you had to be there

In the theater, sometimes everything comes together and the result defies gravity. But you have to be there to see it happen.

As you may have gathered, I'm working on a book about what I learned in 25 years of producing theater in New York City, most of that in an out-of-the-way, primarily low-income neighborhood in Brooklyn. I didn't realize I was writing a book until I got a few posts into it. That's how life goes sometimes.

The posts here that I'm thinking of as chapters in the book are a bit longer, so I'm breaking them up to make them a bit easier to consume. It may be that you'll hate this - please let me know, and I can go back to keeping everything together for the next chapter. Anyway, this is Part 1 of 3.

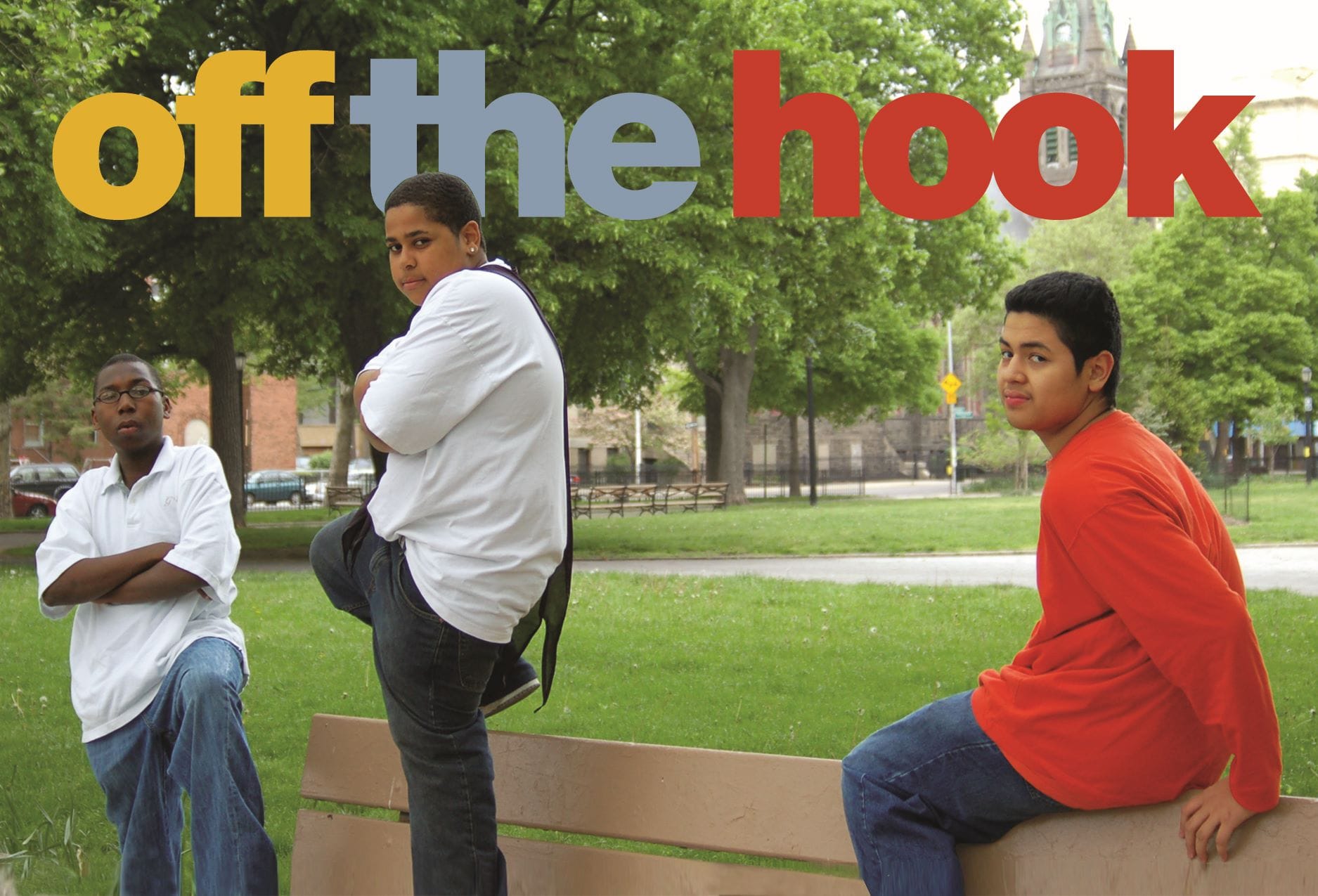

My favorite production in 18 years of Off the Hook was one I never saw.

