you had to be there (part 3)

When it works, theater puts audience and actors not just in the same room, but together in the imagined world.

This is the final part of a three-part post on making theater.

Part 1 is here, and Part 2 is here.

We were talking about the audience's willingness - or obligation - to suspend disbelief...

If you spend enough time with the finances of theater, the absurdity of the enterprise becomes readily apparent. An actor in one of our mainstage productions once asked me, “What will you do with the profits from the show? Will the cast get any of that?” and I recall laughing in his face. I guess there are Broadway shows that turn a profit(6), but even in their thousand-seat houses, it’s a risky bet. And for a little theater company doing shows in an elementary school or on a boat or at a derelict grain terminal? I would look at our expenses compared to the number of people in the seats and think: there’s no way this makes sense.

I guess I didn’t really believe that; I kept producing shows for 25 years. I still wonder about it, though. What is it about theater that justifies all of the effort and all of the expense, for a few hundred people to come in and watch, only for it all to be washed away afterward?

I think it is this:

Theater is a place where we collectively decide things. More than any other art. More than almost any other forum, maybe with the exception of the good old-fashioned New England town meeting, which doesn’t happen in that way many places, and isn’t even possible for most people. And more to the point, which we don’t have any practice in doing.

I don’t know if we knew that when we were starting out. Maybe Pink had an inkling of it, she was always five steps ahead of me in such things. At first, I was just along for the ride. But our initial plays, regardless of how inventive the plots or the dramatic structure or staging might have been, basically consisted of: Audience here, Actors there.7

Over time, that became less and less true. We started incorporating Theater of the Oppressed techniques, which invited the audience to climb onstage and change the plays. We started breaking the fourth wall more and more, arriving at the point where it now feels like that fourth wall should never have existed in the first place. Our audiences started playing a literal role called “the audience.”

We handed them lines in one show; had a kind of communion in the next; called on two volunteers to be married; asked everyone to use their phones to research slavery legislation in Virginia. In Black Conference, our audience attended a conference about economic cooperatives in the 1930s. In The Program, they attended a 12-step meeting to overcome racism.

There were opportunities to learn what the kids today call “content” in each of these shows, whether the process of post-disaster gentrification, the origins of the concept of race, or W.E.B. Dubois’s theories of economic development. The trick was, what we were really teaching was the practice of engagement.

It takes nerve to raise your hand to participate in a game show with questions about colonial practices. It’s one thing to watch an actor read the oath that immigrants take when they become citizens; it’s another thing to say, in front of your friends and neighbors, the words:

I hereby declare … that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law …

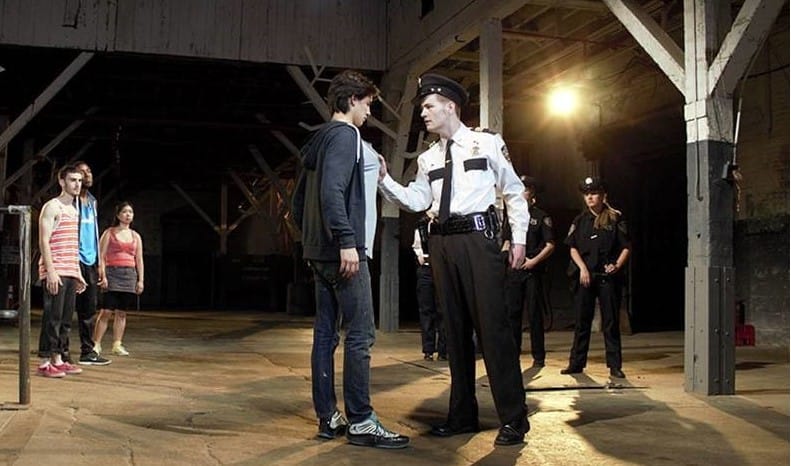

In the young playwrights’ plays in “Off the Hook,” we began practicing a Theater of the Oppressed technique called Forum Theater, which leaves plays unresolved, or resolved unsatisfactorily. Pink or another person in the role of the “Joker” would ask the audience, “Where is an opportunity to change the outcome of this conflict?” and the audience member brave enough to respond would be pulled onstage to replace a character and turn the scene in another direction.

