you had to be there (part 2)

The theater is where we choose to believe. But you have to be there to do so.

This is the second part of a three-part post on making theater. If you missed it or want to remember where I left things, Part 1 is here.

When I left off, I was talking about the importance of honoring our young playwrights' works.

So: It was our job to make sure we had artists who could honor the work and stage it faithfully. We worked with directors who could do wonders staging that kitchen-sink drama - of which, as I noted, kids wrote many - but whom you wouldn’t want to task with a play about zombies. And we knew directors who would thrive in fantasyland but be bored with - and maybe as a result do violence to - that domestic drama.

Adrian’s director was Peter Born. Peter is an insanely talented director, a visionary, an artist in the true sense of the word - in my true sense of the word, anyway - someone who could intuit the real and communicate it. We had no business, our tiny, just-kind-of-working-with-kids-over-here-in-end-of-the-world-Brooklyn theater company, being able to draw on talent like Peter brought to the table. Except, we had an extremely gifted artistic director, who also had the academic credentials to back it up, and connections that came with those academic credentials. More importantly, we did our work honestly and seriously, and that attracts true artists.

You know, the kids would write these simple plays. Maybe ten, maybe fifteen pages long. Mostly telling familiar stories, some of them Wizard of Oz fantasies, some of them gangster showdowns, a lot of them involving a relationship crisis or bullying at school or parent-child struggles. Occasionally a play involving a talking cat who solved a murder or a kid who meets ghosts in the subway, but even those tended to come back to adventuring out into the world and wanting nothing more than to find one’s way back home. The way Dorothy did. The way we all do.

The kids would write these simple plays. And yet, underneath those fifteen pages would be every conflict, every emotion, every desire and fear that any of us have ever had. And because we were blessed with talented artists, partly because of the way we worked and partly because of connections and partly because in New York City, as difficult as it can be to produce theater, one benefits from an embarrassment of theater riches - because we were blessed with these artists, and we took the work honestly and seriously, the directors and actors who joined us were able to mine the truth - the “real” - out of those simple plays, to reveal the depth of emotions that the young people might not even have been cognizant that they were writing about. And so we all could share it with our community, our audiences, our friends and families.

(It would be easy - maybe I’ve said this before - it would be easy to look at what we did and say that we were working with extraordinary kids. Nothing could be farther from the truth. We had Adrian and Kareem and Andre and that lovely shy girl who dreamed of going to Hollywood. Wonderful kids, don’t get me wrong. But ordinary in their wonderfulness, or maybe wonderful in their ordinariness. Wonderful the way all kids are wonderful. They all carried within them the same range of feeling any of us do, and the same need to express it. We just gave them an opportunity.

Some of them had fairly profound learning disabilities; couldn’t reliably remember a single line that they themselves had written, would take hours to write three sentences, had no focus whatsoever. If you want to know what I am most proud of in the work we did, my answer would be, is: We never turned away a young person because of ability.

The good stuff is always in the footnotes and the parentheticals, by the way. Just sayin’.4)

So: Adrian’s director was Peter, and Peter faced the question of how to represent a perilous trek through the forest and a paramilitary assault on a chocolate maker’s castle. As well as the question of how to do so with a group of white-as-the-driven-snow actors and one Black child, representing onstage a chocolate family. I distinctly remember running through, in my mind, the number of ways that might have gone wrong, and saying something about it. Pink calmly assured me that figuring that out was why Peter was there.

The solutions to both problems were ingenious, and totally theatrical, and completely different - yet united in their simplicity.

Chocolate, Peter reasoned, comes in a wrapper. It’s wrapped in foil. And so, at the beginning of the play, lights came up on a group of four actors encased in aluminum foil, slowly undressing themselves to reveal the people underneath. It was nothing, it was utterly obvious - so obvious it took talent to see it. And having seen it, to make the most theatrical choice: the unwrapping. I suppose a more conventional approach would have been making four costumes that looked like candy wrappers, red and black with yellow lettering reading “BROOKLYN CHOCOLATE COMPANY.” Peter knew that the better choice, the more thrilling and wonderful (“wonder-full”) choice would be for the family to reveal themselves.

(And, incidentally, to allow the actors not to be confined by boxy, unflattering costumes for the entire play. And also, not incidentally for a tiny, end-of-the-world theater company, not require our non-existent costume shop to turn around four custom costumes in a week.)

So that was one.