Of the ones I saw, my favorite was probably an early one that three boys as playwrights. (They’re all my favorite, of course, but I remember this one especially.) One of the boys, Kareem, was a returning Off the Hook participant. In the very first iteration of the program, before it even was a “program,” Kareem had starred in a fantasia he wrote about a young man named Lee who ran away from home with a giant suitcase and camped out in an abandoned subway tunnel, where he encountered ghosts and homeless people. His second Off the Hook play was a sequel titled “Lee in Area 51.”

The second young man, Andre, came to us through our partners in the afterschool program at our local school. Andre had grown up in the housing projects, and his play was a commonplace but revealing domestic drama about family life. Like a lot of the kids’ plays, I suspect it was really about some other conflict that Andre wasn’t ready to engage, and with his play he was really practicing how family conflict might play out. We would see that in almost every iteration of Off the Hook. A young person would have some personal issue they wanted to grapple with, but in the writing they would realize that their parents and friends would be in the audience. The bolder ones might tackle the problem head-on. More frequently, they would invent some sort of allegorical conflict involving a character whose name was one letter off from their own: “Molly” instead of “Holly.”

The third kid, Jacob, was referred to us by a friend who volunteered from time to time and thought it would bring him out of his shell. It did, and he brought out along with himself an amazing, over-the-top mid-century Hollywood blockbuster that echoed Sunset Boulevard. To say the least, it was astonishing to sit down with a Latino boy from Red Hook, transcribing as 1940s melodrama poured out of him.

The three had next to nothing in common. I don’t especially remember whether they bonded personally, but they bonded in their committed approach to making theater. They each wrote full, if short, plays; they learned their lines; they showed up for rehearsal and participated in “loud and clear” practice.

I suppose it was my near-favorite in part because Off the Hook was so new; we had only done three or four iterations of the program. We could still fill a 200-seat auditorium with the only form of theater our Red Hook neighborhood had to offer, and having an audience always helps. We also had some exceptional actors and directors for that show, ones who took the time to understand the playwrights’ visions for their plays and to be as faithful to them as possible. In the end it all worked. That’s one of the beauties of the theater: Sometimes everything comes together and the result defies gravity.

I could tell you about everything that happened in those plays - but I’m getting ahead of myself.

My favorite Off the Hook, as I noted, was one I didn’t see. There were probably four or five playwrights in this one. I can’t really remember any of the young people but a boy named Adrian (although I think one was a lovely and shy young woman who was terrified of being onstage, which was funny, or telling, because she wrote a Wizard of Oz type story about a farm girl who is whisked off to Hollywood and becomes a star).

Whatever they were about, I’m sure the others were fine.

Adrian’s play, the one I want to tell you about, was a play about a family of chocolate people who went to find their creator, a chocolate maker. The number of possible allegories and allusions in just that sentence is remarkable. I don’t remember the full of the plot, just that they started at home, and they were for some reason dissatisfied with their chocolate existence, and they went off to demand answers. The chocolate maker lived in a well-fortified castle - because, of course he did - and most of the play was about their perilous journey.

Eventually, they reached the chocolate maker’s castle, and found him, and made their demands for information. And he answered them in a way that revealed to them their lives’ purpose. And satisfied, they went on their way.

Once again, you could say The Wizard of Oz laid out the basic framework of the plot, but it would be more correct to say The Wizard of Oz, like many Off the Hook plays, tapped into the foundational human archetype story structure that Joseph Campbell spelled out in The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Anyway, the plot is not the point. The production is.

The first thing you need to know is that Adrian was an African-American boy from Red Hook. He was small, he smiled constantly, he delighted in being able to do things. Adrian had grown up in the Red Hook Houses, the largest public housing project in Brooklyn. Our office space was also in that housing project, which sat across the street from the school where we produced the kids’ plays.

A second thing you need to know is that, in general, for Off the Hook we pursued everything-blind casting. Not just race-blind, but age-blind, physique-blind, gender-blind: Anybody could play anybody.

Part of a producer’s job, which was my job, is to think about what will go wrong, and a play about a chocolate family featuring a young Black man and adults who were not Black immediately presented any number of ways things might go wrong.

