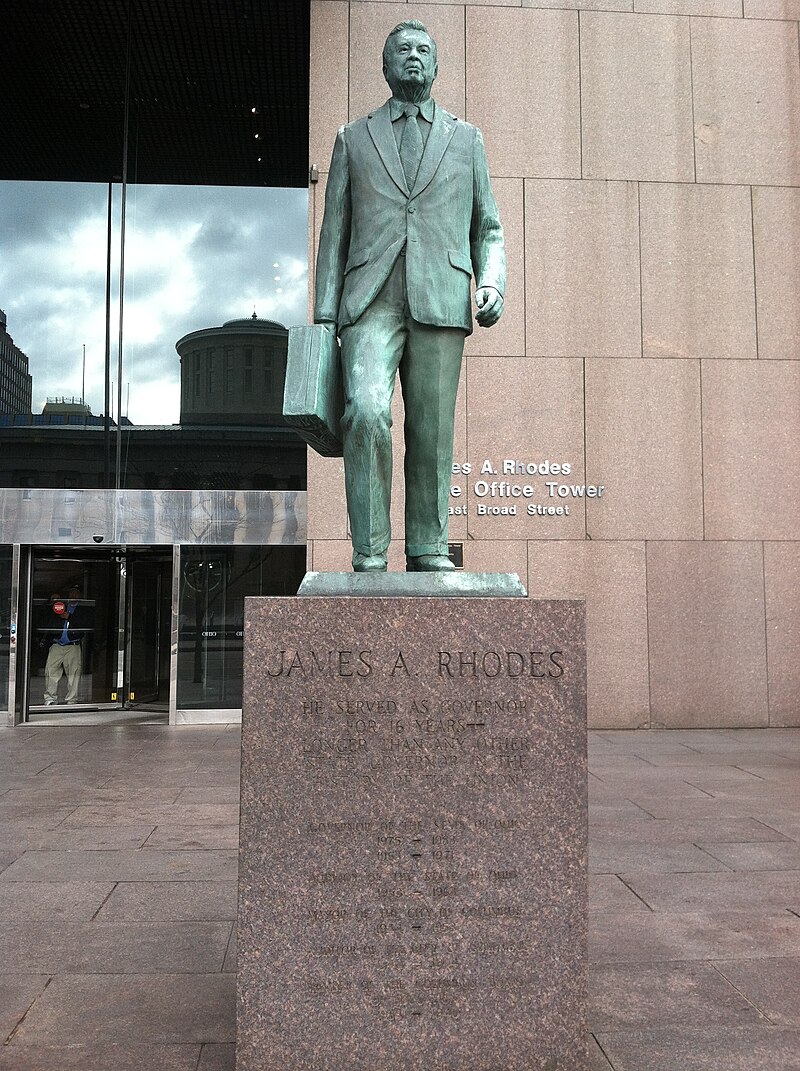

As for why I want specifically to drive a car into the statue of Hayes, I suppose I am just inspired by the man who drove his car into the statue of Big Jim Rhodes that stands in front of the Rhodes State Office Tower in Columbus.

He was not successful, and his act has been reduced in history to a single sentence in the statue’s Wikipedia page, the name of the vandal/revolutionary lost to time. I do not imagine my effort to take down Hayes would be more successful. Also, I don’t own a car. My niece and I speculated that a tank would be more effective. ↩↩

Photo of Hayes birthplace memorial by Tim Bash at https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/5862

Photo of James Rhodes statue by Anthony Castro at https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18724942