the struggle

The joy in putting stamps on envelopes and making phone calls and figuring out how to make a budget pencil out - or in running a major city.

I've been dealing with life in its various manifestations the last few weeks. My apologies. I'm late to the party with this one, but if I don't post it, it'll sit in my Drafts folder nagging at me. More regular posting coming soon, I promise.

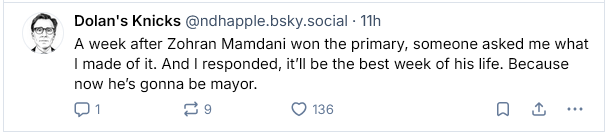

Over on Bluesky - where you should or should not follow me, I don’t know what you like to do - a journalist who mostly writes about New York City transportation posted the following a while back:

That isn’t wrong, and I'm not dunking on it here. First, it’s obviously intended to be humorous, and like all good humor is based in truth. Apart from that, it shows a journalist’s realism - part of me wants to say cynicism, but I’m holding back from that, because I don't think Nolan Hicks is especially cynical. You can see in his work that he wants things to get better and thinks things can be better. But it shows the eye of someone who has been watching city government for a long time, and has seen New York chew up more than one mayor. In the last year he’s looked at Mamdani with the kind of detached skepticism a reporter ought to have. (I never had it, which is part of why I didn’t stick in journalism. That, and they paid me, with my college loans coming due, $4.50 an hour. If anything, I think the pay is worse now.)

So: yeah, a chuckle, and "That’s kind of true." But only kind of.

Again: I am not dunking on Nolan Hicks. So I’ll say that a reader might look at Zohran Mamdani and see optimism, indeed naivete, and find in Hicks’s post support for the belief that Mamdani is going to get a quick and harsh lesson in realism, if not on Day 1, then in his first 180 days at City Hall. That will not be entirely wrong. And my experience tells me that that reader would be missing something.

I made theater in a low-income neighborhood for a lot of my life. What someone might call activist theater, or leftist theater, or more plainly, Theater of the Oppressed. You know this if you've been following along. In 18 years of keeping track, we never paid anyone a living wage and we never cleared $100,000 in revenues. My friend Katie, who worked at the Department of Cultural Affairs and knew about such things, once asked how much we spent on a set of workshops and the show that grew out of it, and when we told her, her eyes widened and she said "You guys are good ...."

That was just the way we worked, for better or worse.

At times it sucked. At times we asked, Why are we doing this again? Always, I asked myself, why am I working at a job I hate so I can do meaningful work? Why am I writing grant reports at 2:00 in the morning? Why can’t this stage have better wiring? Why can’t we have a toilet that flushes? Why can’t this funder see the good that we’re doing? Why aren’t we having to turn people away?

We decided to quit several times, only to lose our nerve. We never found the magic formula. Always, it was a struggle.

That word.

Making leftist theater, I found myself in the company of various stripes of leftists. And I may not quite be the kind of realist Nolan Hicks is, but even as an optimist I can be a bit of a skeptic. So I would go to meetings of various kinds, which sounds like I mean gathering in a basement somewhere plotting schemes, but actually just means brunch at somebody's house, or a workshop on grassroots fundraising, or drinks after a concert. People would talk. A certain type of leftist would talk about “The Struggle,” capital letters you know, and I would look at them a bit sideways. (Figuratively, I mean. Eh, probably literally; I have no poker face at all.)

Because there’s a certain type of person out there - I’m mostly familiar with people who want social justice, but it might be any sort of person I suppose - who locates a great deal of their self-image in being a fighter. A fighter against impossible odds. A fighter who sometimes seems less concerned with victory than with the personal rewards of combat.

One’s cartoon image might be that all progressives, all leftists, are that way. The ones who show up looking for microphones after some injustice occurs often seem to be that way.

My realism - let me use the word about myself: my cynicism - has kept me from being an especially good leftist. I do tend to want to fight (you should see my Bluesky posts about Feckless Chuck). But I’ve never wanted to fight because I like fighting; I want to fight because I want to win. And it’s that combination of things, my cynicism plus my easily accessible anger, times my insistence on winning, that often kept me from comprehending the joy in the work.

In the struggle. (Lower case.)

Eventually, if you go to enough Brunches with Leftists - and if that isn’t a suitable title for a talk-show parody on SNL, I don’t know what is - you start to see the other kind, the ones who are just doing the work. They too show up in front of microphones, sometimes carrying a banner, but often just in the back, another body in a big or small group of bodies, experiencing the joy in community. And more often, putting stamps on envelopes or making phone calls or figuring out how to make a budget pencil out, finding the joy in the work.

Don’t confuse, as my high-school philosophy teacher once told us, happiness with having a good time. It’s a slog. After 15 years of applying for funding from the Department of Cultural Affairs, I swore I would never look at their website again. For every productive conversation with people working in good faith to find solutions, there’s another - or ten - with someone hoping to make a career, or use you for their benefit, or just enjoying exasperating you with argument.

Apart from the mundane work, for many - for people braver than me, sitting in my little office typing - for those who are on the front lines, walking across a bridge at Selma or trying to bring religious services to people in Broadview, people encounter real danger, physical danger. They use the word “struggle” advisedly. Their example makes me more than hesitant to apply it to what I do.

Because they, these folks working to make a better world - working, not fighting, and they, but occasionally we - they go to bed tired, knowing they didn’t accomplish what they wanted or needed to, knowing that they will not in their lives accomplish what they need to. Knowing that the work will be there tomorrow,

And in moments of enlightenment - I’m going to use the word we here - we're ok with that. Because we want better outcomes, and just as a crowd of protesters is made up of a bunch of individuals who by themselves could demonstrate nothing, the fight for liberation is made up of a million single acts, a million stamps on envelopes, a million meetings and bake sales and yes, arrests and worse.

And they, or we, might not get there with you, as someone once said. At some point, you have to get ok with that, too.

I don’t know whether Zohran Mamdani is ok with that: he’s young; he’s prominent, especially for someone so young; he has actual power even if, as Nolan Hicks suggested, it comes with some seriously difficult constraints and frustrating opponents. He might think he can change the world. But my gut tells me, in the way his campaign was run, in the way he embraces his supporters, in the way he understands collective effort, and especially from the simple fact that he’s hung out with socialists and therefore has undoubtedly been to more meetings where less was accomplished than anyone ought to have to endure - my gut tells me he’s going into this new job knowing exactly what the work is going to be like, even if he doesn't know the specifics of the problems he’s going to encounter. And that he’s probably happy in many ways, no matter how much he enjoyed standing in front of a cheering throng on Election Night, to have the campaign and even the winning behind him, and to be able to get to work.

I think the best 208 weeks of his life lay ahead of him.