And third, you need to know that in addition to a policy of everything-blind casting, we had a policy of practicality-blind playwriting. You want time machines, laser battles, flying cars, all on our tech budget of twelve cents? We’ll figure it out. Relying on volunteers, some of them highly trained actors and some of them community members who hadn’t been on a stage since playing a tree in the second grade, meant that we had to work around stage combat. (Slow-motion acting is an excellent device for such instances.) A car could be four chairs facing the audience and a mimed steering wheel, or a masonite silhouette with handles on the back so the actors could carry it, or two actors crouching and going “brum-brum-brum” as they stepped across the stage.

Phones were actual phones, or foamkore cutouts, or hands, or nothing. A tsunami of dancing poop was - well, just understand that at one point a young woman wrote a play in which a character dreamed her bed was submerging in a flood of sewage, and our job was to stage it as faithfully as we could.

So, a chocolate family trekking through the wilds of a fantasy world to assault the castle of the chocolate maker and battle his armies?

Scene One (to Adrian): This is an amazing play. We got this.

Scene Two (amongst ourselves): How exactly do we got this?

Inevitably, the answer: We’re going to find the most talented artists you know, who have the sensitivity to understand the fullness of the task and the genius to communicate this vision without being literal.

I had a professor in a Shakespeare class in college whose brilliance was that he wasn’t a Shakespeare expert. He was a poet. We were forging our way ahead together, through terrain unfamiliar to all of us, but with Terry as our expert in navigation. Throughout the term he wrote us “epistles” regarding ideas he was finding interesting. The first of them - it was literally titled “Epistle The First” - posited an hypothesis1:

An hypothesis: serious writers past and present emphasize those things which they believe are most fundamentally real.

And he added two corollaries:

Corollary 1: The real is impossible to define, though we all intuit its nature.

Corollary 2: Art is powerful when it touches those intuitions.

With the benefit of all this time, I would add a third corollary, which may be so obvious that Terry didn’t feel the need to write it down:

The people we call Artists are those among us capable of creating work that enables us to recognize the real.

Even if - maybe especially if - that sense remains an intuition, a feeling that we cannot put into thought or words.2

So while Falconworks may have practiced everything-blind casting in every definable respect, we also - and here I mostly mean our artistic director, Pink - were keenly attuned to one, more important, question: Of everyone we know, what artists are best suited to comprehend this work and honor it properly and translate it from the page to stage. To recognize the real, and discover how to communicate its essence, indirectly.

The beauty of theater is that it is a collaborative work. That may be the dumbest, most obvious and simplistic sentence I have ever written. (And yet, some playwrights don’t understand this; they’ll complain, even sue, about interpretations that they think do violence to the original intent of their scripts. To which I say, “Then you should have written a novel, fool.”) When I would mentor an Off the Hook playwright, I would make a point of saying, “If there’s something you want to have happen onstage, you have to put it in the script somewhere, because there’s going to be a director and a bunch of actors and they’re going to take your work and do whatever they want with it.”3

But our job, as producers, was to make sure we were finding people who would, as I said, honor the work, stage it faithfully. I’ve used that word “honor” twice now. To create the kid’s vision in flesh and blood, and sometimes masonite. It’s easy to not do that. It’s easy, if you’re running a kids’ theater program, to think it’s about you, or a style of work that your audience expects, or something other than what the kid wants to create. In the playwriting process you can insist on a well-made play, or you can tell a kid “we can’t have a helicopter onstage.” Or even ask, “How do you think we can create a time machine?” (That’s not the playwright’s job - they’re writing the play!)

Or worse, you can take a script, the child of a child, and in some way mock it or wink at it or ignore a stage direction or re-write a line because you thought it wasn’t clear. To substitute your own intuition of the real for someone else’s. And that’s how you strangle creativity in the womb.

Continue to Part 2 of you had to be there here.

Terry was the one who used “an”; I’m way too Midwestern to roll that way. But we were in England, and I suppose that was the local dialect. ↩

All of this sort of dances around the question of what we are talking about when we talk about “art.” Or, “Art.” Hammett’s definition is: “A work (a performance, a piece of writing, a piece of music, visual art, an experience, etc.) in which the audience participates in constructing meaning.” The more the audience participates, the more a work is art. It exists on a spectrum.

Obviously we could argue about this for, oh, about 10,000 years and counting. ↩

Working with kids, I kept my language clean. But I once went to a seminar by the design guru Edward Tufte, who phrased it, “You have to jealously guard your work against the army of others who will try to fuck it over.” Ideally, theater is a little more collaborative than that scenario. ↩