what we play about when we play

Toward the end of Virginia Heffernan’s fascinating essay, “The Very, Very Nice Robot,” about a Diplomacy-playing AI program called Cicero, she pivots - I am slightly spoiling Heffernan’s denouement here - to the question of what she calls “the metagame problem”:

The metagame of Diplomacy (or jackstraws, Scrabble, bowling, etc.) can be seen as its place in the world. Why play this game? Why here and why now? Is it a test of raw intelligence, social skills, physical prowess, aesthetic refinement, cunning? You might play Wordle, say, because your friends do, or it relaxes you, or it’s rumored to stave off aging. An AI that’s programmed to play Wordle just to win is playing a different metagame.

I have never played Diplomacy. Candidly, it sounds like a chore. I used to play Risk with my brother and I never enjoyed it all that much, and even less did I enjoy being beaten by him every time. At 58, I can’t imagine I have the patience to learn to be good enough at Diplomacy where it could be any fun at all, and even if I got to the point where it could be fun, I don’t think it would be fun.

That said: For the past two years or so, my sister and I have played three games together almost every morning: Wordle, which everyone knows; Worldle, in which you have six chances to guess the name of a country from looking at its silhouette; and Globle, in which you have, and occasionally need, unlimited guesses to identify a secret country based on its distance from other countries. Worldle adds some bonus rounds about population and size and so on if you guess correctly.

We’ve played long enough now to have been around the world several times, although it has not appreciably helped me remember the location of any given island nation in the Pacific Ocean.

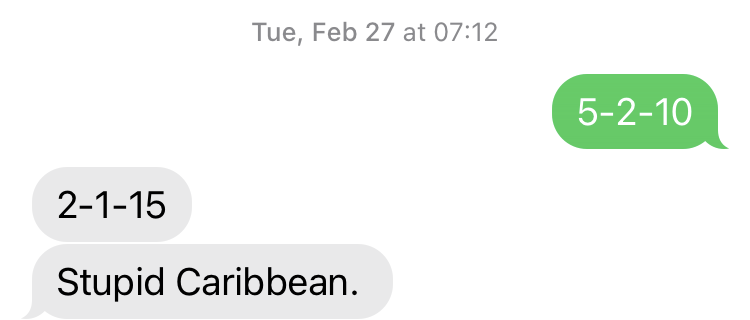

We have played these games “together.” We live in different states hundreds of miles apart. We play them, as the AI geeks would say, asynchronously. Sometimes I’ll forget and rush to play before bedtime. We have no particular rules between us, other than the understanding that you don’t spoil the other person’s play. Each day after playing, one of us will send the other a three-digit code, and sooner or later the other will respond in kind:

That’s, for me, a solid three-guess win in Wordle (CLONE), a shaky 5-guess success at Worldle (Uganda), and a middling 7 guesses to locate Mozambique in Globle. As you can see, Kathy succeeded better across the board.

From time to time I’ve thought about how long this morning ritual - walk the dog, heat the teakettle, make sure no buildings collapsed overnight, solve three puzzles - will continue. We’ve been around the world, what? Three times? Four? Surely that will get old. (Not as long as there are island nations as yet unswallowed by climate change, it seems, nor while I can have mental blocks that somehow cause me to forget Ghana, despite it being home to the most prolific dating-app scammers.)

But, you know, once something like this gets rolling, how do you decide to end it? Will we just become, out of boredom, less fastidious about it? Will something new come along? Will … ? And that’s where I stop pondering and get on with putting down a pee pad for the dog.

But because I stop pondering there, I’ve never until now gotten to Heffernan’s question, which - if I had been willing to continue my musings - I would have realized is the real question: What’s (as the geeks put it) the metagame? Or, as my therapist would put it, What are you getting out of this?

OK.

One: Most simply, a connection. A human connection. A sort of human connection. It’s intermediated, of course; we’re not together while we’re playing together. We’re not even talking. Even when we’re home at the holidays, and playing, we sit in our separate chairs looking at our separate phones, and still text each other the results! (That last bit might be my fault.) And yet, thanks to this intermediation, every day between us, we are able to send a message: I’m here. Are you there?

Sometimes that’s all it is. A ping; a ping back. But of course, sometimes there’s more. What are you doing today? How’s the new boss? Did you get the new car yet? Did you know Qatar has more than seven times as many expats as citizens?

Two: Knowledge. Not in the obvious way. With Wordle, for example, it’s a pretty rare word that I can’t recognize. Even if COPSE shows up, I’ll be ready for it. But I might look up (and share) an etymology. And with the geography games, untold questions arise far beyond where nations are. Like the number of migrants in Qatar. Or, What is West Sahara? (which Worldle recognizes but Globle does not). Why is Suriname independent but French Guiana is not? Why is the main language of Equatorial Guinea Spanish, yet its currency is the Franc?

That last exchange led to some fairly rare - at least until now - metadiscourse between us:

Three: I am thinking now - I have no better transition than that, but it seems relevant - about the way shared private languages develop without our guiding them. Suddenly we have our own words for things, or begin using a phrase, totally out of context, that has meaning to us and would be incomprehensible to anyone watching - in the same way that, when technologists have set two AI machines into a conversation, within hours the computers communicate with each other in language that is completely indecipherable. Or we develop jokes that are reduced to two words. How vital is this shorthand in a relationship; how it reminds us, each time, of the depth of our connection. How hard it is to develop your secret code when you’re far apart.

Four: Heffernan’s question Is it a test of raw intelligence? echoes another question I’ve had over the past months of circumnavigation: are we competing with each other? My answer is a resounding 🤷🏼♂️.

I think - Kathy will read this and it will spur further metadiscourse - a tacit agreement that this isn’t competition. Or it is competition. Or it’s competition but in a friendly way. The “winner” certainly never gloats; tomorrow either one of us might have a moment of stupidity or guess a combination of letters that leaves us with something like S_ORT, which might be SHORT, or SNORT, or SPORT, or depending on the depth of Wordle’s dictionary SKORT, and we’ll have to report the humiliating “bust.” And it is humiliating, just as a score of “2” is exhilarating.

I think - Kathy will read and agree, or not - it’s more a case of partnership in battling a common foe, whether the foe be a game editor who believes INTRO to be a standalone word, or the memory-defying arrangement of the Windward Islands. At the end of our brief exchange, sometimes explicitly and sometimes privately, we congratulate the other and resolve to do better the next time. Some days you get the Balkans; some days, the Balkans get you.

Finally, mostly: What we get out of this ritual is a ritual. This deserves its own explanation, its own book probably (probably there are hundreds out there). But I will try this, for now, for me: It is one thing I do each day. I might not get to my latest writing project. I may have a bowl of cereal for dinner. I may wake up and read that a ship has run into a bridge and no one knows why. But in the tiniest of ways, I had a thing to do, and then I did it; it was undone, and then it was done. The moment of satisfaction is, perhaps, a tiny reminder of the bliss that comes from chop wood, carry water.

“This ritual is a ritual” is as tautological as tautological gets, the sort of thing that causes a computer to spin in an infinite loop. And so, perhaps, with us: We play not to win, but to keep the game going.

Thanks for reading notes for nobody but myself! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

This post is public so feel free to share it.