The solution to dramatizing the chocolate family’s odyssey was both simpler and more genius. On a twelve-by-sixteen foot stage in an elementary school, how do you depict a perilous forest full of unknown dangers like wolves ready to devour a chocolate child? How do you show the looming height of the castle wall? How do you fill the audience with terror at volley after volley of arrows aimed at our heroes?

Peter wheeled in an overhead projector and proceeded to throw on a screen a series of simple, hand-drawn pictures.

How I wish I had those pictures to show you now. There was nothing to them. They were drawn with black marker on clear transparencies. The arrows were - you know, arrows like a kid draws them, two short lines making the point, a long shaft, a bunch of short strokes indicating feathers. Motion lines, like Keith Haring would put in his paintings. The merest indication of a flight of arrows.

I wish I could show you. You had to be there.

And I wish I could tell you how I reacted when I saw the show, with all of its unspecial special effects, in front of a full house. But I was working the box office that evening, and stood outside the school auditorium in the lobby while the plays ran.

I had to be there, too.

Rather than seeing the performance, I saw an audience emerge from the auditorium at the Patrick F. Daly School. Red Hook was famously a small town within New York City, so I knew a lot of the folks who had come out. Mostly I remember one of them, my friend Katie, walking through the red doors, wide-eyed.

“That. Was. Amazing,” she said. “I just watched an entire room of people believe that they were watching a chocolate family fight their way into a castle with arrows raining down on them. Every person in that room absolutely believed it.”

I still feel the pain of of hearing that and knowing that that moment would never be recaptured. I snuck in to watch the second performance the next day, but the peril of a siege of arrows is nothing compared to the peril of using antiquated technology in live theater. The overhead projector broke. They did the play without the special effects. The spell was broken.

People would say to us often, are you videotaping these plays? Will we be able to see them later? The answer would be some shrugging and mostly disingenuous mumbling about not wanting the video to be misused in some way, and that the volunteer actors - many of them professionals, occasionally someone recognizable - hadn’t agreed to that. All of which was true enough, but never really the reason.

The real answer was, watching a recording of the plays would be like experiencing a song by having someone tell you the notes. Sure, you get the idea …

It’s enough to say that theater is ephemeral. It’s enough to say that part of the joy of theater - like part of the joy of everything in life, maybe, if you’re wise enough to find it - is that it’s there and it’s gone. I do think performing artists, and their hangers-on like me, learn to appreciate life’s fleeting moments a bit more because we’ve repeatedly been made aware that on Sunday the set will be struck and the only thing remaining will be a bare bulb at center stage.

It’s enough to say that, but that isn’t everything.