The outcome of the play itself was immaterial. What mattered was the practice of raising one’s hand to say “this is wrong,” and of taking action to turn things better, to experiment, to put oneself in the role of a child and rehearse seeing the world from their perspective.

Someone once told me about a teacher who called theater “one group pretending to be people they’re not, and another group pretending to believe them.” That’s cute, but in the case of the best theater, the theater that really grabs us by the lapels - or by the heart directly - neither one of those groups is pretending. The actors are so deep in their roles that, for a moment at least, they forget that they’re acting. And the audience is so deep in its role - and it is a role - that it forgets that it’s an audience. They just absolutely believe.

In some ways, we were blessed by having audiences who didn’t go to theater that much. The more you see of any art - this is especially a challenge for critics, which at times describes me - the more you see of movies or theater or paintings or whatever, the more you tend to be distracted by technique and lose your connection to story. This is the challenge of living in the age of electronic media. We have seen so many stories, so many that the challenge for a creator is to make anything seem new. How many plays did even an avid theater-goer see in Shakespeare’s day? A few dozen? How many episodes of television did you watch in the last year?

That was true of Falconworks’ audiences, of course; they watched television the same way all of us do. But the immediacy of theater - actual live performers in the same room - broke down expectations, to the point that at times it was the audience who would tear down the fourth wall. “Don’t go with him!” they shouted at an actor playing young person being approached by an unsavory adult. Once when I was ushering, a man entered mid-play and saw characters facing a judge. “Oh, they had to go to court?!” he exclaimed, displaying no ironic distance, no suggestion that he was seeing a play - in fact, walking into the middle of a play. It made no difference to the urgency of the moment.

And of course - this is a truism about the theater - the audience would tell us, the company, things we didn’t know. They would laugh where we weren’t expecting a laugh, even where a laugh seemed inappropriate. And sometimes, you would learn to hold there - in the case of a ham (and god bless the hams who came to work with us) to milk the laughs.

But at other times, the reaction of our audience would remind us of what we were taking for granted, or uncover meanings that we hadn’t realized were waiting to be discovered. At a talkback after our mainstage production of Romeo and Juliet, one spactator said, “I watched this play and all I could think was, where are the grown-ups?” It’s not really the academic response to R&J, which is more likely to focus on poetry, the relevance of Queen Mab or the cleverness of “’tis not so deep as a well nor so wide as a church-door.” In the flesh, ten feet away, without that mental distance, you might consider that at that moment, and for no good reason, a young person is dying.

About the favorite plays I did see, that I mentioned back at the outset: Jacob’s play, in particular, started with Hollywood-style narration before flashing back to the start of the drama. From my lighting table on opening night, I looked around at an audience of about 150 people. Jacob came out in front of the curtain in a trenchcoat and homburg, and announced, in the most stentorian voice a middle-schooler has ever mustered, “I only knew her from the movies - but I never really knew her.”

Jacob was, as I mentioned earlier, one of the most shy kids we ever worked with. As he emerged from backstage I suddenly realized, “This is going to get a laugh, and he might shatter into a million pieces when that happens.”

It did, in fact, get one of the most full-throated laughs I’ve ever heard. And Jacob stood there and stayed in character, and waited calmly until the audience were ready for him to carry on. We ate out of the palm of his hand from that point forward.

How I wish I could return to that moment of exquisite angst, and then relief and delight. How I wish I could describe it to you in a way that you would understand, that you would feel it with me.

(6) Possibly not as reported to the tax man, but accounting and actual dollars are sometimes distant cousins. ↩

(7) Or maybe, Actors here, Audience there. The difference is more important than you might think: from whose perspective are we looking?