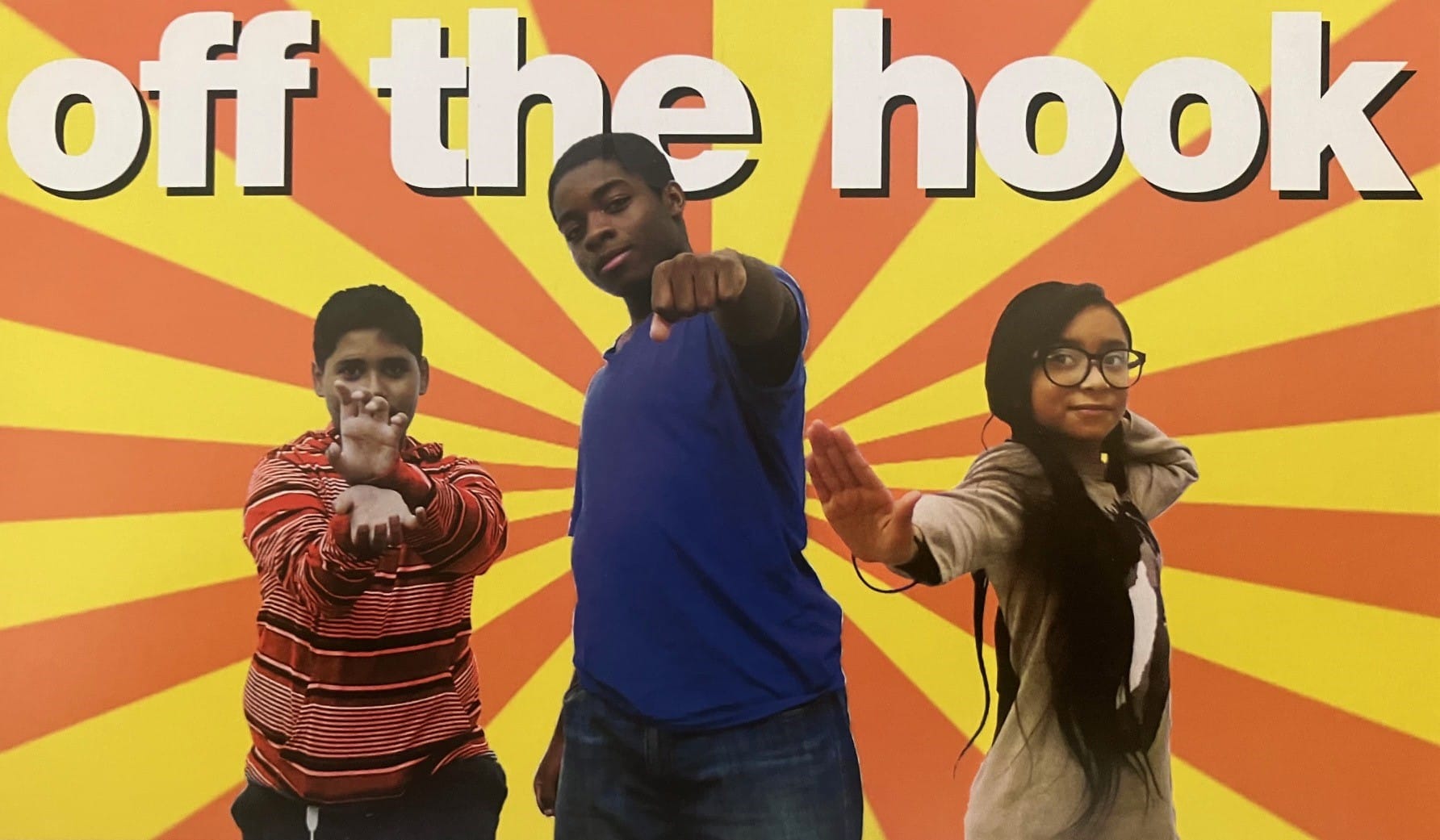

I think you had to be there because everyone was there. I used to write in grant applications about how one of the key contributions Falconworks made to our community was to bring together a hundred or more people to share an experience. That’s increasingly rare, even more rare than it was ten or fifteen years ago when I started writing that phrase. We don’t go to movies much anymore, we sit on the train - if we ride the train - staring at our separate phones; we - eh, you know all the examples. Our Off the Hook shows - all our shows, I would hope, but especially the kids’ shows - brought together a group of people with nothing in common. The Patrick F. Daly School, as I mentioned above, sat across the street from a public housing complex, but across the street in the other direction was a diverse, artsy, partly gentrified, isolated neighborhood of folks who had chosen to live in that spot despite its disadvantages. Some of them came to the plays because they were our friends. Some of them showed up because the kids were their friends or family, but for the majority that wasn’t the case; they’d never heard of these kids before. Some of them came for inspiration, or to support the yutes. Some came to laugh at malapropisms, at absurd lines like “How many times have I told you to stop prostituting in the house?” or at ridiculous dei ex machinae. (The laughter was always filled with love.)

Some of them came to our shows because there was, famously, nothing else to do in the small town of Red Hook.

They came for whatever reasons they had, and they found themselves believing in a chocolate family battling for their lives against a storm of hand-drawn arrows.

And - I think this is the critical point - they suspended their disbelief - we can suspend our disbelief - because we have all chosen to do so. Maybe that’s not perfectly true, but there’s no question that being surrounded by others choosing to believe makes the job easier.5 And part of the genius of Peter’s hand-drawn transparencies - of making, in a way, the least possible effort to be “realistic” - was that it made the audience’s job clear: You have to make this choice. I’m not going to try to fool you into thinking that something impossible is happening. You have to decide to do that for yourself.

Continue to Part 3 of you had to be there here.

(I'm struggling with footnotes in the Ghost platform. Thanks for your patience while I figure it out.)

(4) You may not be aware that the world had entirely forgotten who been responsible for the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. Historians pinned it on a completely different emperor, Septimus Severus, until 1840, when a Northumbrian clergyman named John Hodgson wrote volume three of an exhaustive (in all senses, one presumes) history of Northumbria. In the course of writing this, he uncovered, literally, mounds of evidence pointing to Hadrian. It didn’t quite fit in his otherwise forgettable history, though, so he put it in a footnote.

(5) Of course, there’s a profound danger to this tendency among us humans; it’s the mentality of the mob. As a character in another show we staged, Pink’s Temporary Insanities, said, “People in crowds stop behaving like people and start behaving like … crowds.” ↩